Queen's Road

Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation area No.47

Contents

Part 1: Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principal aims of Conservation Area Appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications.

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication titled Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’.

The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to local conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan and national policies of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

Our overarching duty which is set out in the Act is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

conservation_areas_spd.pdf (richmond.gov.uk)

Buildings of Townscape Merit

Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) are buildings, groups of buildings, or structures of historic or architectural interest, which are locally listed due to their considerable local importance. The policy, as outlined in the Council’s Local Plan, sets out a presumption against the demolition of BTMs unless structural evidence has been submitted by the applicant, and independently verified at the cost of the applicant. Locally specific guidance on design and character is set out in the Council’s Buildings of Townscape Merit Supplementary Planning Document (2015) which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

buildings_of_townscape_merit_spd.pdf (richmond.gov.uk)

Designation and Adoption Dates

Queen's Road Conservation Area was designated on the 14th June 1988.

Following approval from the Environment, Sustainability, Culture and Sports Committee on 17th January 2023, a public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between 17th March and 28th April 2023.

This Appraisal was adopted on 20th November 2023

Map of Conservation Area

Statement of Significance

The Queen’s Road Area was developed during the boom years of the Victorian and Edwardian period when Twickenham was flourishing and has strong surviving examples of residential dwellings from this period. The area has a strong character and visual cohesiveness together with architectural continuity,with Holly Road forming a transitionary zone separating the quieter residential streets.

Historic Development

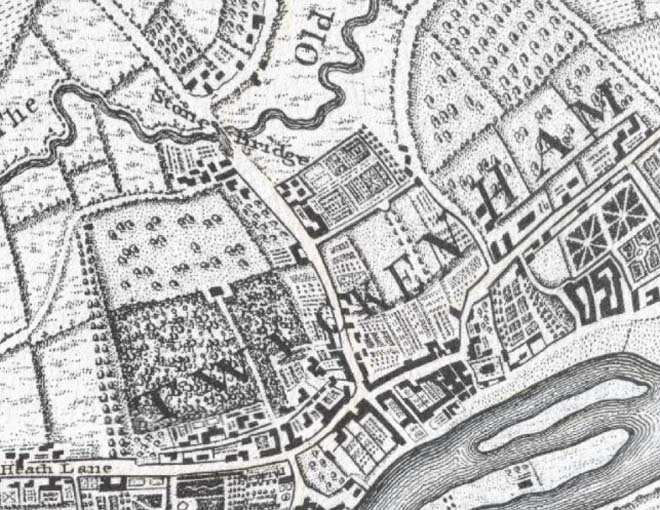

The area which now forms the Conservation Area was once part of one of the open fields of the medieval period. John Roques map 1741-5 (Fig. 1) shows a large house (Holly House, demolished at the end of the 19th century) approached by a formal avenue running north from Holly Road. The nearby Grosvenor House was built in the early 1700s and still survives albeit with an additional upper storey.

The Holly Road Garden of Rest was originally an overspill cemetery for St Mary’s Church and was built in the 18th century. The first place of worship in the area for non-conformists was opened in 1800 on Holly Road for the Methodists and the chapel survives today adapted as commercial premises. A new one was built in 1881 on Queen’s Road, and the first Roman Catholic Church in Twickenham was opened in Grosvenor Road in 1883, with St James RC School following in 1893 – since redeveloped as St James House.

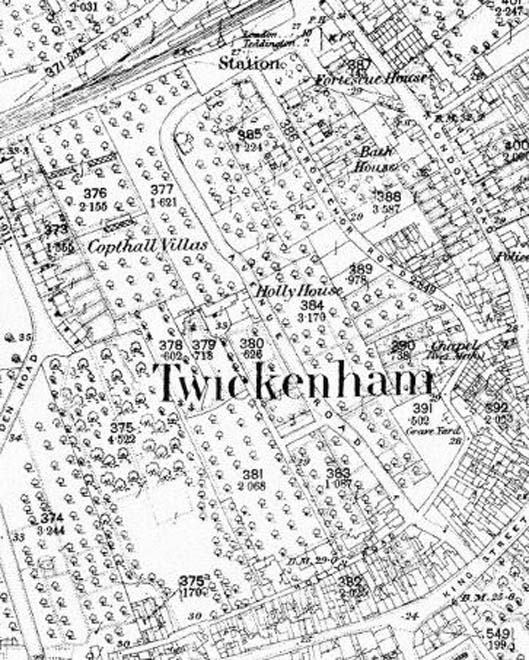

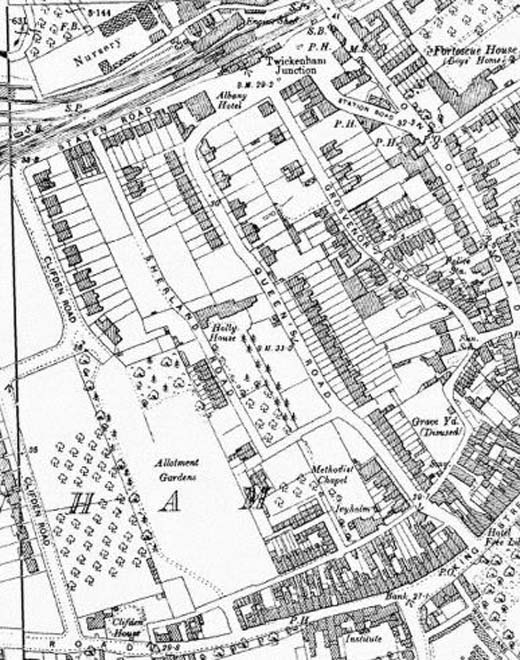

The arrival of the railway in 1848 made a major impact on the area, cutting across the northern edge. The original Twickenham station and its rectangular forecourt were built at the northern end of the newly laid out Grosvenor Road and Avenue Road (later Queen’s Road). Most residential development took place between 1880 and 1895 in the form of imposing terraces or semi-detached villas.

Fig. 1: John Roques map 1741-1745

Fig. 2: OS Map 1866-1893

Fig. 3: OS Map 1895-1898

Fig. 4: The north end of Queen's Road, including the original Twickenham Railway Station, 1928

Fig. 5: Aerial View of the Conservation Area, 1966

Part Two: Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Setting

Queen’s Road Conservation Area is located south of the railway line, to the west of London Road, and to the north of King Street – two of the principal roads of Twickenham. It adjoins Twickenham Riverside (8) Conservation Area to the southeast.

Its development was influenced by the burgeoning growth of Twickenham during the 19th century and its setting, particularly to the south and east, forms the urban town centre. The area to the west is similarly residential in character. To the north, the setting is industrial and urban with the railway line bisecting the residential area from more contemporary flats further north.

Topography

The Conservation Area is relatively flat, with no significant inclines. Holly Road has a gentle curve, more sharply orientating around Holly Road Garden of Rest to the east. Grosvenor Road runs roughly parallel to Queen’s Road, ending at Station Yard, facing the railway.

Buildings and Townscape Overview

Queen’s Road

Fig. 6: Entrance to the Conservation Area from King Street

At its southern entrance, Queen’s Road breaks through to King Street, although only part of Queen's Road is revealed because of its curve (Fig. 6). The view into the Conservation Area terminates with a tall solitary Cedar tree creating a strong silhouette in front of which is the steeply pitched slate roof and stone gable elevation of the former Methodist church. The section of Queen’s Road south of Holly Road is somewhat unremarkable, with the blank elevations of the back land development of the King Street commercial buildings and a single storey commercial unit. As the bend begins, however, there is a striking building found in the old fire station which has an unusual pantiled hipped mansard roof (Fig. 7). Although there are wide pavements, there is a lot of street parking, an overspill of the urban character of Twickenham Riverside’s commercial centre, and a symptom of Holly Road being the main means of access to the nearby car park. Holly Road itself is a transitionary road, beyond which there is a change in character. Here, the noise and activity of King Street is left behind and a quiet residential road emerges, with late Victorian and Edwardian houses with the occasional more recent 20th century intervention (Fig. 8). Generally, there are no formal street trees and greenery is provided by vegetation in the small front gardens. The houses are arranged in terraces or as semi-detached pairs and the predominant building materials are yellow stock or gault bricks and grey slate for roofs. There is a wealth of architectural detail in the form of contrasting red brick decoration, white stucco architraves, string courses, bay windows, and basements.

Fig. 7: The former fire station

Fig. 8: The junction of Queen's Road and Holly Road marks a transition to typical Victorian and Edwardain residential

The height and grandeur of the houses increases northwards along Queen's Road with houses rising

from modest two storey cottages to generous three and a half storey town houses, including lower ground floors. This transition begins opposite the former church (Fig. 9) with a striking late 19th century terrace (Fig. 10). Here, the group have simple but good quality decorative elements including recessed porches and contrasting brick. The long slate roof is punctuated by a short party wall parapet from which wide chimneys topped with lines of pots rise to break the skyline. Also breaking above is the residential Queen’s House, formerly a 1960s office building, refaced in a contemporary cladding as part of its conversion granted in 2015. As part of the development, the 3 storey Lynott House filled in a gap to Queen’s Road, maintaining pedestrian access to the north side to the flats and introducing the taller scale of the buildings to the north.

Fig. 9: Former Twickenham Methodist Church

Fig. 10: Raised terracr with Queens House breaking over the roofline behind

Fig. 11: Lynott House filled in a gap to Queen’s Road and transitons the scale between two groups

At the junction with Sherland Road, a 1980s block of flats sits comfortably with the scale of the surrounding area, being orientated at an angle to the road which mitigates its mass, and by being set into a good-sized garden with mature planting (Fig. 12). The western side continues with a pair of large houses with timber framing to their attic storey which are unlike other typologies in the area (Fig. 13), one addressing the corner, but offering a transition to the regular repeated rhythm of the grey slated gables and bay windows of a long terrace of Edwardian houses which dominate this section of the road (Fig. 14).

Fig. 12: 1980s block of flats sits well within the streetscape in its material, scale, and placement

Fig. 13: Two large detached houses to Sherland Road are unlike other typologies but relate well to the adjacent Edwardian terrace

Fig. 14: A detached house sits adjacent to the otherwise consistent Edwardian terrace, with projecting bays, gables, and porches

Across from Sherland Road, there is a change in the streetscape, not only from an increase in height of the terrace, but through projecting roof gables, slightly wider canted bays of three windows, and deep front gardens (Fig. 15). In contrast to the southern section of Queen’s Road, where the buildings sit close to the road behind well vegetated, small front gardens with well defined, low boundaries, there is change to the houses being set well back. While this has allowed for some large trees to grow which soften the streetscape in oblique views, many front gardens have been converted to car parking and the boundary definition and soft landscaping has been lost, creating visual gaps and disruptions to the leafy suburban character of the area (Fig. 16).

Figs. 15: Taller terrace typology with raised ground floors and projecting gables

Fig. 16: The terraces have deeper front gardens, some of which have an urban appearance due to hardstanding and parking use

At the end of the terrace are three large semi-detached pairs which have hipped roofs (Fig. 17), and Queen's Court, an unusual 1950's building containing flats (Fig. 18). It is of good quality and its unaltered design respects the form of surrounding development and the front garden has survived as originally designed. Across, a pair of detached dwellings contrast in materials and palette to the general area and are set back further than other houses (Fig. 19). Though their scale fits with the general streetscape, their large, paved gardens draw unnecessary attention and highlight their presence rather than offer cohesiveness with the streetscape. Apart from a 1970s block of no particular interest (Fig. 20), the remainder of Queen’s Road has some of the earliest houses in the Area. The tallest houses terminate the northern end of Queen's Road and front gardens return to being small and well defined (Figs. 21-25). The style of the houses varies from Italianate to Victorian Gothic characterised by use of decorative red brick and diamond shaped black ceramic tiles to string courses at eaves level and canted bays. The timber arched Gothic inspired doors are set with recessed arches.

Fig. 17: Semi-detached pairs have hipped roofs over gable

Fig. 18: Queen's Court, an unaltered small block of flats

Fig: 19: This pair are set back further than other dwellings which emphasised their paved front gardens

Fig. 20: A 1970s block of flats has a large footprint on the north-east section of Queen's Road

Fig. 21: Taller pairs with shallower gardens form part of the earliest development in the Area

Fig. 22: A well detailed gothic group

Fig. 23: A simpler group, with sympathetic alterations

Fig. 24: The earliest houses in the Area are located at the curved end of the road

Fig. 25: The northern group are generally more detailed with high quality decorative embellishments such as these window surrounds and brick courses

The curve of the road into Station Yard terminates views to the northern extreme of the Conservation Area, with the early 2000s Swanston Court invitingly leading the eye around the corner (Fig. 26). The former Albany Hotel survives as a public house, an imposing Italianate stucco building (Fig. 27). The former Station Yard is a large, neglected open space in the setting of the Conservation Area which diminishes the building’s appearance. Behind the pub and adjacent to the contemporary flats is an attractive group of Victorian villas along Station Road, of two storeys plus lower ground floor and attic storey in yellow stock brick (Fig. 28). Although the paved gardens emphasise an urban feel which is exacerbated by the overbearing presence of the adjacent concrete wall and railway lines to the north.

Fig. 26: Swanston Court, a modest 00s block of flats mark a transition in character toward the adjacent Albany Hotel and Station Yard

Fig. 27: The Albany address Station Yard, where the original Twickenham Station was located

Fig. 28: This Victorian group faces the railway tracks, giving them a slightly industrial setting

Grosvenor Road

The townscape and general character of Grosvenor Road differ from Queen’s Road, with houses typically terraces of 2 storeys, simple Victorian cottages built in yellow stocks with shallow pitched slate roofs. This creates a slightly more rural feeling, although outside the confines of the immediate streetscape this sense is diluted by the presence of the taller commercial buildings of King Street and London Road, as well as St James House within the Area itself.

At the north end of the Grosvenor Road boundary is a distinctive detached Victorian house, No. 21 (Fig. 29), beside which is a narrow path leading to a single storey weatherboarded and corrugated iron clad building, much altered but having been on site since the late 19th or early 20th century. The long low slate roof is topped with red clay ridge tiles and can be seen between buildings in Queen's Road (Fig. 30).

Fig. 29: A distinct Victorian building which marks the north-east end of the Conservation Area

Fig. 30: The 'Grosvenor Road Room' was associated with a former chapel but has remained vacant for a number of years

To the south of the alley and across the road are two large semi-detached dwellings (Figs. 31 & 32), in yellow and red brick respectively, the scale and style of which are perhaps more fitting with the typologies to Queen’s Road, however, these quickly transition to the smaller domestic cottages which are more typical to the Area. The group to the west side is slightly more detailed and less altered, with inset porches adjacent to large ground floor windows, and pairs of sash windows above (Fig. 33). The cottages to the east, including the group down a short laneway (Nos. 46-58, even) (Figs. 34 & 35), are much simpler single bay cottages, though all in the groups have well maintained front gardens.

Fig. 31: A large detached house more fitting with the character of Queen's Road

Fig: 32: An isolated dwelling, the typology of which is not found elsewhere in the Conservation Area

Fig: 33: A more detailed cottage group with larger windows and recessed porches

Fig. 34: More simple typology to the east side of the road

Fig. 35: This group is set back from the main road but is similar in appearance to the group in Fig. 34, though more altered

The Conservation Area continues along the west side of the road from this point and the cottages are bookended by another taller Victorian House. Here, there is a more substantial back land plot, Messom Mews, which is occupied by a series of 2 storey workshop buildings, pastiche reconstructions of mid-19th century buildings (Figs. 36-38). The presence of the workshops is implied on the street by an imposing three-storey gable end brick building which rises from the pavement on Grosvenor Road and is mid-18th century (Fig. 39). Together they form an interesting group and are indicative of the placement of early industry close to the historic village of Twickenham.

Fig. 36: The entrance to Messom Mews

Fig: 37: Messom Mews maintains the yard and historic pavers

Fig. 38: Messom Mews are a sympathetic reconstruction of light industrial buildings

Fig. 39: The presence of the mews is indicated by a surviving industrial building rising directly from the pavement

Continuing south there are two short well maintained groups of terraced cottages, the depth of their gardens dictated by the slight curve of the road, although the southern group’s gardens have mainly been lost to parking (Fig. 40). Here, the character of the Conservation Area shifts again, with the height, massing, and general appearance of St James House (Fig. 41) and St Mary’s Hall (Fig. 42: 69-71 Grosvenor Road) at odds with the surrounding context. Their overly urban appearance is not helped by the sparse landscaping, with a low red brick boundary wall surrounding a mass of slate chippings.

Fig. 40: The cottages ar the same typology found throughout the Area, though the depths of their gardens vary greatly in response to the curve of the road

Fig. 41: St James House

Fig. 42: St Mary’s Hall, 69-71 Grosvenor Road

The southern terminus of the road at its junction with Holly Road is defined by the presence of Grosvenor House (Grade II), an 18th century 3-storey house set behind iron railings and well landscaped garden (Fig. 43). One of the earliest houses in the area, its setting has been much altered, enveloped by taller building development to the west and north.

Fig. 43: Grosvenor House

Holly Road

Holly Road, medieval in origin, is represented by a narrow lane which begins at London Road and winds around the backs of buildings on King Street. At the junction of Grosvenor, London, and Holly Roads, is a converted works building (Fig. 44), which, along with the short group of cottages (Fig. 45), is reflective of the former working character of the area. The road curves around the Holly Road Garden of Rest, and there is a contemporary terrace facing into it. At the corner of the road is the aforementioned Queen’s House, which dominates the setting of the small park (Fig. 46). The green is surrounded by an iron rail and acts as a buffer between the noisy commercial King Street and the peaceful residential area behind. The main entrance has a sense of gothic drama with a pair of stone capped, full height gate piers framing a large cedar tree which towers behind (Figs. 47&48). As a former overspill burial ground, the space is dotted with grave markers which add interest to the space, with the north and west sections occupied by brightly coloured play areas (Fig. 49).

Fig. 44: Former works building

Fig. 45: Group of worker's cottages

Fig. 46: Queen's House

Fig. 47: Iron rail boundary to the Garden

Fig. 48: The robust main entrance gate

Fig. 49: View north through the Garden, Queen's House at centre

To the west beyond the junction with Queen's Road there is modern office building adjacent to the entrance to the Holly Road Car Park (Fig. 50). Although of no great interest itself, the car park serves as a through route to the residential streets beyond and is well planted at its boundaries, with trees and bushes within that soften its appearance and mitigate its impact on the surrounding environment (Figs. 51-53). It also serves a secondary purpose, housing a weekly farmers’ market, but its connection to and access from King Street is limited. To the west of the entrance is another group of Victorian cottages (Nos. 98-106, even) which, despite their many alterations, contribute to the rural charm of the area (Fig. 54). Further west is a taller plain terrace (Nos. 108- 118, even), the scale of which is more reflective of Queen’s Road, but the simple design fitting with the domestic cottages (Fig. 55).

Fig. 50: A small office building adjacent to the car park entrance

Fig. 51: The entrance to the car park

Fig. 52: A paved pedestrian foot path and mature trees breaks up the openness of a typical car park and allow access through

Fig. 53: Landscaping of the car park avoids an open 'dead space' from imposing on the character of the Conservation Area

Fig. 54: This cottage group is more heavily altered than others in the area but retain a rural charm

Fig. 55: Taller terrace at the western edge of the Conservation Area

Architecture

Although there is a high degree of variation within the Conservation Area, there are general townscape features which are relatively consistent. The area is predominantly residential except for one shopfront (No. 92 Queen’s Road), being consistent in height and scale.

Dwellings range from 2-3 storeys with a mixture of yellow and gault brick prominent. Front gardens with bay windows on the ground floor are predominant and a constant feature in all the streets.

Victorian terraced houses, with doors set in pairs, are predominant on Queen’s Road. Their steep-pitched roofs, forward-facing gables, angled bay windows, and parapet above are distinguishable and well-preserved. Some Edwardian houses have mock timber gables and prominent chimneys sited down the slope of the roof.

Less commonly, cottages are a reminder of the rural history of Twickenham with two storeys, stock brick and red dressings. Numbers 29 and 31 Holly Road are statutorily Grade II listed buildings; both are a pair of cottages built mainly of brown brick in a Flemish band with red brick headers but heightened in stock brick.

Although the quantity of statutorily listed buildings is low, numerous buildings are designated as Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) due to their important architectural and historic features that are worthy of preservation.

Spatial Analysis

The general spatial character of the Area is that of an open, residential suburban development, established through the inclusion of good-sized front gardens and gaps between groups or pairs. The height and layout of built forms are consistent, and gaps often indicate a transition in period or style. The slight curvature of the roads prevents a sense of enclosure, instead offering slightly changing views and invitation to explore what lies beyond. Houses typically have large back gardens so there are not often views toward other development except for the taller buildings along King Street and the few examples of newer, taller development to Grosvenor Road. The few examples of back land development are accessed via narrow alleys or mews, which have a contrasting character to most of the area and are reflective of their industrial origins.

Townscape and Architectural Details

Open Spaces, Gardens & Trees

The Conservation Area is absent of street trees, and instead, its leafy garden character comes from well maintained front gardens with a variety of planting types, including mature trees. Garden depths vary, but all residential properties have at least a small front garden. Full hard landscaping has resulted in gaps in the streetscape and the introduction of an overly urban character, which is unsuitable and undesirable, and should be avoided. When combined with the loss of a boundary wall, the harm is even more apparent.

The only public open space in the Area is the Holly Road Garden of Rest, which offers an escape from the adjacent busy town centre and contributes to the spatial character of the Area. Its mature trees are visible along the route of Holly Road and help screen the bulk of Queen’s House beyond.

Windows

Windows are typically timber sash with either a single or no glazing bars, and a good number of historic windows survive in the Conservation Area, alongside sympathetic replacements. Where casement windows have been used, the survival is more mixed, with replacements having thicker plastic frames and windows that are not flush with the frame. Unfortunately, the cottage groups have a more mixed presentation of windows, with unsympathetic casement windows introduced or replacement sash windows which are overly reflective or have discordant glazing bar patterns.

Doors and Entrances

Door styles vary greatly throughout the Conservation Area, but even where originals are lost, are often reflective of their host dwelling. Many good examples do survive, however, and replacements have been informed by other houses in the group of the same typology. The long western group to Queen’s Road has a distinct design of two lower panels with an arched window to the top half. The gothic and Italianate groups at the north side of Queen’s Road have unique doors which are reflective of their host dwellings’ more intricate designs. To the cottages and other dwellings, doors tend to be of a simpler design, often four or six panel doors, with four being more accurate to their Victorian origins.

Porches are common, either inset into brick arches or rendered pediments, while some Edwardian houses have more delicate projecting timber porches with slate roofs. The porches add depth to the façades and are often paired with contrasting projecting elements such as bay windows, contributing to an interesting and varied streetscape.

Many houses have raised front entrances which are accessed by simple stone steps, with low brick walls, generally capped in decorative brick or stone. Render and rails to these walls are uncommon. Where the stairs do not rise immediately from the pavement, there is little consistency in the treatment of footpaths leading to them.

Fig. 56: The Edwardian group have simple porches and a good amount of historic doors survive

Fig. 57: A pair of doors set back in the same terrace

Fig. 58: This gothic terrace has deeply inset porches and the original ornate doors reflect the style of the host dwellings

Fig. 59: Another door typology to Queen's Road, the upper gorund floors accessed by simple stairs generally with low walls between

Roofs

Roofs are generally gables to terraced properties and hipped to semi-detached and detached houses, most often finished in slate or pantiles. Where modern slate alternatives have been used, these are overly shiny and smooth and starkly contrast to the weathered and natural slate. Interventions into the roof are very uncommon, primarily restricted to rooflights which are few and set high into the roof slope. Historic dormers and front gables add variety and interest to the streetscape but are consistent and balanced within groups.

Fig. 60: Simple gable roofs are common throughout the area to various building typologies

Fig. 61; The roofscape is consistent amongst groups and there is generally little alteration to roofs in the Area

Fig. 62: Gable detail to the Edwardian terrace group

Boundary Treatments

Boundary treatments are varied in their design and appearance but there is consistency in their material and scale which contributes positively to the streetscape. To Queen’s Road, boundary walls are typically low brick with slightly taller brick piers, often finished in the same colours as the host dwelling. Some walls are very low, revealing front gardens, but where this is combined with paved front gardens, contributes to visual gaps and an overly urban appearance. Rails above low walls are uncommon and not characteristic of the area. Traditionally, timber fences would have been the most common, and there are a few quality examples or modern replacements still to be found.

Boundaries are consistently low and transparent, so that front gardens are easily observed, creating a sense of openness and contributing to a suburban spatial character, where longer views are possible across multiple gardens. Some boundaries have used hedges for privacy, but these appear too formal and create a barrier which blocks views towards the house, detracting from the open character of the area and disrupting the streetscape. Privacy screening should instead be achieved through a rich variety of types and heights of plants, which will change seasonally and still allow glimpsed views into gardens.

To Grosvenor and Holly Roads, timber fences are the most common boundary treatment which is reflective of the different building typologies. Some have been replaced with brick, which while proportionate and of a matching material, is at odds with the appeal of these domestic dwellings.

Fig. 63: Cottages would have had simple timber boundaries, mostly replaced with 'picket fence' style

Fig. 64: Both timber and brick are common boundary treatments, This timber boundary is more akin to original simple forms, while low boundaries are complimented by garden planting, although hedges can restrict views into front gardens

Fig. 65: Low brick boundary wall with low hedges which allow greenery and maintain views into gardens

Paving

The entrance to the Conservation Area via King Street is finished in high quality pavers and granite kerbs, which were replaced as part of a wider improvement scheme to primarily within the Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area. There are attractive setts surviving to Messom Mews, reflective of the historic works which once operated here, but otherwise the paving in the Conservation Area is unremarkable, failing to reflect the quality and attractiveness of the built environment.

Fig. 66: Contemporary paving to the entrance from King's Road, laid as part of a wider upgrade to King's Road / the commercial centre

Fig. 67: Good quality pavers are present at the south end of Queen's Road, and granite kerbs can be found throughout

Fig. 68: Herringbone brick pattern to the car park

Fig. 69: Historic setts preserved in situ to Messom Mews

Street Furniture

Street furniture is scarce given the primarily residential nature of the Conservation Area, primarily in the form of streetlighting and parking/street signage. Lamp posts are either of a standard municipal appearance of green poles with flat grey lanterns or, to Holly Road, slightly more decorative black poles with orb lights.

Fig. 70: More decorative lamp posts can be found along Holly Road

Fig. 71: Standard posts are found elsewhere in the Conservation Area

Part Three: Management Strategy

Summary

The Appraisal has assessed the quality and the condition of the Queen’s Road Conservation Area. Several site visits were undertaken between August and October 2022, when the area was observed and photographed.

This Appraisal has summarised the strengths and weaknesses of the area and this management plan will set out a strategy to consolidate and enhance these strengths and prevent further erosion of the area’s special historic and architectural character.

The Conservation Area is well maintained, and it is hoped that this clearer, more extensively illustrated Appraisal will assist the Development Management process in making more informed planning decisions in respect of the Area’s character. It will also assist applicants to ensure their proposals contribute positively to the preservation or enhancement of the Conservation Area.

Under section 71 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 local planning authorities have a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of Conservation Areas in their area from time to time. Regularly reviewed Appraisals, or shorter condition surveys, identifying threats and opportunities can be developed into a management plan that is specific to the Area’s needs.

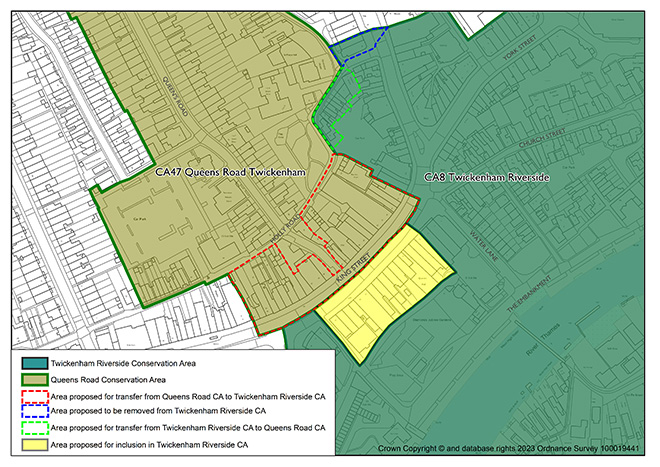

Boundary Changes

This Appraisal has also identified areas where boundary changes/extensions would be suitable, to include buildings of some architectural and historic quality which have a shared character and appearance to the existing conservation area, and to rationalise existing conservation area boundaries into more coherent groups.

Transfer of North Side of King Street from Queen's Road Conservation Area to Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area

It is considered that the north side of King Street (Nos. 10-62, even) has a more commercial and urban character that is more closely aligned with the character and appearance of the Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area, and therefore it is proposed to change the boundary to transfer these addresses. Similarly, the addresses along Holly Road which were previously part of the Queen’s Road Conservation Area, are proposed to be included in Twickenham Riverside. Although these buildings address Holly Road, their character is of back land/outbuilding development to the more prominent commercial buildings of King’s Road, and therefore have a stronger connection to this character and appearance. The buildings to be excluded from the Queen’s Road Conservation Area and instead moved to the Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area are: 29-35 (odd), 90A, 50-67 (odd) Holly Road

Transfer of group to east side of Holly Road from Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area to Queen's Road Conservation Area

Similar to the proposed amendment of the boundary above, it is considered that the group of buildings at the east end of Holly Road has a smaller, more domestic character which is more aligned with the development, character, and appearance of the Queen’s Road Conservation Area. Therefore, this group of buildings is proposed to be transferred from the Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area and a new boundary formed to include them within the Queen’s Road Conservation Area. The addresses to be included are: 1, 5, 13-27 (odd) Holly Road.

Problems and Pressures

- Loss of traditional architectural features and materials due to unsympathetic alterations

- Loss of front boundary treatments and front gardens for car parking

- Lack of coordination, clutter, and poor quality of street furniture and surfacing

Opportunity for Enhancement

- Preservation, enhancement, and reinstatement of architectural quality and unity

- Retain and enhance front boundary treatments and discourage increase in the amount of hard surfacing in front gardens

- Coordination of colour and design, rationalisation, and improvement in quality of street furniture and flooring

- Improve the setting of the Albany PH on the Station Yard frontage, with paving improvements and possible tree planting.

Design Guidance

Historic England recommends that the Appraisal is also a source of guidance for applicants seeking to make changes that require planning permission, helping to make successful applications.

The guidance below will set out design guidance which encourages good quality design, which will help to both preserve and enhance the character and appearance of the Conservation Area.

Dwellings within the Conservation Area which are blocks of flats do not benefit from Permitted Development Rights, requiring planning permission to carry out alterations and extensions.

Windows

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace, so it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. In Georgian and early-mid Victorian terraces, each half of the sash was usually wider than it was high, but its division into six or more panes emphasised the window’s vertical proportions. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed a simpler pattern, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar.

Many original timber sliding sash windows survive within parts of the Conservation Area, and these make an important contribution to the special character and appearance. However, some have been lost and many replacements are of a different style and materiality which is unsympathetic to the historic appearance of the building and conservation area, disrupting the harmony and rhythm of the legible groups, particularly cottages, and creating inconsistences within the otherwise congruous terrace typologies.

The quality of these replacements also varies, which dilutes the consistent appearance of the building groups, with some mimicking historic style while others are inappropriate uPVC and casement windows. Where timber sashes have been replaced, these are often of poor quality, with thicker frames and higher reflectiveness, varied horn details, a variety of glazing bar formats, and there is an emerging lack of consistency to the approach to fenestration.

Residents are encouraged to, in the first instance, retain and repair existing original timber sash windows. If replacement is required, all aspects of the window should be considered including opening type, glazing bar pattern, horns to sashes, and depth. Windows should be timber sash and are generally single panes with no glazing bars or a simple two-over-two. Timber frames are not only the most appropriate option, but a natural material which helps reduce the use of single-use plastics, often found in other windows. Timber windows also have the benefit of being more cost effective, being much more durable and repairable than alternatives, and there are options to maintain their appearance while introducing energy saving and noise reducing features.

Single glazing is the most common approach and would be the most acceptable replacement to maintain the existing character and appearance of the area. Secondary glazing is an unobtrusive option to increase efficiency, reduce noise, and avoid intervention to existing fabric, often performing as well, and lasting longer than double glazing. Double and triple glazing can be inserted into timber frames and help maintain a consistent appearance with similar benefits to secondary glazing and may be appropriate where there is justification for full replacement. Where double/triple glazing is accepted, black spacing bars and seals should be avoided – these should instead be white to blend with the frame. Trickle vents should be avoided or well concealed within the frame to maintain consistency with historic appearance.

Windows to contemporary development can vary in detail but it is still important to consider their design in relation to the character of the area.

Doors

Like windows, it is encouraged that residents, in the first instance, retain and repair any existing original timber doors. This is best for the environment, for the character and appearance of the area, and is often a more inexpensive solution than complete replacement. Simple modifications can often be carried out internally which improves the weatherproofing of the door without impacting its external appearance.

If a replacement is required, then it should match the original door for the property. There are many good examples of surviving doors which vary in design but generally reflect the typology and architecture of the host dwelling/group. Typically, doors are simple timber four panel doors to Victorian buildings, and six panel doors to Georgian.

There is a prevalence of door furniture within the Conservation Area, particularly to the more decorative dwellings of Queen’s Road, such as decorative door knockers, letter flaps and doorknobs.

Roof Extensions

Roof extensions are uncommon and the consistently unalterated and varied roofscape makes a key contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. Hipped roofs remain unaltered and contribute to important spaces between semi-detached properties. There is a limited example of rear dormers which are effectively employed given their small scale and ability to be well concealed from the public realm.

Gardens

Front gardens make a positive contribution to the landscape setting of houses and add to the leafy suburban character of the Conservation Area. Consistent, well planted front gardens can also unify streets and soften their overall appearance. Full hard-surfaced frontages are generally uninviting and lessen the separation between the public and private realm, compromising the intended setting of the built environment. For these reasons, along with environmental and ecological reasons, they should be avoided.

Glimpsed views between houses to rear gardens and mature planting help break up the street scene and contribute to the overall suburban character.

Boundaries

Boundary treatments vary throughout the Area, but a good degree of consistency remains to groups, such as the workers’ style cottages where simple timber fencing is reflective of the simple domestic architecture. Queen’s Road is generally more mixed with low brick walls with piers. Brick walls should be reflective of their host dwelling, and not so tall as to restrict views into gardens, which creates an uncharacteristic appearance of enclosure. Rails are uncommon and unsuitable to the housing typologies found within the Area.

Lightwells

Where sufficient garden depth allows, lightwells can be discreetly inserted and should be flush with the ground and be cited following best practice as well as policies in the Local Plan. Where lightwells are accepted, they should not be paired with full hard landscaping, but rather mitigated with soft landscaping elements, such as low maintenance shrubbery.

Painting and External Finishes

Painting is uncommon and is generally discouraged as it can alter an otherwise uniform character of the area. It should only occur if the existing property has already been painted, and an appropriate colour should be selected to maintain the overall neutral palette of the Conservation Area. Most often existing colours should be refreshed, or neighbouring houses can be referenced to create a harmonious appearance.

External finishes are not a common feature to the Conservation Area, and the approach to their treatment is similar to paint – existing finishes can be repaired and restored, and new finishes not normally approved. The predominant character of the area is derived from the consistent use of brick, while details may be in contrasting brick, render, or less commonly finished in another material.

Energy Efficiency

Introducing energy efficient measures is desirable to reduce carbon emissions, fuel bills, and improve comfort levels. It is important that the appropriate course taken should be informed by the context of the building being improved, with each building having different opportunities and restrictions. Not all solutions will be appropriate across the conservation area, and the ‘Whole Building Approach’ advocated by Historic England encourages a case-by-case approach, which fundamentally considers the context, construction, and condition of a building to determine which solutions would be the most suitable and effective. More detailed advice can be found within the Guidance Note Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings: How to Improve Energy Efficiency 2018.

Solar Panels

Solar Panels and equivalent technology are most suitably placed on rear or side elevations where they are hidden from the public realm – principal elevations and roof slopes facing the public realm are less appropriate as they generally make the most substantial contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. New technologies, such as PV panels disguised as slates and sitting flush with roof materials, may be suitable in the appropriate context, and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.