Hampton Court Green

Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation area no.11

Hampton Court Green

Contents

Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principal aims of Conservation Area Appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications.

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area.

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

It is important to note that no Appraisal can be completely comprehensive, and the omission of a particular building, feature, or open space, should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications and as an evidence base for the Local Plan.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance.’ The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to the national policies outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), the adopted London Plan policies, and the conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan.). Our overarching duty, set out in the Act, is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

Buildings of Townscape Merit

Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) are buildings, groups of buildings, or structures of historic or architectural interest, which are locally listed due to their considerable local importance. The policy, as outlined in the Council’s Local Plan, sets out a presumption against the demolition of BTMs unless structural evidence has been submitted by the applicant, and independently verified at the cost of the applicant. Locally specific guidance on design and character is set out in the Council’s Buildings of Townscape Merit Supplementary Planning Document (2015) which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

Archaeological Priority Areas

An Archaeological Priority Area (APA) is an established location where there is strong known archaeological interest or a particular potential for future discoveries. The local plans for the London boroughs describe APAs. They provide guidance for putting national and local planning principles into practise so that archaeological interest is recognised and preserved.

Historic England updated the Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal for the London Borough of Richmond in March 2022: London Borough of Richmond Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

Designation and Adoption and Extension dates

Hampton Court Green Conservation Area was designated on the 14th January 1969.

It was subsequently extended on the 7th September 1982, and the 7th November 2005.

Following approval from the Environment, Sustainability, Culture and Sports Committee on 17th January 2023, a public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between 17th March and 28th April 2023.

This Appraisal was adopted on 20th November 2023

Map of Conservation Area

Statement of Significance

Summary of special architectural and historic interest of the Conservation Area.

The significance of Hampton Court Green is closely linked with Hampton Court Palace, with buildings in the area dating from the 17th and 18th centuries being excellent examples of their architectural style. Some houses have long front gardens, with a mixture of brick boundary walls, ornamental gates and excellent quality doorcases and fenestration.

Hampton Court Green is a historically significant settlement, with Roman origins; it is designated as an archaeological priority area.

The Green is an open space with a strong semi-rural character. It provides an important green setting, in conjunction with Hampton Court House, Bushy Park and Hampton Court Park. Unspoiled since the 18th century, it is the central connection between the palace and the village which lay outside the Palace walls. Astonishing views from the Green are obtained in all directions.

The development of the area around the perimeter of the Palace is cohesive, where the 18th century impacted more on its streetscape and presents a unified scale and form.

Even though changes to the area have responded to trends of the time; some features have been preserved from the Tudor period that enhance the relationship with the palace. As a result of its architectural significance, there is a particularly high number of Listed Buildings and Buildings of Townscape of Meri located within this single area.

Historic Development

The evolution of the historical development of the area, including archaeology and plot morphology, that contribute to its special character.

Roman and Saxon Period (AD 11 – 1066 AD)

The earliest known occupation is of Roman origin, based on the discovery of roman weapons on the bank of the Thames, close to the Conservation Area. There have also been archaeological finds in nearby Hampton Wick, although further research is needed in this area.

Hampton Court Green also presents solid evidence from the Saxon period, as there is known to be the existence of a manor belonging to Aelfgar, Earl of Mercia. Furthermore, the name Hampton is derived from the Saxon language, ‘’Hamnn’’ which means a bend in the river and ‘’ton’’ a fortified palace, referring to the Saxon manor and the river Thames.

11th - 14th centuries

After the Norman Conquest, King William I granted the land to Walter de St. Valerie. In 1217, the descendant of the Norman Lord was exiled from England, and the land was granted to a London merchant, Henry de St. Albans. The land was later bought by the Knights Hospitaller of St. John of Jerusalem in England. It was during that period that the place started to be referred as Hampton Court, circa 1399.

15th and 16th centuries

The areas relationship with the English monarchy came about after the loss of Richmond Palace in 1497 by a fire. In 1514, Thomas Wolsey, Archbishop of York, and Lord Chancellor of Henry VIII bought Hampton Court when it was a country house. Wolsey gradually expanded the site to a large palace. This resulted in an increased number of people living at the palace however, it was always short of water. Therefore, two springs were accessed, and a wooden pipe was constructed that ran alongside Hampton Court Road to the building. There is still one pipe which runs through the cellar of the King’s Arms Hotel. Wolsey invested significant sums of money into turning the country house into a grand palace and eventually Henry VIII took it for himself.

As part of the expansion of Wolsey’s former house by Henry VIII in 1529, small workshops for artisans were constructed outside the Palace, and temporary houses were set up on the Green.

17th century

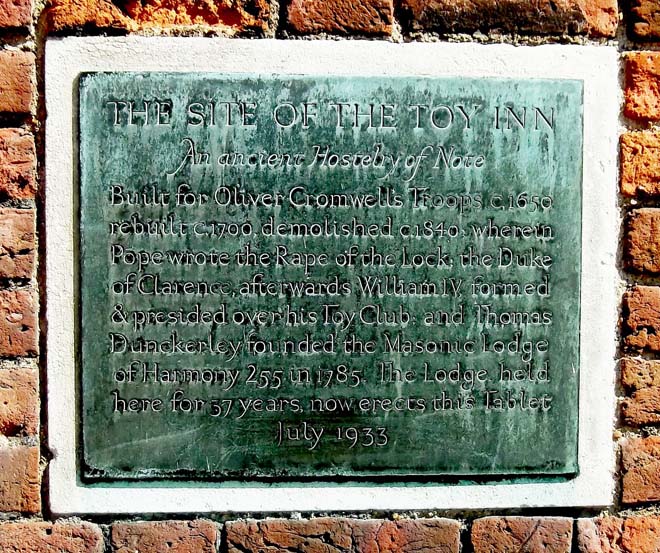

The Toy Inn, now lost, was one of the first houses to constructed to serve the workers of the Palace and sat outside its walls. After the restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, the Inn was granted to the Under Housekeeper. In 1697 it was rebuilt but demolished by 1840.

In 1785, Thomas Dunkerley founded The Masonic Lodge of Harmony within the New Toy Inn. A blue plaque has been installed where the building was originally located, as a reminder of its relevance for nearly 300 years due to the connection to the Palace and the village community.

Fig. 2 The Toy Inn, 1800. Museum of London

Near the Great Gate, several different service houses were constructed during this period to provide for the Palace, including a Bakehouse and Poultry Office. The Green, originally used as an arable field, became pastureland during the reign Henry VIII, used for cattle and horses, as well for archery practice. During the reign of Elizabeth I, a coach house was built as part of the Royal Mews, along with two new barns which forms an important intact survivor from this early period of the development of the area.

Fig. 3 Royal Mews illustration, 1865. Historic Royal Palaces

In 1636, for the first time in the history of Hampton Court, the Crown land where Ivy House now stands was granted to Nicholas Myles. Myles was Under Keeper of the House Park, and it was the starting point of different grants of land from the Monarch to workers of the Palace.

During the reign of King William and Queen Mary, the hay barn was converted into a stable, and a barn was erected in the Royal Mews.

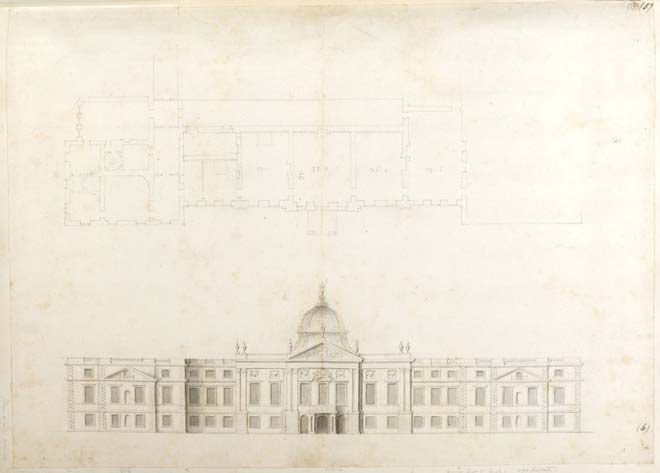

Sir Christopher Wren, one of Britain’s most notable architects, worked on the development of the south façade of Hampton Court Palace, and designed the Fountain Court. He also lived and worked nearby on Hampton Court Road. He lived in the Old Court House as Surveyor-General of the Crown and carried out alterations to the building. This house remains and a blue plaque has been installed on the front gate to commemorate Wren’s time at the property.

Fig. 4 Sir Christopher Wren Hampton Court Palace plan and sketch elevation for an entrance façade,1669. Sir John Soane’s Museum London

At this time, the Green was surrounded by craftsmen's houses, some temporary, but others developed into permanent buildings. The northwest side of Hampton Court Green had different stages of development. The first registered is from 1690, where two stables and a coach house were in the current Bushy Park south entrance. Houses between the walls to the Palace were located as well on the north side, five were located on the south side of the road, but only three remain along with Wilderness House which is situated inside the Palace walls.

At the end of the 17th century, granting land for the Palace service staff started to be accepted. The Under Housekeeper built Palace Gate, and the Royal Gardener built seven houses, coach houses, stables and two inns in the north-east of Hampton Court Road.

18th century

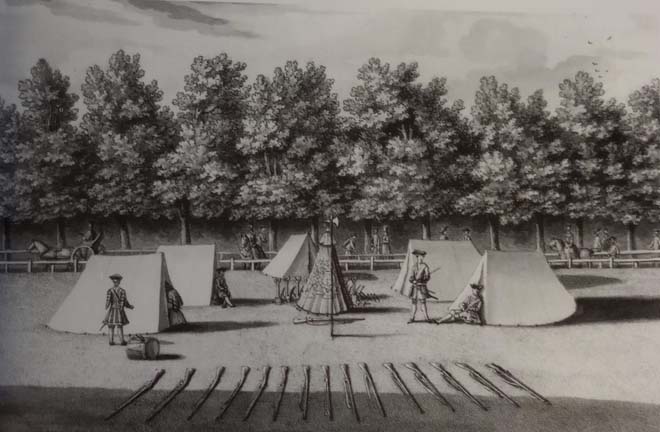

The Green was used as a camp for the military during George I and George II's reigns, and the sale of copyhold leases started to bring new owners to the area. In 1743, Prestbury House was built and in 1757, George Montagu, Earl of Halifax, built Hampton Court House.

Hampton Court House was designed by architect Thomas Wright for the mistress of the Earl, Anna Maria Donaldson. Wright also designed the garden which included a Shell Grotto.

During the 18th century, the works buildings in the Green were dismantled, and relocated around the palace walls. The plumbery was re-erected on the north-east side in 1700, where it is now located on Campbell Road. At the junction with Hampton Court Road, in the current location of Craven House, there was a refreshment house for the palace workers. The grocer and cheesemonger were located either side of this plot, and later these were converted into a confectioner’s shop and a servant’s registry office.

Fig. 5 An East View of the Quarter Guard on Hampton Court Green, Bernard Lens III,1773. Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

In 1785, the Cardinal Wolsey public house was built by David Feltham, the tollkeeper of the second Hampton Court bridge.

The King’s Arms had registers of its existence from 1658, where it was named Queen’s Arms and then Queen’s Head as a reference to Queen Anne. By 1736, however, it has been renamed King’s Arms. It was originally used as a house for two widowed sisters but later became a hostelry. By 1772 it was acquired and extended by a family of distillers from Hampton who bought the plot opposite the side of the road, to provide coaching services to the hotel.

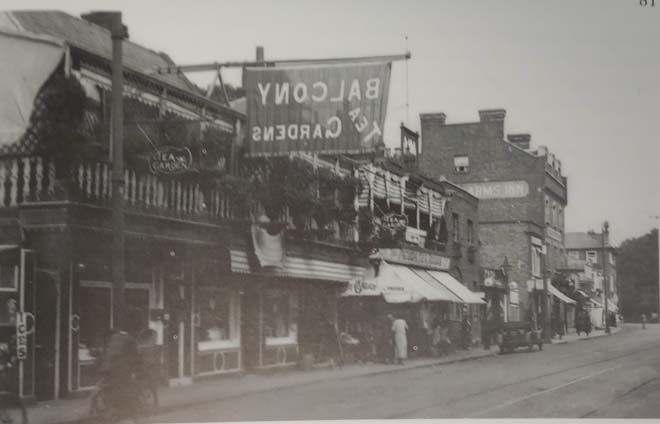

Fig. 6 Picture of the Palace opened to the public, 1909. Historic Royal Palaces

19th and 20th centuries

During the 19th century, many alterations began with the opening of the Palace to the public.

The Hampton Gate was abandoned in 1810, and the Green was no longer used as pasture field. By this time, it was more commonly used to hold fairs and festivals. Due to a dispute between neighbours, the Palace Gate was divided into two separate buildings.

In 1812, George III granted the rights for development in Hampton Court, as it was still owned by the Crown. However, he included a condition that the Green remain unspoiled to avoid any building being constructed in front of the palace and preserve its views. As a result, the Green has not altered since then, except for the car park on the northwest side.

Queen Victoria opened Hampton Court Palace to the public in 1838 resulting in many refreshment houses being established. The Greyhound Hotel was built in 1852 to provide services to visitors and currently forms part of The Lion Gate Mews Hotel. The cottages around the area became part of the commercial growth of the village. From the late 19th century, they were, at various times, tearooms, grocers, a restaurant and a bootmaker. The Palace Police occupied the Palace Gate House, and later this building became the village Post Office.

However, as visitor services started to become established within the Palace, this had an impact on the surrounding area with many shops subsequently closing. As found today, there are only few remaining shops to illustrate the historic commercial character of the area with the predominant use now being residential.

The village started to be modernised in the mid 18th century and in 1853, streetlamps were installed and the first telephone exchange within the Post Office was opened in 1873. Hampton Court Road East was widened in 1900 to cater for the increase in traffic in the area.

Fig. 7 Hampton Court Road east, circa 1938. The Collection of John Shaef.

Michael Faraday, a well-recognised scientist, was granted by Albert, Prince Consort, a house (Faraday House, former master's Mason house) on Hampton Court Road.

After his death, the house was granted to three princesses, the daughters of Maharaja Duleep Singh. One of them, Sophia Duleep Singh, is known to have participated in the Women’s Suffrage campaign in 1906.

Fig. 8 S.Dhuleep Singh outside Hampton Court Palace, 1913. British Library

After the First World War, new residents moved into the vacant sites on Crown land. During the Second World War, only Rose Cottage suffered bomb-damage. In the 1980s new houses were built on the east side of the road and a Petrol station. With the exception of these changes, the area has much of its historic character and layout making it a highly significant historical area of the borough.

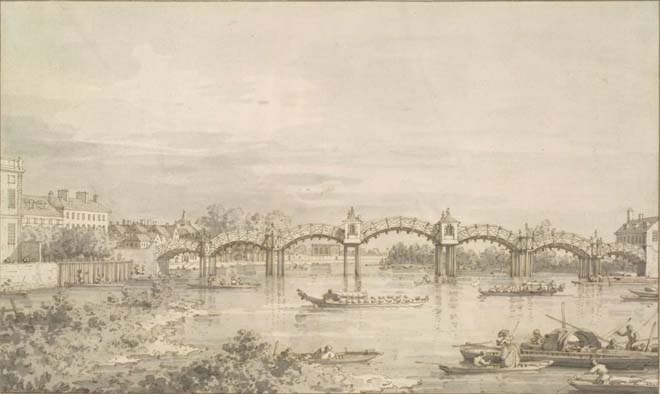

Hampton Court Bridge

On the south side of the Palace there was a ferry across the River Thames, however this was inconvenient for the court and in times inaccessible due to flooding. This led James Clarke to obtain rights to build a private bridge in 1750. This was constructed of seven wooden light arches and built in the Chinoiserie style but was demolished 25 years later. The second bridge of 1778 was also of wooden construction, in this case with eleven arches and stronger wood.

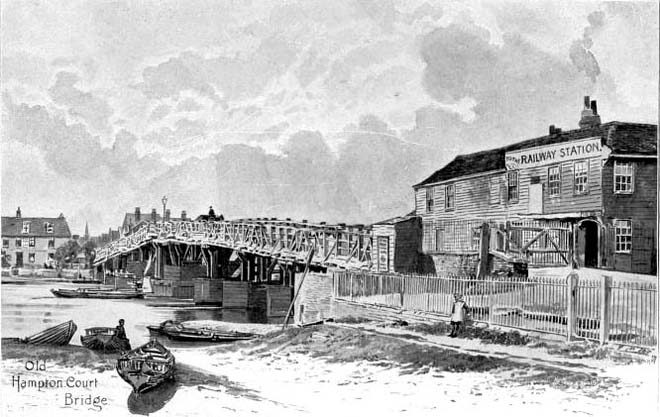

The third bridge was built in 1865; it consisted of wrought iron lattice girders resting on four cast iron columns. The wrought iron proved inadequate for the dense traffic on the bridge and the increasing use of motor cars, which resulted in the bridge being demolished in 1925.

The fourth and current bridge was built in 1933, with three wide arches, and was designed by Mr W.P Robinson with Sir Edwin Lutyens, as a red brick with Portland stone dressing structure.

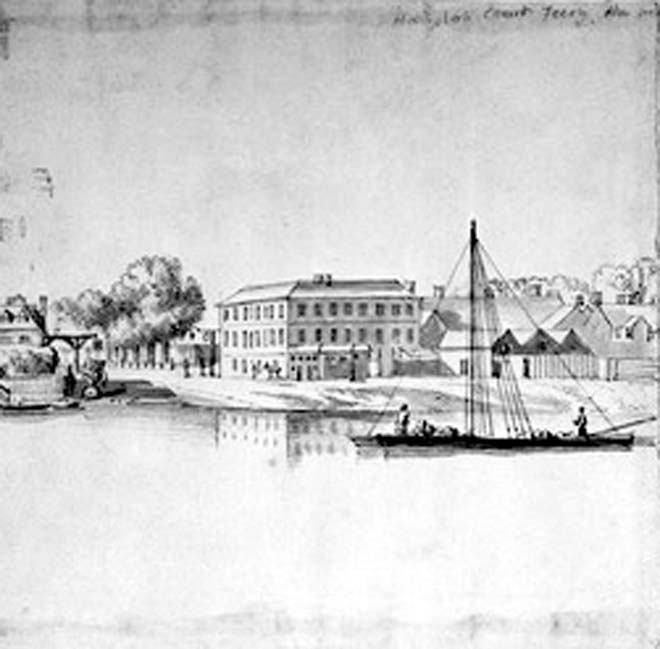

Fig. 9 Hampton Court Bridge, 1754. Drawn by Giovanni Antonio Canaletto.

Fig. 10 Hampton Court Bridge 1850. Thameside Molesey- Hampton Court Bridge Bushy Park

Bushy Park

Bushy Park, although forming its own Conservation Area, has a strong connection with Hampton Court Green. During Cardinal Wolsey's ownership of the Palace, the park was used as ploughed farmland. Henry VIII instead, decided to use the park as a deer park. During the reign of Charles I, the Arethusa fountain (Diana fountain) was installed to connect the lower levels of canals that flow from Longford River. Sir Christopher Wren designed the setting for the Arethusa fountain and expanded the plans to Chestnut Avenue.

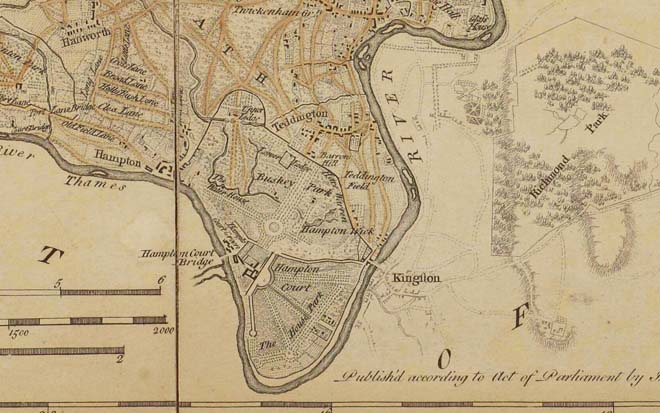

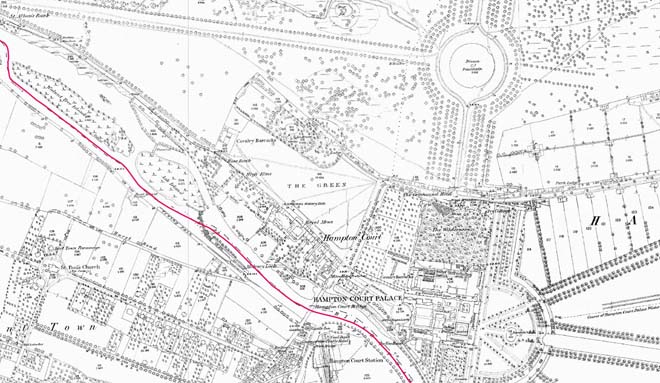

Historic Maps

Fig. 11 Extract of Hampton Court from 1757, Middlesex, map by Emanuel Bowen.

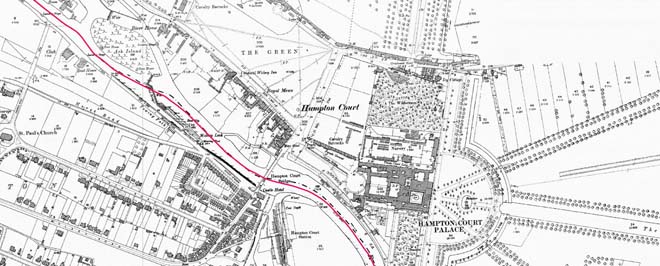

Fig. 12 1866 map, Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland

Fig. 13 1869 map, Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland

Fig. 14 1895 map, Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland

Fig. 15 1932 map, Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland

Fig. 16 1954 map, Ordnance Survey. National Library of Scotland

2. Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Boundary

Hampton Court Green Conservation Area is in the southwest of the London Borough of Richmond, enclosed by the Bushy Park Conservation Area (No. 61) in the north, Hampton Village Conservation Area (No. 12) in the west, Hampton Court Park Conservation Area (No. 60), and Hampton Wick Conservation Area (No. 18) in the east.

It is bounded to the north and west by Bushy Park, to the south by the River Thames, and the east by Hampton Court Palace, having the River Thames as its natural boundary to the south.

Fig. 17 Conservation Area Statement Map

Setting and Topography

Hampton Court lies on the north bank of the River Thames. The area around Hampton Court Palace was developed to accommodate additional functions and provide adjacent service buildings to the Palace. The setting has only been modestly changed since the 16th century, with some alterations to road layouts and construction of the bridge across the river.

The Hampton Court Green Conservation Area is divided by Hampton Court Road (A308), isolating the palace and its surroundings to the east. It is located between the southern end of Bushy Park and Hampton Court House.

The rear elevations of properties fronting the north side of Hampton Court Road East face directly on to Bushy Park and are mostly built into the park boundary wall, contributing to the setting of that Conservation Area. The rear of the dwellings at Hampton Court Road West faces the River Thames and have deep rear gardens running down to the riverbanks.

Topographically, the Conservation Area is flat with no notable inclines.

Fig. 18 Aerial photography 2021

Fig. 19 Aerial photo of Hampton Court Road east in 1948. Historic England.

Townscape

The layout of the Conservation Area is defined by Hampton Court Palace and the route of the A308. Hampton Court Road (A308), subdivided into east and west, creates two distinct characters. The east maintains all the architectural features of its relationship with Hampton Court Palace and Bushy Park. The west is dominated by the Green but also includes features that relate to the Palace, with development largely dating from the 18th century and featuring diversity of architectural styles.

The Green

The Green forms a substantial portion of wide-open space that forms the centrepiece of the area and which connects all the streets in the conservation area. There are also many undisturbed views across the space allowing appreciation of its highly historic surroundings. A row of trees lines the perimeter of the Green on the south side, creating a natural boundary confined only by a low wooden post and rail fence. As a result of the Crown removing any rights to develop on the Green, its character has remained largely unaltered since the 17th century, forming the foreground to all the buildings which address the Green and the Palace.

Fig. 20 The Green. View from Hampton Court Road east.

Hampton Court Road west

Hampton Court Road West is straight and wide, with residential buildings on the south side, and Hampton Court Green to the north. Most of the properties are three storeys high, creating a cohesive domestic scale which is enhanced by dormer windows and chimney stacks. A key element of the character is the front gardens with brick boundary walls, with a few exceptions being timber gates and black iron railings. The Royal Mews is the most dominant element in the streetscape, a late 16th century Tudor stable with later alterations and a clear divisor between the rows of Georgian houses on one side and 18th century cottages on the other side.

As one of the oldest buildings in the area and of national importance, the Royal Mews has immense historical and architectural value in its relationship with Hampton Court Palace and at the same time with the Green, as it was where the horses were put out to pasture.

Fig. 21 Illustration of the Green, circa 1700. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

The principal material of all the buildings in this row is soft brown and plum brick, with a rare survival of late timber framing in 2 Palace Gate. The Victorian Rotary court, with its white stucco façade, lies between Georgian houses creating a visual contrast.

Campbell Road

Campbell Road lies on the north side of the Green and displays a cul-de-sac street pattern, and cohesive townscape. The road terminates with Hampton Court House which forms a prominent feature, and on the right side of the road there are cottages of two storeys and Georgian brick houses of three storeys. Houses such as Prestbury House are dominant, with their front gardens, black iron railings, ornamental gates, and surviving original features.

Fig. 22 Prestbury House

The cottages have recessed entrances and roughcast walls. The houses all have their rear boundaries directly facing onto Bushy Park and the rear facades of some are incorporated into the Park’s boundary wall. Hampton Court House includes a historic garden containing a pond, shell grotto and rustic gothic hut.

Hampton Court Road East

Hampton Court Road East lies between the boundaries of the Bushy Park Conservation Area and Hampton Court Palace itself. Development has been continuous since the 18th century: it retains a high quality townscape with phases of development strongly connected to the Palace. The Georgian architectural style is predominant on the west side of the road, from The Craven House to the Bastians, which was developed in a ribbon-like pattern between the boundary wall of Bushy Park and the road. Most of these buildings were originally residential, set back from Hampton Court Road behind front gardens. Over time these gardens were built over, particularly towards the eastern end nearer to the Palace, providing ancillary commercial premises and services in connection with the growing tourist industry. Only a few shopfronts now remain as a historical reminder of the past commercial use; most have been converted, altered or removed.

There are some later residential developments (Parkview, No.41, No. 43, and Kingswood) which punctuate the long stretch of open space within the eastern part of Hampton Court Road. From The Walls building to Bushy Lodge, these houses and cottages are sited significantly far from each other, where nature predominates on both sides of the road.

The dominant material is brick, with slate roofs and front gardens. Some houses also face at right angles away from the road with their gardens and entrance to the side to afford more privacy and peace from the busy thoroughfare. Most of the properties in Hampton Court Road East are two or three storeys high, creating a cohesive domestic scale which is enhanced by various designs and sizes of dormer windows and chimney stacks.

The remaining buildings on the other side of the road are strongly connected to the Palace. In fact, Wilderness House stills remain inside the Palace walls. A row of buildings on both sides of the Lion Gate is predominantly two-storey high, brick built with the King’s Arms featuring a rendered façade. Ivy House and the Hotel are the only remains of the relationship with the Palace as buildings providing services to the workers.

There are modern developments located along parts of the street, however these are in keeping with the scale and character of the historic townscape.

A feature of Hampton Court Road East and Campbell Road is that the boundary wall of Bushy Park has, in most cases, been incorporated within the rear elevations of the houses that back on to Bushy Park. Consequently, the fronts and backs of the buildings are of different periods and styles.

Fig. 23 View from The Kings Arms to the Bastians

Fig. 24 Clarence Cottage

Fig. 25 Lion Gate Mews

Hampton Court Bridge

Hampton Court Bridge, half of which lies within the Conservation Area due to the borough boundary, is listed Grade II, and is situated to the south of the palace. It is in this location that the main group of buildings were sited to provide accommodation and services for the court from the late 17th century. Furthermore, it has maintained a strong connection between the village and the train station since the coming of the railway in the mid-19th century.

Spatial Analysis

The Green is a large open space of 7.13 hectares with uninterrupted views across the area. It has a characteristic cross path with an avenue of mature trees on the external boundaries, creating a wide grassy green space in the centre. It provides a large public space, with a strong visual connection with the historic landscapes of Hampton Court House and Bushy Park both of which are included on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens maintained by Historic England.

The green space has remained largely unchanged since the 18th century largely due to the removal of rights to develop on the space by the Crown. This has also allowed the street pattern of Hampton Court Road to remain largely unaltered.

Hampton Court Road forms a bisected grid pattern moving to the west and east of Hampton Court Palace, and enclosing Hampton Court Green on two sides. Hampton Court Road west is wide, with the buildings set on the south side of the road and Bushy Park on the north side. Plots forming the eastern part of this road are generally narrow and long with little space between buildings. There is a consistent building line which introduces an enclosed feel. The architectural style of the buildings is consistent as well as the height with most buildings being three-storeys. The exception is the Royal Mews which is two storeys. To the west, the buildings are largely detached with the gaps allowing glimpses to the river beyond and form a later development of the area. Height and scale is also consistent, being two storeys.

Fig. 26 Hampton Court Road west

Campbell Road is a narrow street with a gravel surface; the residential buildings are situated on the north side of the road and Hampton Court Green on the south side. The exception is Hampton Court House, which is sited at the end of the cul-de-sac, with a small parking area adjacent to the entrance.

Fig. 27 Campbell Road

Hampton Court Road East is wide and long, with buildings on both sides until the Lion Gate. The palace gates and walls are an important focal point in the street scene providing an enclosed feel to the south. The predominant height is two storeys, with different stages of development along the road. The principal style is Georgian, but later architectural styles coexist and add to the varied historic character of this part of the Area.

Gaps between houses is an important feature beyond the Bushy Park entrance, with detached houses predominating, many recessed behind high boundaries, and sometimes with limited visiblity from the street scene.

Fig. 28 Hampton Court Road east

The area overall is not densely developed; natural landscape is predominant which makes a significant contribution to the spatial character of the area. The provision of front gardens, trees along the road, and presence of the royal parks create a rural character strongly linked to Hampton Court Palace.

Open Spaces, Parks, Gardens and Trees

An overview of private and public spaces; front gardens, trees, hedges, street planting, historic parks and gardens, civic spaces and their contribution to the character and experience of an area.

Hampton Court Green is the primary area of public open space, adjacent to Hampton Court House. Although Bushy Park is not within the Conservation Area it provides the green backdrop and the rural landscape setting to the north side of Hampton Court Road East.

Fig. 29 Northwest of the Green

Fig. 30 Path of the Green

The street trees are quite abundant around the palace but there are few within the residential area. The substantial number of trees around Hampton Court Green, and the front gardens of houses with their shrubs and trees, lend additional green character to the area.

Hampton Court House has a historic landscape designed by Thomas Wright, which includes a shell grotto and an artificial lake. It is included in the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens at Grade II* and forms an important historic landscape with many listed garden structures.

Fig. 31 Trees outside Hampton Court Palace

Fig. 32 Hampton Court House

Views

The Borough of Richmond has protected views through the planning process, adopted in the Borough’s Local Plan (also note the emerging Local Views Supplementary Planning Document).

The unique form of the Conservation Area with its large open spaces allows views looking towards remarkable landmarks such as Hampton Court Palace, Hampton Court Green, and Hampton Court Bridge.

- Views looking towards Hampton Court Palace: The views of the palace are limited due to the high boundary walls. On Hampton Court Road east, the iron gates provide some visibility into the palace grounds at certain points.

- Views looking towards Hampton Court Green: The Green is visible from many points in the area due to its central position. The historical relevance of the Green is its protection as open space granted by the Crown. Low wooden fence rails surround the Green, leaving the greenery and trees as a relevant visual feature within the conservation area.

- Views looking towards Hampton Court Bridge: The bridge, built in a neo-classical style to complement Sir Christopher Wren's additions to Hampton Court Palace, is an important landmark and river crossing in the area. It retains a strong relationship with the River Thames and is still preserved in the back gardens in Hampton Road west but not from the street view.

Architecture/Built form

A description of the dominant architectural styles in the area, the types and periods of buildings, their status and essential characteristics, and their relationship to the topography, street pattern and skyline. Also important is their authenticity, distinctiveness and materiality.

Most of the buildings in the Conservation Area are designated as either statutorily Listed Buildings or Locally Listed Buildings (Buildings of Townscape Merit). There are 28 listed buildings, 38 Buildings of Townscape Merit, one Grade II listed bridge and two registered historic parks and gardens.

Many of the houses in the area were built or altered in the Georgian period, with older buildings located closer to the Palace, including the Royal Mews. There is a clear difference in terms of the typology of houses according to their location. In Hampton Court Road West, houses are detached but more closely positioned, with front gardens facing the road and back gardens running down to the River Thames. In Hampton Court Road East, houses generally date from the Georgian era or later with few modern buildings inserted between them.

The major features of the Conservation Area are:

- Front gardens with brick walls and hedges.

- Cast iron work: gate posts, railings and lamps.

- Timber sash windows.

- Soft red Georgian bricks.

- Tall brick chimney stacks.

- Pitched slate and tiled roofs.

- Traditional style dormer windows.

Palace Gate

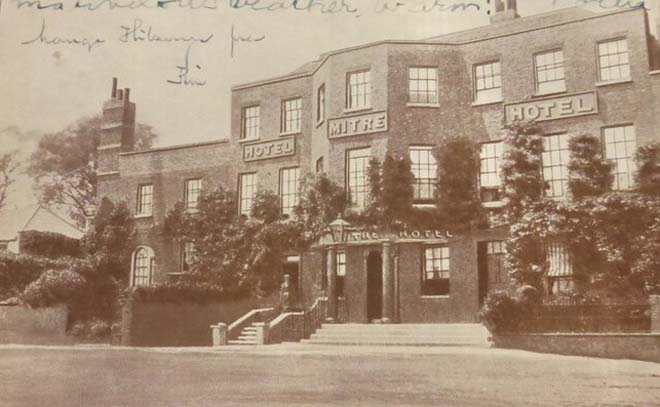

The south side of Hampton Court Road includes several 18th-century Georgian buildings. Set back from the main road, now separated by a car parking area, it has a feel of an individual island of rows facing the main gates of the Palace. The Hampton Court Road frontage starts on the north side of Hampton Court Bridge with the base of the bridge pavilion. This is visually connected with the Mitre Hotel extension, a glazed structure that faces the Thames with a classical-style entrance portico.

The mid-18th century Mitre Hotel is a key element of this frontage and important historically at the intersection of the bridge and the road. It is three storeys in height with a large central bay and constructed in soft brown brick with dressed red brick window arches, small-pane timber sash windows, flat parapet and pitched tiled roof behind with projecting chimney stacks. A large wisteria dominates part of the main façade. The building provides the first view once you cross Hampton Court Bridge and forms an important backdrop to the river.

Fig. 33 Views of Mitre Hotel from Hampton Court Bridge

Fig. 34 Mitre Hotel on the left, The Mute Swan in the centre, Palace Gate on the right.

Adjoining the Mitre building to the north is the Mute Swan whose brick façade is painted white and has an outdoor seating area at the front. Adjoining is 2 Palace Gate, of 18th century origin with later additions, and of three storeys in stock brick with rendered rusticated ground floor and carriage entrance.

Adjacent is 1 Palace Gate, a late 18th century building of two storeys with a traditional shopfront to the ground floor. In the corner, Palace Gate House, an early 18th century building of two storeys, has historically had a number of uses and was split in two at the beginning of the 20th century. It has a stepped raised entrance on the ground floor of the principal front and a two-storey wing on the north front. In front of the Palace Gate is a George V pillar box, which replaced the first pillar box in the village. Overall, there is a consistency of form and architectural detailing to this building group with sash windows which reduce in size to each floor.

Opposite there is a grade II listed K6 telephone box in front of the Trophy Gates, designed in 1935 by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in a neo-classical style.

Fig. 35 Row of buildings: Mitre Hotel, The Mute Swan and 1 and 2 Palace Gate

Fig. 36 View from Palace Gate towards the River Thames.

Fig. 37 Showing the roadside where the Hampton Court Palace is located.

Fig. 38 Postcard of Mitre Hotel in 1933. Sadler Bros, Proprietors

Hampton Court Road West

Contiguous to 1 Palace Gate is The Green; an important 18th century building with a consistency of form and representative of this important early phase in the development of the area. This side of Hampton Court Road is connected to Palace Gate House on the approach to the bridge, creating a uniform frontage that persists until the break in the built streetscape before Rotary Court.

Fig. 39 Hampton Court Road west

At the end of this group of historic houses, is an alley that follows the boundary line to the back, which leads yard that was used by the carpenter for the Palace. It still preserves the old-period atmosphere, contrasting with the main road with retained historic features such as the cobbled pavement and many of the oldest buildings in the area. Its location, not visible from the main road, has helped preserving most of its original features.

The Old Office House is a key element in the yard, where Sir Christopher Wren had his drawing office, and not visible until one arrives at the end of the alley. It acts as a centrepiece of the alley with an exposed timber frame and a timber-clad cottage.

Rotary Court is a Victorian Italianate three-storey composition with three-storey wings at each end. It has a rendered façade with rustication on the ground floor. It creates a juxtaposition with the buildings alongside, creating a clear separation between rows and providing a principal example of Victorian architecture in this part of the Conservation Area.

Fig. 40 View of the Royal Mews from the other side of the street.

Adjacent is the grade I listed Royal Mews arranged around a quadrangle with access through an archway, brought from Hampton Court Palace in 1537. Elevations are constructed in red brick and the two-storey building features a tall pitched tiled roof, attic floor with dormers and tall prominent brick chimney stacks. The central gateway with its stone arch offers a clear view of the internal courtyard with its cobbled surface and metal features such as the torch holders and iron wall guards at the corners.

Further west along Hampton Court Road is a group of buildings that are mostly Buildings of Townscape Merit. All are two storeys with attic storeys, varied fenestration and rendered facades.

Fig. 41 View of Hampton Lodge

Further west the character of the road begins to change, with large, detached 19th and 20th century houses, mostly set back from the road in substantial gardens and fronted with brick boundary walls. The western-most boundary of the conservation area is marked by a petrol station and a new development (Riverholme) which is four storeys in height and set back from the road.

Fig. 42 Old House

Fig. 43 Faraday House

Fig. 44 20-31 The Green, Hampton Court Road west, 1971. Richmond Local Studies Library.

Fig. 45 Rotary House showing as the Whitehall Hotel in the 1920s. Richmond Local Studies Library.

Fig. 46 Royal Mews c1970. Richmond Local Studies Library.

Hampton Court Road East

The west side, facing the corner of the Palace boundaries, comprises buildings dating from a variety of periods. Directly facing the Green, a row of Georgian houses dominates the streetscene. They are generally two and three storeys in height with basements and built of soft brown brick with red brick dressings and a variety of rooflines; painted white brick has become a common feature in the frontage.

Towards the Lion Gate, from the Kings Arms Hotel, the type of houses is more varied, with cottages and new developments creating a mix of scale and form with some vernacular elements. Georgian houses are located mainly on the west side, closer to Lion Gate Hotel. Further from the palace, detached cottages are predominant, with a few new developments.

The current frontages are later extensions, built to provide space for the tea rooms and other uses historically supporting visitors to the Palace and consequently mostly converted to residential use.

In most cases these further changes relate to the ground floor front extensions of the principal buildings. Myrtle House retains the only surviving shopfront illustrating the period of commercial activity along this stretch of road. Laurel Cottage and Bushy Lodge, situated on opposite sides of Hampton Court Road east at the eastern-most point of the Conservation Area, form the transition point where trees and green space dominate the landscape and skyline on both sides of the road between Bushy Park and Hampton Court Park. Set back behind the avenue of trees are the tall brick boundary walls of both royal parks which enclose the park landscape beyond.

Fig. 47 View of No.1 Hampton Court Road east to Court View House. Myrtle house is located in the middle of the row.

From the western-most point of Hampton Court Road East (near its junction with Campbell Road) and towards the Lion Gate Hotel by the main entrance of Bushy Park, the type of houses is more varied, with cottages and new developments creating a mix of scale and form with some vernacular elements. Georgian houses are located mainly at the western-most end of this stretch. Beyond the Lion Gate Hotel eastwards towards Hampton Wick are several detached houses, in addition to terraced and semi-detached properties.

The boundary wall is incorporated within the rear elevations of most buildings backing onto the park. These rear elevations are visible from Bushy Park and present an interesting mix and quality of architectural details. The type and pattern of fenestration sometimes differs from the front elevations including the use of sash windows, bay windows, casements, and balconies which are also present. The dominant material is soft brown and mixed stock brick, but other finishes such as timber boarding and render feature.

Fig. 48 Back elevations from the Bushy Park

Fig. 49 Hampton Court Road east

Fig. 50 Lion Gate

Fig. 51 Kings Arms Hotel back elevation, view from the Palace.

Fig. 52 View of the street from Bushy Park entrance pedestrian cross walk.

Fig. 53 Anne Boleyn Cottage,1974. Richmond Local Studies Library.

Fig. 54 Lion Gate in 1895. Montifraulo Collection.

Fig. 55 Kings Arms Hotel. The collection of John Sheaf

Campbell Road

Campbell Road forms a cul-de-sac, with buildings on the north side and the Green on the south side. It is a narrow access road, with buildings of mixed height and scale, and has a strong rural character. It forms a connection between the Green and other parts of the area.

The row of buildings on the north side are formed of a mix of Georgian and Victorian houses and cottages with a variety of well-preserved features, such as ornamental metal gates and plaster decorations. At the end of the road, Hampton Court House contributes to the exceptional architectural value of the street.

Hampton Court House functions as a landmark at the termination the road. It is a large Georgian house of brown brick with a dome which punctuates the skyline. The back elevation, visible from Bushy Park, has wide sash windows with a classical doorcase at the back elevation door that illustrate its initial design to face the Bushy Park rather than the Green.

The cottages and houses along Campbell Road all have their back elevations visible from Bushy Park, preserving in some cases, period chimneys without alterations, and access to the park. Also, it is very distinguishable that the houses are using the boundary walls as part of their structure, having features of the wall still visible. The difference with the main and rear elevations is striking, becoming a clear example of how the area developed during the 19th century.

Craven House is a good example of a Georgian house, being located at the beginning of Campbell Road and facing the Palace. It was where a refreshment house for the palace workers was located during the 18th century. It has a central pedimented entrance door with Doric columns surmounted by a cast-iron balcony that presides over the street scene.

Fig. 56 Campbell rd. from The Green

Fig. 57 Back elevations from Bushy Park

Fig. 58 View of Campbell Road from the entrance towards Hampton Court House.

Fig. 59 Bushy Cottage

Fig. 60 The White House

Architectural details

This area includes a variety of excellent examples of architectural details that reinforce its character.

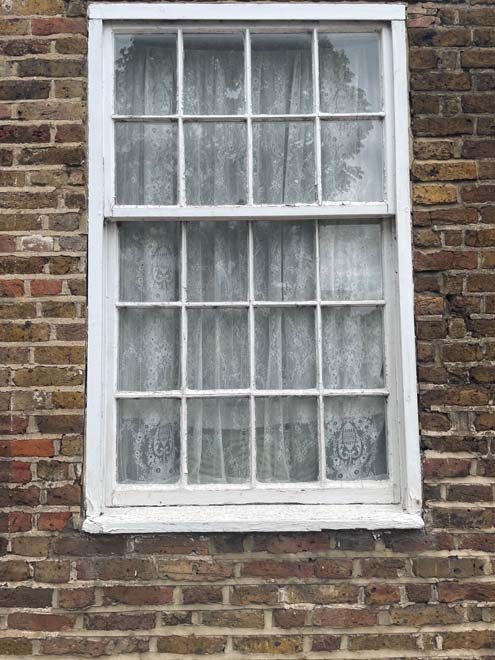

Windows:

Almost all the windows that are found in the area are painted timber sash windows, with a few exceptions including those on older buildings which have casement windows, such as the Royal Mews which also has moulded mullions. This consistency of window form and materiality forms a significant feature of the conservation area, providing unity of appearance to the building and a strong historic character to the area. Whilst there is a consistency in window types, there are subtle differences with the number and size of the panes and thickness of glazing patterns which reflects the age of the buildings.

Fig. 61 Example of a sash window

Fig. 62 Example of a Mullion window, Royal Mews

Fig. 63 Detail at Rustat Lodge (Former Vine House) at Hampton Court Road west.

Roofs:

The area includes a variety of traditional roof lines, some high and partially hidden from the street behind raised parapets. The coverings that can be seen are slate, clay tile, and lead. Dormer windows are a feature of some roofs in the area, mainly in Hampton Court Road west. This variety adds to the richness of the area and represents its gradual development as well as the changing architectural styles of the periods.

Fig. 64 Example of chimneys stacks

Paving:

Paving is fairly uniform across the Conservation Area, with concrete pavement slabs. At the entrance of the Royal Mews, cobblestones are located, being an important surviving and increasingly rare historic floor surface that illustrates the historical use of this space. In addition, behind Faraday House and Old Court House, further cobblestones have been retained, also illustrating the historic use of this space as the working yard for the palace carpenter. Campbell Road presents a granite curb finish.

Fig. 65 Detail of the concrete pavement slabs pavement

Fig. 66 Detail of cobbles

Fig. 67 Detail of pavement in Campbell rd.

Chimneys:

The area still retains many historic chimney stacks that make a significant contribution to the skyline. This is particularly the case on Hampton Court Road West where the ornate Tudor stacks of the Royal Mews form a highly distinctive feature and provide a visual link to the prominent chimney stacks of Hampton Royal Palace.

Fig. 68 Royal Mews chimney stacks

Fig. 69 Detail of a chimney stacks and pots

Fig. 70 Tudor-style chimneys on the White House, Campbell Road.

Render:

There are a few examples of buildings which have a rendered finish in the area, including Rotary House with its stucco front and the cottages on the east side of Hampton Court Road with their roughcast render. This adds visual interest to the streetscene and provides a welcomed break to the consistent use of brick.

Fig. 71 Example of roughcast render, Henry VIII Cottage

Timber weatherboard:

The only timber weather-boarded house in the area lies behind Hampton Court Road. Even though it is located in an historic yard, it adds historic character in its relationship with the surrounding buildings and reflects its period of construction and original use.

Fig. 72 Detail of a weather-boarded façade, Kings Store Cottage.

Shopfronts:

The shopfronts in the area are limited as it is now predominantly residential. Only five survive.

- Old Park House, Hampton Court Road: Mid-20th century shopfront, recessed doorway, white stall risers and a large area of glazing.

Fig. 73 Detail of the Old Park House shopfront at Hampton Court Road.

2. 1 Lion Gate, Hampton Court Road: Repainted shopfront, without brackets and mouldings and of simple design. Late 20th century.

Fig. 74 Detail of the shopfront at 1 Lion Gate, Hampton Court Road

3. 2 Lion Gate, Hampton Court Road, Kings Arms Hotel: Presents typical features of a traditional shopfront although now part of the hotel and pub, glazing divided into small panels on the left side. Later alterations on the right side.

Fig. 75 Detail of 2 Lion Gate shopfront

4. Myrtle House, Hampton Court Road: Altered traditional shopfront, glazing divided into small panes, bow windows supported by struts and fanlight over the door.

Fig. 76 Myrtle House, Hampton Court Road

5. Palace Gate, Hampton Court Road: Late 19th century- early 20th century, carved console brackets enclosing the fascia. Glazing is divided by white timber mullions, arched, and decorated with ornaments resulting in an interested fenestration which contrasts with the simple sash windows above.

Fig. 77 Detail of the No. 2 Palace Gate shopfront

Porches:

The porches in the area consist predominantly of two styles, neo-classical front door cases for Georgian houses and gabled pitched roof porches for cottages.

Fig. 78 Example of a porch, Riverside cottage

Front boundary treatments

One of the main features of the area is its front gardens, with brick boundary walls and iron railings and gates. It is characteristic to display the names of houses on the front gate or door, as the name plates on them provide a special rural feeling throughout the area. Bushes, hedges, trees and ivy along front boundaries add a green setting and enhance the character of the area.

Fig. 80 Examples of boundary treatments

Doors and surrounds:

The external doorcases found in the area are mainly in a classical style with few examples of fanlights. They contribute significantly to the architectural character of the streetscape.

Fig. 81 Detail of a Palladian-style classical doorcase

Fig. 82 The Ivy Lodge Entrance, a Palladian-style classical doorcase

Gates:

Georgian ornamental gates are a feature of the Conservation Area, with a variety of styles, ornaments, and colours. Wooden doors set in high brick boundary walls feature a collection of colours and styles, but block views of the houses from the plot behind.

Fig. 83 White House gate

Fig. 84 Detail of the Old Court House gate

Manholes:

Around the area there is a range of utility access holes; closer to the Royal Mews are a few interesting examples of timber and cobble manholes.

Fig. 85 Example of Manholes

Hampton Court Palace Gates:

The Gates of the Palace are an important feature of the Conservation Area. Included within the boundaries are the Flowerpot Gate, Trophy Gate and Lion Gate, all of which lie on Hampton Court Road.

Fig. 86 Main gate (known as Trophy Gate) of Hampton Court Palace

Fig. 87 Lion Gate

Blue Plaques – English Heritage

Sir Christopher Wren blue plaque on Old Court House.

Fig. 88 Blue Plaque of Sir Christopher Wren

The Toy Inn

Fig. 89 Toy Inn plaque at the Main Gate of Hampton Court Palace.

Pavilions:

Four pavilion bases, two at each end of Hampton Court Bridge. The pavilions were never completed.

Fig. 90 Detail of the pavilions on Hampton Court Bridge

Benches:

The only group of benches in the area are located in front of the Kings Arms Hotel.

Fig. 91 Detail of the benches in front of the Kings Arms Hotel

Street furniture:

- The pillar box standing today in front of Palace Gate is on the site of the original pillar box for the village and form an important historic street feature.

- K6 Telephone Kiosk outside Hampton Court Palace near the main entrance.

- Low wooden posts and fence rails surround the perimeter of Hampton Court Green, separating the Green from the road and residential area.

Pillar box

Wooden fence

Fig. 92 Showing: Pillar box, Wooden fence, and Telephone kiosk

3. Management Strategy

Summary

This Management Plan outlines how the Council intends to preserve and enhance the character and appearance of the Conservation Area for the future. The Council has a duty to formulate and publish these proposals under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990.

This Appraisal has assessed the quality and condition of the Hampton Court Green Conservation Area. Several site visits were undertaken in September and October 2022, where the area was observed and photographed.

The Appraisal has summarised the strengths and weaknesses of the Conservation Area, and this management plan sets out a strategy to consolidate and enhance these strengths and prevent further erosion of the area’s special architectural and historic character.

Hampton Court Green Conservation Area remains essentially unaltered, with a few modern developments on the eastern side. The buildings facing the Green have preserved historical features and a strong architectural character, being generally all statutorily listed. Alterations from the 19th- 20th centuries to allocated shopfronts are predominant in Hampton Court Road East, now reconverted for residential use. The area is well preserved, but there are some unsympathetic external finishes, satellite dishes and replacement of original windows which have a negative effect on the character and appearance of buildings.

The overall conclusion of the Appraisal is that all areas of the Conservation Area are worthy of inclusion. It is hoped that this clearer, more extensively illustrated Appraisal will assist the Development Management Process in making more informed planning decisions in respect of the area’s character.

Under section 71 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, local planning authorities have a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of conservation areas in their area, from time to time. Regularly reviewed appraisals, or shorter condition surveys, identifying threats and opportunities can be developed into a management plan that is specific to the area’s needs.

Problems and pressures

The majority of the buildings in this area are listed or are included in the local list of buildings of townscape merit. The quality of architectural details and their historic association forms part of their special interest and that of the conservation area.

- The traffic volume has been a problem since the opening of the palace in the 19th century to the public.

- A car park was built on the northwest side of the Green to provide services to the visitors. The loss of that small part of greenery, the non-aesthetic look of a car park, negatively impact the character of the area.

- The Flowerpot Gate, statutorily Grade I listed, is in poor condition.

- Placement of satellite dishes in prominent locations.

- Lack of maintenance of boundary walls, gates, windows, and doors.

- Buildings that are unoccupied and/or in poor condition.

- Altered shopfronts with inappropriate features.

- No regulated parking at Campbell Road affects the perception of the detailed facades.

- Inappropriate fascia signs.

- Pavement signs in the middle of the street and inappropriate fascia signs.

- Loss of traditional architectural features and materials due to unsympathetic alterations.

Opportunities for enhancement

- Preservation and enhancement of the historic character of the area and its historic relationship with the palace.

- Extend sealed gravel surfacing around the Hampton Court Palace and Hampton Court Green area.

- Coach/ car park on the Green: explore possible improvements with Historic Royal Palaces, including a more appropriate surfacing.

- Bus shelter: Transport for London could seek an improved design for the key location on the Green opposite the Palace in particular.

- Encourage the retention of original features and enhancement of using traditional methods to preserve them.

- Pedestrian guard rail by roundabout: replace with bollard and rail if required.

- Discuss with Royal Parks about the use of the Green and improving facilities.

- Protection of key views and vistas, particularly those identified in the emerging Local Views Supplementary Planning Document (SPD).

- Retain cobblestone pavements.

- Signposting / interpretation for visitors. Royal Palaces have proposed this on the Green and is intended to be implemented.

- Retain and enhance front boundary treatments.

- Enhance the quality of Campbell Road by regulating the car parking to be cohesive with the rest of the area.

Design Guidance

The design guidance below sets out how good quality design helps to both preserve and enhance this Conservation Area. The guidance will set out advice relating to alterations which require planning permission.

Windows

Windows make a significant contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace, so it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns and styles. In Georgian and early- to mid-Victorian terraces, each half of the sash is usually wider than it is high and divided into six or more panes. Later Victorian, and Edwardian buildings often employ a simpler pattern, with the sashes either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar. More elaborate Victorian villas often have multi-pane top sashes and single-pane bottom sashes

This area presents predominantly timber sash windows, with a few examples of earlier periods, where windows were simpler in form and scale. Bay windows in back facades and Georgian houses are also found in the area.

It is encouraged that in the first instance, original timber sash windows are retained and replaced. If replacement is required, all aspects of the window should be considered, including opening type, glazing bar patterns, horns to sashes, and depth. Windows should be timber sash and replicate the original glazing pattern. Timber frames are not only the most appropriate option but are more sustainable being a natural material which helps reduce the use of single-use plastics, often found in other windows. Timber windows also have the benefit of being more cost effective, being much more durable and repairable than alternatives, and there are options to maintain their appearance while introducing energy saving and noise reducing features.

Single glazing is perhaps the most common window type. As such, simple like-for-like replacements would likely cause the least harmful impact on the existing appearance of a building and therefore the character and appearance of the area. Like-for-like replacements also benefit from being able to be carried out without the need for planning permission. Existing windows can often be improved through secondary glazing, where an additional glass layer is installed behind an existing window. Secondary glazing is an unobtrusive option to increase efficiency, reduce noise, and avoid intervention to existing fabric, often performing as well and lasting longer than double glazing. This approach also often benefits from not needing planning permission.

Where appropriate and where there is justification for full replacement, slimline double and triple glazing with timber frames helps maintain a consistent appearance, while offering similar benefits to secondary glazing. Where double/triple glazing is accepted, black spacing bars and seals should be avoided – these should instead be white to blend with the frame. Trickle vents should be avoided or well concealed within the frame to maintain consistency with historic appearance.

Windows to contemporary development can vary in detail but it is still important to consider their design in relation to the character of the area.

Front boundary treatments

One of the main features of the area is the front garden brick boundary walls and iron railings. The most significant and celebrated boundary walls with its impressive entrances is that surrounding Hampton Court Palace and form the boundary with the Hampton Court Palace Conservation Area. Most boundary walls are protected as far as they are listed or are above one-metre-high fronting a street or public highway whereby consent is required for any alterations or demolition. Bushes, hedges, and trees along the boundary provide more greenery and add the semi-rural, verdant character of the area.

Where they contribute to the character and appearance of the area, boundary treatments are encouraged to be preserved and their original fabric and ornamental features such as gate piers and finials and iron railings repaired. Where any original boundary features have been lost, every encouragement is given to their reinstatement to enhance the character and appearance of the conservation area.

Roof alterations and extensions

Original clay roof tiles to all roofs (including porches) should be retained, reinstated and repaired on a like for like basis in terms of design, material, size, camber and colour.

Ensuring that tiles are carefully replaced to match the size, shape, camber and colour of the existing tiles enables the roofs of individual houses to interlock smoothly into the roofs of their neighbours, ensuring a consistent finish to the groups. The use of tiles of any other size, shape, colour or texture would compromise this harmony. The use of unsympathetic modern interventions such as concrete roof tiles or imitation slates should be particularly avoided.

Original chimneystacks and pots should be retained or reinstated.

New dormers or rooflights should not be installed on front roof slopes or side roof slopes visible from the public realm where they would compromise the uniformity of a group or terrace.

The area presents a cohesive roof typology, notably gable roofs with clay tiles. Rear elevations with dormer extensions are typical features in Georgian buildings.

Painting and External Finishes

External finishes are common features in the Conservation Area and have been carried out to varying levels of quality and effect. It is less successful where there are one or two properties which differ from the rest of the terrace as this disrupts the architectural cohesion of the terrace.

Painting and external finishes are recommended only when it forms part of the original design of the building. this should be regularly maintained and refreshed to prevent deterioration and water damage and to maintain the character of the building. Where non-original painting has been applied, this risks damaging the original brick beneath.

Shopfront and signage

The quality of design of shopfronts varies within the Conservation Area. As stated within the Appraisal, only five buildings retain shopfronts with varying ages and styles. Traditional (and traditionally designed) shopfronts make an important contribution to the character and appearance of the historic environment. Any existing historic shopfronts, or components of historic shopfronts, should be maintained and repaired in the first instance. Where traditional forms have been replicated, or contemporary shopfronts inserted, these should continue to follow traditional designs if they need to be altered or replaced. Any new or replacement shopfronts will need to maintain or improve the appearance of the existing shopfront. Guidance on the design of new shopfronts can be found in the ‘Shopfronts’ Supplementary Planning Document’.

Signage should replicate traditional styles with painted or applied letters to the fascia and simple hanging signs. Modern signage, including corporate branding, internally illuminated projecting box signs, and box fascias are discouraged. Projecting/hanging bars should be sympathetically placed and attached to the fascia or building face. Where hanging signs are proposed, these should use a traditional bracket and be of a simple design.

Shopfront Security

Projecting shutter boxes have a negative impact on the appearance of shopfronts and are not acceptable in conservation areas, nor are solid or perforated shutters. Unless they are continuously back-lit, the perforation is only really apparent directly in front of the shopfront itself – from other angles and from further away they seem solid, and solid shutters create an unwelcoming, unattractive environment. By blocking the interior, they also prohibit passive surveillance and are more likely to be graffitied, which would cause further harm to the character and appearance of the conservation area.

Instead, there are other solutions which would be more suitable, and these are outlined in the Design Guidelines for Shopfront Security Supplementary Planning Guidance. For contemporary shopfronts, more passive security measures can be effective, such as laminated glass, which is not readily apparent and therefore mitigates detracting from the appearance of the shopfront. Lattice brick-bond grilles can be installed internally behind the windows, with the box inserted into the ceiling – this prevents an external projecting box and the internal box from being visible through the shop window. This would allow for an appropriate level of security, while minimising the visual impact of shutters on the external appearance of the shopfront, and therefore of the conservation area. It also allows for passive observation by keeping the inside of the shop visible.

Energy Efficiency

Introducing energy efficient measures can reduce carbon emissions, fuel bills, and improve comfort levels. It is important that the appropriate course taken should be informed by the context of the building being improved, with each building having different opportunities and restrictions.

Not all solutions will be appropriate across the Conservation Area, and the ‘Whole Building Approach’ advocated by Historic England encourages a case-by-case approach, which fundamentally considers the context, construction, and condition of a building to determine which solutions would be the most suitable and effective. A wide range of guidance and advice on many aspects of improving energy efficiency in history buildings can be found on the Historic England website

Solar Panels

Solar Panels and equivalent technology are most suitably placed on rear or side elevations where they are hidden from the public realm –principal elevations and roof slopes facing the public realm are less appropriate as they generally make the most substantial contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. New technologies, such as PV panels disguised as slates and sitting flush with roof materials, may be suitable in the appropriate context, and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Street Scene and Public Realm

The public realm is an important part of the historic environment as it makes a significant contribution to the setting of buildings. Public spaces which are cluttered with unrelated elements can detract from the appearance of the area. It is therefore important that high quality materials and workmanship are used to develop good streetscapes and public spaces, which can contribute positively to the historic environment.

The pavements within the Conservation Area are relatively free of clutter, which is a positive aspect considering that many are narrow, with buildings sitting hard up against the pavement. Where present, street furniture is spaced evenly and does not dominate the pavements.

Good streetscape and public realm can be achieved through the use of high-quality additions which reflect the character of the area and contribute to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. The positioning of street furniture should be rationalised to ensure they are in the best possible locations and of appropriate design. Lamp and signpost columns should be green or black in colour and appropriate for the scale and character of the Conservation Area. Surviving cast-iron street name plates should be identified and retained, and historic street furniture should be refurbished and retained. The use of traditional paving slabs and granite kerbs should be promoted to improve the quality of the pavement throughout the Conservation Area. Elsewhere a sealed gravel finish to existing bitmac surfaces would improve the appearance of pavements in the historic core. Any opportunities for street tree planting should be explored. Further guidance on the public realm can be found within the Council’s Public Space Design Guide.

4. References

- Heath, G.D. (2000) Hampton Court: The story of a village. Middlesex, England: Hampton Cort Association.

- The Hampton Court Palace – Gardens, Estate and Landscape Conservation Management Plan (Historic Royal Palaces, 2011) Hampton Court Palace Views Management Plan (Historic Royal Palaces, 2005)

- Alphonse, L.E.P. (1885) The history of Hampton Court Palace. London: G. Bell and Sons.

- Archive photographs: Richmond Local Studies Library

- Historic maps: National Library of Scotland

- Historic England

- Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

- British Library

- The Collection of John Shaef

- Historic Royal Palaces

- Sir John Soane’s Museum London