Twickenham Riverside

Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation Area No.8

Contents

Part One: Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principal aims of conservation area appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications.

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication titled Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’.

The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to local conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan and national policies of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

Our overarching duty which is set out in the Act is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

conservation_areas_spd.pdf (richmond.gov.uk)

Buildings of Townscape Merit

Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) are buildings, groups of buildings or structures of historic or architectural interest, which are locally listed due to their considerable local importance. The policy, as outlined in the Council’s Local Plan, sets out a presumption against the demolition of BTMs unless structural evidence has been submitted by the applicant, and independently verified at the cost of the applicant. Locally specific guidance on design and character is set out in the Council’s Buildings of Townscape Merit Supplementary Planning Document (2015), which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

buildings_of_townscape_merit_spd.pdf (richmond.gov.uk)

Designation and Adoption Dates

Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area was designated on the 14th January 1969.

It was subsequently extended on the 7th September 1982, and the 29th January 1991.

Following approval from the Environment, Sustainability, Culture and Sports Committee on 17th January 2023, a public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between 17th March and 28th April 2023.

This Appraisal was adopted on 20th November 2023

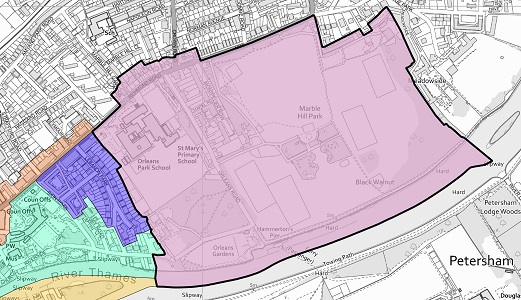

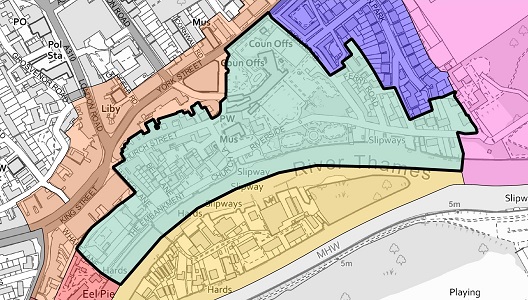

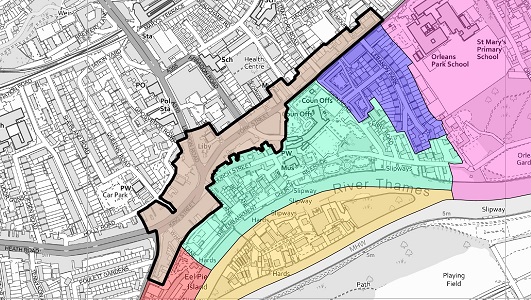

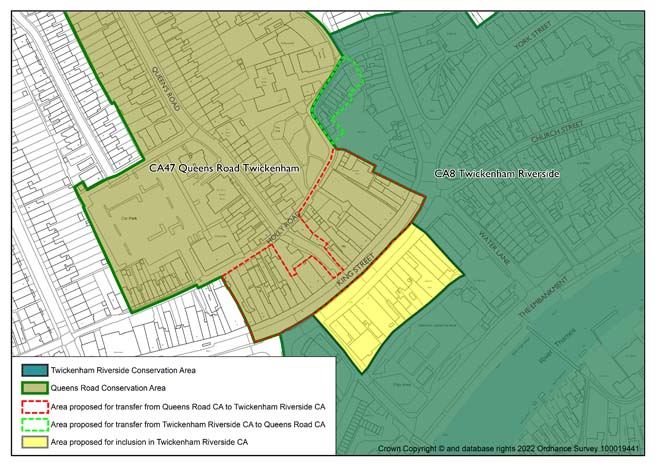

Map of Conservation Area

Statement of Significance

The significance of the Conservation Area is intrinsically linked to its relationship with the Thames and the evolution of the quayside village into a bustling and prosperous town centre. At its core, historic remnants of the former village remain obvious, including deep and narrow burgage plots surviving from medieval times, and dense, traditional laneways branching from busy main roads. There also remain pockets of small-scale domestic dwellings, such as simple workers' cottages reflective of the contrasting character between the village centre and the grander developments along the river’s edge, which once enjoyed the status of summer retreat for many prominent figures, such as Alexander Pope. The relationship with the river remains prominent, with surviving light industrial works, slipways and boathouses making an important contribution to the Area’s character, as well as the unique charm of Eel Pie Island. Primarily a historic town centre, the piecemeal and organic growth of the area has resulted in a richly varied and much altered townscape, and the character of much of the area is defined by this diversity and a richness of building typologies.

Historical Development

Stages/phases of historical development and historic associations (archaeology etc.), which may be influencing how the area is experienced.

Archaeology

Pottery and flints discovered in a Church Street dig of 1966 date from 3000 BCE and provide the first evidence of humans in Twickenham. The riverbed between Eel Pie Island and Twickenham has produced other important finds. Evidence of the Roman occupation has been provided by a number of scattered archaeological finds.

Saxon and Norman Twickenham

The Domesday Book of 1086 does not mention Twickenham individually because it formed part of the Manor of Isleworth, but it is estimated that Twickenham consisted of approximately 25 households. During the 11th century the population grew, and Twickenham expanded; the village was centred around the church, extending in a linear form along Church Street and King Street with narrow lanes running down to the riverside. Archaeological excavations at the rear of 29 and 31 King Street revealed medieval rubbish pits, probably associated with buildings at the western edge of the settlement. A church is thought to have been established on the site of the present St. Mary's church by the end of the 11th century. The oldest part of the present church is the stone tower which dates from the 14th century, the nave of the same date fell into serious disrepair and finally collapsed in 1713 (later rebuilt by John James, the architect of Orleans House).

15th, 16th, and 17th centuries

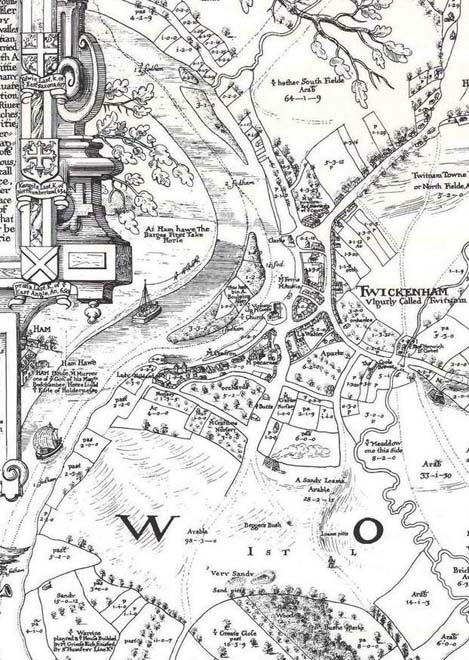

The manor of Shene (Richmond) had been transformed into a royal palace during the 15th century by both Henry V and Henry VI. This coupled with Henry VIII's development of Hampton Court into another fully fledged palace in the early 16th century, had an enormous impact on Twickenham which lay between the two. Courtiers, poets. painters and nobles associated with the royal household began to build fashionable houses along the Thames as summer and weekend retreats from the increasingly noxious City of London. The map of 1635 by Moses Glover (Fig.1) clearly shows the Thames and Eel Pie Island and the street pattern, much of which survives today.

18th century onwards

The concept of a villa set in a natural landscape as a classical retreat for the cultivated man emerged in the first decades of the 18th century and ultimately formed the basis of the English Landscape Movement epitomised by the work of Launcelot 'Capability' Brown. The decision of Alexander Pope, the poet and satirist, to move to Twickenham was of great importance. He leased a property in Cross Deep from 1719 which he adapted and extended, with architectural advice from Lord Burlington, to create a classical villa facing the Thames. Pope lived in the villa until his death in 1744 taking great pleasure in the laying out of the grounds with professional assistance from William Kent and Charles Bridgman. Cross Deep separated the house from its riverside gardens, so Pope built an ornamental grotto under the road to act as an ingenious link. The villa was eventually demolished in 1808 but the grotto survives lying beneath the science laboratory of the present-day school.

In this spirit, a perfect new Palladian villa called Marble Hill was built between 1723-9 for Henrietta Howard, Countess of Suffolk. The elegant, white villa was set in a purpose-built riverside garden designed by Pope and Bridgman. In 1887 the house was bought by the Cunard family who planned to demolish the house and develop an estate of suburban houses on the grounds.

There was uproar locally, especially with regard to the impact on the famous view of the Thames from Richmond Hill. Fortunately, in 1902 the house and grounds were saved by a consortium of local authorities and private donors for public use and enjoyment and are now in the care of English Heritage. As a result, the Richmond, Petersham and Ham Open Spaces Act was passed in 1902, which in conjunction with various covenants, was designed to protect views and prevent building in some areas.

Orleans House was designed in 1710 by the architect John James for James Johnston, a Scottish politician. The Octagon was added in 1718 and was designed by the architect James Gibbs. The house only acquired its present name in 1815 after Louis Phillipe, Duc d'Orleans stayed there. By the late 19th century Orleans House became the property of a gravel company who demolished most of the house. The remnants of the house included The Octagon and were bought by Mrs Basil lonides when she bought the adjacent Riverside House. On her death she bequeathed her riverside properties to the local authority and the Octagon now forms the central feature of Orleans House Gallery.

The opening of Richmond Bridge in 1777, connecting Richmond directly to Twickenham for the first time, dramatically increased traffic through Twickenham. The arrival of the railway in 1848 signified the end of Twickenham's era as a suitably quiet location for grand riverside villas. Large estates started to be broken up and sold off as plots for speculative housing to accommodate the expanding ranks of middle-class commuters. Between 1801 and 1901 the population increased dramatically from 3000 to 21,000. By the end of the 19th century, Church Street had become a pinch point between Richmond and Twickenham. It could not be widened so a new road, York Street, was created in 1899; older properties were demolished, and the ancient street plan altered. Further road widening in 1928 saw the demolition of the south side of King Street, and the construction of new shopping parades, creating a shift in commercial focus from the river to the town centre.

Fig. 1: 1635 Map of Twickenham, Moses Glover

Fig. 2: John Rocque's London 10 Miles Round Map, 1746

Fig. 3: Samuel Lewis Map, 1784

In 1926 Twickenham became a Borough, acquiring York House as an acting Town Hall. The borough was enlarged 1937 to include the neighbouring districts of Hampton, Hampton Wick and Teddington. In 1965 the Borough was in turn united with Richmond and Barnes to form the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.

Fig. 4: Aerial view of Twickenham, 1928

Eel Pie Island

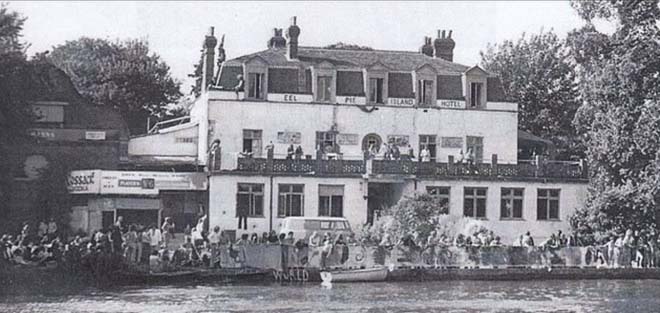

Fig. 5: Eel Pie Island Hotel

Early maps show that Eel Pie Island was originally 3 separate islands, which became two and subsequently one. The eastern and western wooded ends were originally separate islands and were also susceptible to flooding which is why they have remained uninhabited to the present day. The island has been known by a number of different names including Twickenham Ayte, Goose Eyte, and Parish Ayte. Licensed premises are recorded as early as 1743, and by 1786 an inn known as the White Cross was well established. It was replaced in 1830 by a much grander building renamed the Island Tavern. It proved to be a very popular spot for boat trips and excursions and the visitors readily consumed the eel pies which were part of its fare. By the mid C19th it had become known as the Eel Pie Tavern and the island took its current name.

Fig. 6: Eel Pie Island and The Embankment, Twickenham, 1928

By 1893 the appearance of the island had changed dramatically with the establishment of boatyards, the construction of the Twickenham Rowing Club boathouse and a ferry operating between Water Lane and the island. The construction and completion of the Richmond

Lock and weir in 1894, enabled Eel Pie Island’s riparian services and activities to flourish and

continue to flourish with a navigable level of water, even at low tide In 1899 the hotel was sold and some of its land was auctioned off as lots for development as private homes or as businesses. As the C20th progressed the popularity of the hotel declined steadily as tastes changed. By the 1950s the hotel found a new lease of life as a jazz club and was successful enough for the owner to fund the construction of the footbridge (opened 1957) linking the island to Twickenham. The hotel continued to attract young people with the appearance of fledgling pop groups like the Rolling Stones. Sadly, by the late 1960s the hotel was empty and fell into disrepair and after a fire it was demolished in 1971.The site was redeveloped with modern townhouses.

Fig. 7: Boathouses on Eel Pie Island, date unknown

Archaeological Priority Areas

An Archaeological Priority Area (APA) is an established location where there is strong known archaeological interest or a particular potential for future discoveries. The local plans for the London boroughs describe APAs. They provide guidance for putting national and local planning principles into practise so that archaeological interest is recognised and preserved.

Historic England updated the Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal for the London Borough of Richmond in March 2022: London Borough of Richmond Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal

The Greater London Archaeological Advisory Service completed its review and update of the boroughs Archaeological Priority Areas in 2022. This identifies the area as encompassing the Tier 2 areas of Marble Hill (2.14) and Twickenham and Riverside (2.17). https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/planning/apa-richmond-upon-thames-2022-pdf/

Part Two: Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Setting

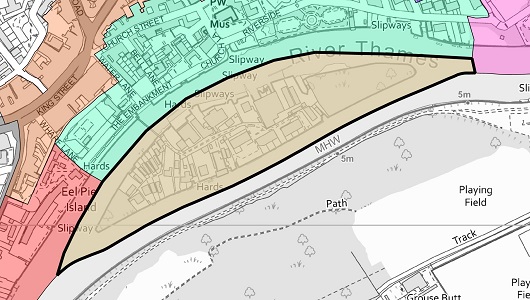

The Conservation Area is situated on the Middlesex bank of the River Thames and spans from Marble Hill Park in the east to Radnor Gardens at its western boundary, with the A305/A310 forming most of its northern boundary. To the south, the Conservation Area extends south into the Thames to include Eel Pie Island, which is physically connected via a narrow footbridge. It is surrounded by a number of other conservation areas such as Richmond Hill to the east, Amyand Park Road to the northeast, and Queen’s Road to the northwest.

Sandwiched between the river and the principal road to Richmond, both landscape and townscape have been determined by the proximity of the River Thames. A double curve of the river gives continuing unfolding views of both banks framed by mature trees and foliage. Although outside of the Conservation Area, Ham Lands to the south form an important part of the Area’s setting, contributing to its natural/rural/village character.

Topography

The Conservation Area is relatively flat though it does rise gently to the West and slope slightly toward the river at its south end, with some slipways remaining between Sion Road and Lebanon Park. Much of the riverbank, however, has been built up and so the river itself sits below the embankment.

Buildings and Townscape Overview

The layout of the Conservation Area, and thus its appearance and how it is experienced, is dominated by two routes: the curving course of the Thames, and the parallel roads of York Street/Richmond Road, King Street, and Cross Deep.

These busy roads shifted the historic core and focal point of the historic village and have influenced both the layout and type of development, with the most dense, urban character at the junction of the main arterial route with London Road and the historic Church Street. Outside this core, many historic properties turn instead to address the river, and it is along its frontage that the most significant developments can be found.

Within the centre of the village, historic remnants remain obvious, including deep and narrow burgage plots surviving from medieval times, and dense, traditional laneways such as Church Street which project from the busy main roads. There also remain pockets of small-scale domestic dwellings, such as simple workers’ cottages reflective of the contrasting character between the village centre and the grander developments along the river’s edge. Primarily a historic town centre, the piecemeal and organic growth of the area has resulted in a richly varied and much altered townscape, and the character of much of the area is defined by this diversity and a richness of building typologies.

With the arrival of the railway, as with many areas in London, development was spurred and the type of occupant relocating to Twickenham shifted. In response, large sections of land from former estates were sold off for speculative development – most evident in Lebanon Park. This area illustrates an important shift in the evolution of the area and has a more obvious and consistent townscape than the other character areas which will be examined in this Appraisal.

Although there is a high degree of variation within the Conservation Area, there are general townscape features which are relatively consistent.

Commercial buildings range from 2-4 storeys, where the top storey is often contained within a pitched or mansard roof, and occasionally behind a parapet. Fourth storeys are typically set back or most often articulated by way of decorative projecting gables. Frequently, corners are addressed, often with architectural elements such as projecting corner elements or narrow corner façades.

Shopfronts are restricted to the ground floor, most commonly within a single building or bay, but increasingly occupying the entire ground floor of a smaller terraced group. Often the wider shopfronts are visually subdivided to reflect bays, but some contemporary shopfronts fail to achieve this. Shopfront styles overall are varied, but there are a number of surviving historic shopfronts in good condition, and contemporary shopfronts are generally of a good quality, following traditional forms, proportions, and detailing.

Residential dwellings are typically 2 storeys with simple pitched or hipped roofs, and roof alterations are uncommon. In areas such as Lebanon Park, houses are designed with the appearance of two storeys while offering a habitable third storey.

Victorian houses are generally short groups of terraced workers’ cottages, but there is rich variation, with earlier mews style housing to Orleans Road in various configurations, semi-detached homes in Lebanon Park, taller Georgian townhouses on Montpelier Row, and more robust detached villas to Cross Deep.

Brick is the predominant building material, with stock and gault brick generally employed for residential use and red brick for commercial buildings. Even where this norm is broken, such as in Lebanon Park where there are red brick façades, lower cost stock brick is utilised to secondary elevations. Paint and render to entire elevations are uncommon.

Embellishments are frequent, and a variety of materials used, most often differently coloured brick, or stone or rendered features.

Institutional buildings, such as churches, banks, and civic buildings, are also often constructed of brick, which is somewhat atypical and adds to the rural character of the Conservation Area, though these buildings often utilise robust stone elements to elevate their status.

Despite the rich variation of the area, there are legible groups, or sub-areas, which have a shared character and history and are outlined in further detail below. Within each broad area there are further subdivisions, reflecting the complexity of urban development and variations in the overall character.

Spatial Analysis

As the Conservation Area is focused along two main routes, much of it is experienced in a linear fashion, often to the disadvantage of its proximity to the Thames. Along its northern boundary, the Area is primarily experienced following the main busy roads, built up on each side, giving a sense of an enclosed urban centre, a sense which dissipates at each end where there is a more residential and suburban character, with large houses and front gardens becoming more common. The gently curved road offers shifting views as one travels along it, informed by the course of the river, and the forks in the road at Cross Deep to the west and London Road/York Street/Church Street to the east invite the eye and exploration. Although there are side routes which offshoot from the main throughway, the buildings at corners generally do not reduce in scale, and therefore there is little impression of breaks in the consistent streetscape.

To the south of the Conservation Area along the embankment, there is a clearer sense of openness with the Thames – development is typically set back from the road with the promenade and Thames Path offering pedestrian access, although the presence of cars detracts from this. Radnor Gardens and the Thames Path at York House Gardens offer a more tranquil and open view of the river, and their positions allow for interesting views through much of the Conservation Area’s boundary and its changing character, including towards Eel Pie Island.

The historic centre feels perhaps more enclosed due to the narrowness of its streets, but the side lanes, such as Water, Bell, and Church Lanes offer longer views toward the river, contributing to a village character.

Lebanon Park has a good established layout, and while the development is consistent and somewhat linear, the reasonable front gardens and gaps between buildings prevent an overbearing sense of enclosure. The side roads, slight curve, and forking of Lebanon Park also break the traditional grid form and give the impression of a neighbourhood more than a typical row of Victorian terraces might do.

Marble Hill is the largest open space in the Conservation Area, with a distinct rural feel in contrast to the suburbanised setting and town centre of Twickenham beyond. Within this area, there are pockets of enclosure created by mature planting and historic brick boundary walls, but primarily it is experienced as open parkland. Orleans Road and Montpelier Row have their own townscape, which is contemporary to the park.

The Conservation Area generally slopes toward the river which allows for evolving views toward the river and Eel Pie Island from the centre, while taller building elements, such as the church tower and the top of the Civic Centre, are visible in longer views from the embankment, and particularly from the footbridge to the island.

Traffic is a dominating feature of the Conservation Area and greatly impacts how it is experienced and perceived. Much of the Conservation Area is focused on the A-roads which pass through the area and influenced its development, their introduction altering the ancient street plan. King Street, therefore, has a more open feel than the adjoining roads, though this openness is impacted by traffic. Increased traffic creates a sense of separation, both visually and physically, which has affected the quality of the urban fabric and public realm, while the resultant noise and pollution has impacted air quality and makes the area less attractive to pedestrians and cyclists. The infrastructure required for traffic has also greatly influenced the layout and development of the area. Traffic creates an ever-changing spatial element and contributes to a contrasting character between the commercial centre and relative tranquillity of the other character areas.

Townscape Details

Here, general townscape details which are consistent throughout the Conservation Area will be highlighted – where elements are more distinct to a character area, they will be further addressed within the sub-section below.

Hard Landscaping

Footways are for the most part high quality York stone pavers with granite kerbs, and the quality of the material is reflective of the high quality of the urban character. In some places, lesser quality concrete pavers have been used to a similar effect. To peripheral streets, brick is often used for pavements in a simple running bond, in various qualities and colour of brick, though typically in purples or greys. Within the historic core, to verges, there are good surviving examples of granite setts, which are reflective of historic street patterns and add richness to the character of the area.

Fig. 8: Wide pavers with granite kerbs

Fig. 9: Smaller pavers inserted primarily along King Street as part public realm improvements

Fig. 10: Bricks in herringbone pattern appear sporadically

Fig. 11: Common square pavers

Trees and Soft Landscaping

Street trees are uncommon, apart from within Lebanon Park, and yet a rich green landscape persists in much of the area, formed by richly planted private gardens, grounds, and pockets of greenspace, as well as the large parks which form a substantial part of the Conservation Area as a whole. The river front in particular is very green with a promenade of trees, the Gardens at Radnor, York House, Orleans Gardens, and Marble Hill, as well as Eel Pie Island which is lush with vegetation. The sense of greenery is enhanced with the views toward Ham on the other side of the river, where the bank is lined with mature trees.

Fig. 12: Street trees are primarily found near residential development, such as here in Lebanon Park

Soft landscaping is underutilised, and the occasional potted plant and hanging basket to the commercial centre. Soft landscaping is most utilised at the Embankment, where it separates the pedestrian area from parking and surrounds garden walls.

Street Furniture

Lamp columns are generally of two styles – within the commercial centre, they are black columns with decorative lanterns, while to the peripheries they are more modern, green columns with a flat grey lamp. Where space does not allow for a post, the decorative arm and lamp are sometimes attached to the façade of a building to allow the pavement to remain clear of obstruction

Bike stands are few but of typical Sheffield style in black.

Bollards are generally black iron – within the commercial centre, they are connected by vertical poles at curves in roads acting as a visual and physical barrier, guiding traffic through and separating pedestrian areas.

Fig. 13: More decorative lampposts appear along busy roads and paths

Fig. 14: Most other lampposts are of a standard design common in the borough

Architecture

The evolutionary character of town centres, shifting to reflect and meet the needs of its occupants, results in a complexity of urban development and variations in their overall character. While this document identifies sub-areas that have a more obvious and legible shared character and appearance below, this section will broadly outline common styles, materials, and features, which are evident and relatively consistent throughout the Conservation Area. Given the variety of the area, the descriptions are not exhaustive, and where clear variations exist, these will be addressed within the appropriate character area descriptions.

Community Buildings – Civic buildings and places of worship are concentrated in the centre of the Conservation Area, which is reflective of its village origins. These buildings are often set back and within formally planned spaces, but given the density of the area, they do not cause disruption to consistent streetscapes or building heights. The status of these buildings is typically illustrated by their larger scale and use of building materials, frequently employing stone or terracotta for architectural embellishments. Buildings such as banks also employ more robust building materials and are typically of a larger scale, and often anchor corners or parades.

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace or semi-detached pair of houses. The Conservation Area contains a wide variety of window styles, and many unsympathetic replacements but it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. In Georgian and early-mid Victorian terraces, each half of the sash was usually wider than it was high, but its division into six or more panes emphasised the window opening’s vertical proportions. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed a simpler pattern, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar. Windows reduce in size and have simpler surrounds as they rise through the building demonstrating the hierarchy of the internal spaces.

Window frames are most commonly white painted timber, and where uPVC replacements have been allowed, these are mostly white and reflect the historic glazing pattern. Both casement and sash windows are common, reflecting the Victorian and Edwardian periods from which most of the buildings date.

Bricks are the most common building material within the Conservation Area, with residential properties primarily comprised of stock and yellow brick, while commercial premises are generally red brick. Public buildings are also generally constructed of brick, including churches and schools. Brick is also often used in contrasting colours as a decorative embellishment.

Later development has also employed brick skins, generally paired with contemporary windows and detailing, such as metal window surrounds, which respect historic proportions and the rhythm of the existing streetscape but remain legible as later additions.

Roofs are most commonly finished in black slates or red tiles. Roof extensions or alterations are uncommon, with few examples located to commercial buildings. Where commercial premises have been altered, this has been carried out through mansard style roof extensions, generally in slate, set back from the parapet, or through simple, consistent dormers into the existing roof slope.

Character Areas

Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area is one of the largest and most varied in the Borough. For ease of appraisal, it has been divided into the following sub-areas each with its own distinct character:

- Marble Hill & Orleans

- Lebanon Park

- Historic Centre and Riverside

- Eel Pie Island

- Commercial Centre

- Cross Deep

Character Area 1: Marble Hill and Orleans

Fig. 16: The Character Area is centred on the grounds of Marble Hill House

Summary Description

Marble Hill House and Park form a substantial portion of the eastern section of the Conservation Area which is characterised by its open space. The 18th century Montpelier Row and Orleans Road are contemporary, and little change to the character and general form of the area has occurred since this period other than the park transferring to the public realm.

Character Appraisal

Townscape

Marble Hill and Orleans House & Gardens

The distinguished greenery and spacious character of Marble Hill Park (Grade II* Registered Historic Park & Garden) is visible from many points in the area, providing its characteristic parkland atmosphere. From the edge of the Conservation Area, at Richmond Road, the park is observed through a thin line of trees, separated from the public realm by a simple timber fence. At the west side of the green is a simple late 18th or early 19th century single storey lodge building (Grade II), a remnant of the private estate, while to the east is a short access route leading to a small car park adjacent to 20th century development. Beyond the border lies an expanse of grass, currently in use as a cricket field, and at its centre, in the distance, the landmark building of Marble Hill. The Grade II* Palladian villa lies at the centre of the park, with expansive lawns surrounding. The lawn is edged on the north and west boundaries by the remnants of the former shrub planting, and a shallow treeline separates the grounds from the Thames. The grounds are distinctly more open in character than the western section around Orleans Gardens and Orleans Park School. Within the villa’s peripheries are smaller scale buildings which formed part of its estate, notably the restored Grotto, an 18th century icehouse, and a former stable block (both Grade II), that currently provides a café service and toilet facilities.

Fig. 17: The open grounds of Marble Hill serve a variety of community uses

Fig. 18: Original Gate House to Marble Hill

Fig. 19: Marble Hill House

Fig. 20: The original treeline is retained at the perimeters of the grounds, while sections to the front are being restored and improved

Fig. 21: The restored grotto

Fig. 22: 18th century icehouse

Fig. 23: Former stable block, currently serving as a café

The park is well-used by visitors and residents, accommodating a wide range of informal activities as well as sports, housing within the grounds a rugby field, a tennis court, and space to play cricket. The park, along with Orleans Gardens and the grounds of Orleans House, are both Metropolitan Open Land and Other Sites of Nature Importance. The southern side of the park feels fully separated from the surrounding suburban character and is a more peaceful space, though its character is slightly different, with remnants of the tree frame, in the process of being restored, which framed the house in views from the river.

At its south extreme, the gardens and park are separated from the river by a simple iron rail and the Thames path, the appearance of which is more urban than necessary with tarmac paving and a mixture of standard street furniture with some timber memorial benches, contrasting with the context of the house and its grounds. Beyond the path is the raised embankment which was altered in the 1920s to allow for more efficient use of the towpath. Here, one finds the access point to Hammerton's Ferry, which links the banks of Marble Hill to that of Ham House, and numerous moored boats, which add visual interest and a connection to the active river which carries through strongly into the adjacent riverside character area.

Fig. 24: The Thames path has simple paving and street furniture which could be more sympathetic to their context

Fig. 25: Hammerton's Ferry offers access to the river

The southwest section of the character area historically formed part of the grounds and gardens of a less grand house and has a slightly different character and feel, separate from the open character of Marble Hill Park. Orleans Gardens is located to the southwest of the area and the smaller open space has a more enclosed and intimate feel, being surrounded by a boundary of mature trees, the Thames Path to the South, and a low brick wall and Riverside to the north. The north side of Riverside has a taller brick wall which surrounds a dense and mature wooded area, the former grounds of Orleans House. This ‘wilder’ area has a distinct character to the surrounding open lands, with a sense of enclosure heightened by the robust boundary wall, and despite its relationship with Orleans House Gallery to the west, perhaps feels the most secluded.

Fig. 26: The low boundary wall of Orleans Gardens with mature planting around separating it from Marble Hill Park

Fig. 27: The ‘wild’ area to Orleans House feels more enclosed, an impression heightened by the tall brick wall

On the western edge of the character area are a group of historic buildings, including the remnants of Orleans House (Grade I) and Riverside House (Grade II). A private driveway branching from Riverside leads to three private residential houses, marked by an arched brick opening, giving an air of privacy and status. Central to the group are the remains of Orleans House which operates as a Gallery and sits within a slightly formalised garden. Completing the group is a former stable building, in use as the gallery café.

Fig. 28: The remnants of Orleans House

Fig. 29: Riverside House

Fig. 30: Entrance gates to the collection of buildings in the southwest corner of the character area

Fig. 31: Former stables, now in use as a café

Between this group and Richmond Road is a large sports ground and a group of school buildings. While the grounds fit into the open character of the area, the sprawling development of the schools is at odds with its setting and of contemporary design. Its appearance is somewhat mitigated, however, by mature planting and a robust brick wall to Richmond Road, as well as being set back into its grounds.

Fig. 32: View towards the schools from Richmond Road

Orleans Road, Montpelier Row, & Chapel Road

Orleans Road is a narrow street that intersects with Richmond Road, the entrance of which is flanked by two notable buildings: The Crown (Grade II), a two-storey high rendered late 18th century pub, the setting of which is interrupted by a large car park, and a timber framed exposed detached house of two storeys. These buildings give an indication of the scale and style of buildings beyond, which contrast with the Victorian cottages of Richmond Road, and the grander Georgian buildings to Montpelier Row.

Fig. 33: The Crown Public House and 1 Orleans Road

Fig. 34: View looking south along Orleans Road showing the tightknit townscape at its north side

The road is distinguished by its colourful cottages and former works buildings, narrow pedestrian space, and quaint village appearance. There are a variety of building materials and styles, with brick, render, timber all common. The intimacy of this former mews is emphasised by the buildings which rise directly from the pavement, though there are occasional front gardens which are well landscaped, adding visual interest, contributing to the village character, and interrupting the building line to avoid feeling too enclosed. Generally, buildings within the northern section of the road are more tight knit, terraced or adjoining buildings, whereas buildings to the south are set in wider gardens, transitioning to the more open character of the parkland beyond.

In terms of fenestration, sash windows with exterior shutters are predominant, but there are also casement windows along the street.

Fig. 35: Buildings rise directly from the pavement enhancing the intimate, enclosed feeling of the street

Fig. 36: Some houses toward the middle have deep and well maintained front gardens

Fig. 37: Contemporary development carries the scale and character

Fig. 38: A larger house with simple detailing continues the building line

The ‘Old Chapel,’ formerly The Montpelier chapel school constructed in 1856, is a more picturesque building, juxtaposing with the cottage/mews buildings, having two storeys, brick-built Romanesque arched windows with a dressing brick, and abuts the end house (no.29) on the west side of the road. No. 10 is an old storage building with a gable roof that imitates the form and scale of the chapel, creating a harmony in appearance. South of the Old Chapel, the west side of the road has a consistent row of single storey garages which are of no particular interest, but which continue the consistent streetscape and intimate feeling. Despite the garages, there is much street parking which disrupts the character of the street. The presence of cars also contrasts with the typical use of the Road as a key route for pedestrians and cyclists that frequently use the route to access Marble Hill Park at its southern end.

Some buildings, such as former stables, have been converted into garage space, found in No. 2A, 2B and 19. Houses become increasingly spaced toward the south end, where there is a transition between the residential area and the grounds of Orleans House and Marble Hill. Here, the houses are slightly larger and more similar in form, with long hipped roofs projecting into gardens, leaving wider spaces between that are concealed behind tall brick walls. These include No. 36 Orleans Road, the former coach house to the Grade II* Listed Montpelier House, and Park Cottage, which has robust gates and piers across from a public entrance to Marble Hill Park.

Fig. 39: The Old Chapel

Fig. 40: No. 10, a former works/garage building

Fig. 41: Single storey garage line the southwest side of the road

Fig. 42: Converted garage/works building

Fig. 43: No. 36 once served as the coach house to the Grade II* Montpelier House

Fig. 44: Park Cottage has robust gates across from the entrance to Marble Hill Park

To the east, the appearance of the area completely transitions to the formality and scale of Montpelier Row. Most of the properties within Montpelier Row are listed either grade II or II*, denoting its rich architectural value, primarily comprised of 18th century 3 and 4 storey terraced houses in gault or brown brickwork with red dressings, brick cornices and panelled parapets, although a small number are now rendered. The three groups of terraces are broken by Chapel Road, a short alley connecting Montpelier with Orleans Road. The east side of Montpelier is well planted, given a sense of privacy and exclusivity, though this soft green edge has been somewhat eroded by the insertion of parking bays. There are a single pair of 18th century cottages and a Victorian cottage, but otherwise the east side remains undeveloped. The road terminates at the impressive gates of the 18th century Southend House.

Fig. 45: The grand Georgian Houses to Montpelier Row

Fig. 46: A few of the houses have been rendered which disrupts their terrace

Fig. 47: The terraces have deep gardens and entrance porticos

Fig. 48: The east side of Montpelier Row is largely undeveloped but many car parking spaces have been inserted

Fig. 49: Pair of 18th century cottages

Fig. 50: The Row terminates at Southend House and its prominent gates

Connecting Orleans Road with Montpelier is the short and narrow Chapel Road, which presents two groups of two storey properties. The late 19th and mid-20th century buildings were built on the grounds of a former chapel, and are more balanced and reserved in their design, with balanced elevations in simple brick with little detailing – a transition from the varied character of Orleans Road to the formality of Montpelier.

Richmond Road

The Conservation Area extends north of Montpelier Row to encompass part of Richmond Road, which is predominantly residential. Buildings are typically two storeys and semi-detached, and while the majority are Victorian cottages there are examples of earlier and more contemporary development. A parade of three storey red brick Edwardian shops forms the corner of Crown Road, which appears prominent and as a visual focus to the mini roundabout. The upper elevations are restrained but the roofline is more dramatic with large gabled dormer windows punctuating the mansard roof. At street level the shopfronts are relatively attractive and provide colour and activity with forecourt space sometimes utilised for displays.

The northwest side contains a distinctive group of six pairs of early 19th century cottages with deep front gardens, well planted, which forms a green buffer between house and road. The unaltered shallow pitched slate roofs and pretty, decorative timber porches contribute to the surviving rural character of this group. A slightly more robust pair of altered Georgian houses and a group of red brick maisonettes complete the building line, and while their style varies, the scale, materials, and setting all compliment the character of the streetscape.

Fig. 51: Chapel Road

Fig. 52: Later infill development to the corner of Richmond Road and Crown Road

Fig. 53: Attractive group of Edwardian shops on the opposite corner

Fig. 54: Victorian cottages with deep gardens along Richmond Road

Architecture

Montpelier Row is defined by its balanced elevations and formally arranged layout. Tall stacks and mono-pitched roofs are predominant in the roof line, and parapets give a strong horizontal emphasis. It has decorative classical porticos and bay and sash windows. A very uniform frontage illustrates doorcases with classical pilasters, a wealth of high-quality architectural detail and embellishment provided by an array of decorative fanlights as well as iron railings and overthrows forming well-defined front boundaries enclosing front courtyards. Front gardens provide greenery with bushes and trees.

By contrast, Orleans Road is a rich patchwork of different styles and materials, all of which are sympathetic to the quaint mews character. A uniformity in scale helps retain a consistency in appearance, but a variety of materials, finishes, window treatments, and boundaries adds richness and visual interest. While brick is the most common material and timber sash windows the most utilised, there are exceptions of painted or rendered elevations, timber cladding, and leaded windows.

Richmond Road is simpler and more traditional, predominantly Victorian architecture. Here, houses are in balanced pairs, utilising gault brick with sash windows. Hipped roofs are unaltered and in slate with central stacks.

Fig. 55: Large gates are common to the taller Georgian houses of Montpelier Row

Fig. 56: Later terraces have projecting bays and lower boundaries to reflect their smaller scale

Fig. 57: The south side of Montpelier Row is more varied

Fig. 58: Typical cottages to Orleans Road

Fig. 59: The south side of Orleans Road becomes more open allowing for views to Montpelier Road beyond

Spatial Analysis

As predominantly an area of park land and gardens, the area is characterised by its openness, although there are discernible areas defined by the former grounds of Marble Hill House, or demarcated by natural or brick boundaries, such as at Orleans Gardens and Grounds, which have a more enclosed feeling.

The built environment is more varied – Orleans Road is a narrow and intimate setting, with houses built up straight from the pavement, but to a domestic two storey scale which avoids feeling overly enclosed. This is helped further by gaps in the streetscape due to occasional front gardens and the smaller scale of the garage group. Montpelier Row, with its taller and longer terraces is more commanding, although it is balanced with the east side remaining largely undeveloped. Gaps between the terraces are limited but important in breaking up the street from appearing as a single mass.

Richmond Road is more suburban, with good sized front gardens contributing to a verdant character and mitigating the impact of the busy road on houses. While the houses are quite closely spaced together, small gaps between and the setting into their gardens prevents a sense of terracing to Richmond Road.

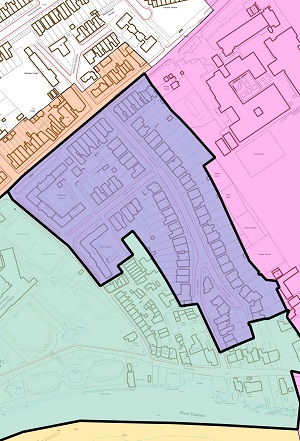

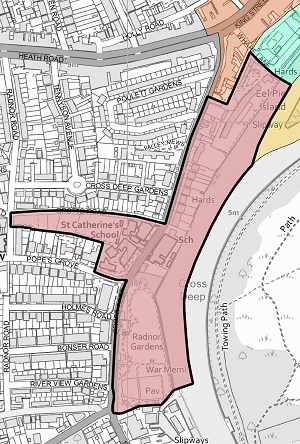

Character Area 2: Lebanon Park

Fig. 61: View north along Lebanon Park highlighting its suburban appearance

Summary Description

Lebanon Park is a very distinctive area of Edwardian houses built on the grounds and site of a large villa, Mount Lebanon, which burnt down in 1909. The grounds were set between the Richmond Road and Riverside on the gentle slope towards the river. This sub-area is unusually well defined, with the form and layout of the housing development little altered since its inception. It is the only speculative group within the Conservation Area.

Its special character is formed by the repetition of ornate features, the use of red brick and well-defined front gardens. The largely unaltered slate roofs form a strong rhythm in the street scene as the road runs downhill towards the river. Mature trees make an important contribution to the greening of the streets and add to the sense of enclosure.

Lebanon Court and Sion Court

Lebanon Court and Sion Court are purpose built 1920s developments of mansion flats which flank the Lebanon Park and Commercial Centre character areas. Given its residential purpose, it will form a sub-area of the Lebanon Park character area for the purposes of this appraisal. The blocks form a fortress like estate, occupying the corner of London Road and half of Sion Road, greater in height, scale, and massing than nearby developments, and blocking views towards other nearby development. Both blocks are four storeys of red brick walls with little modulation to a large, tiled mansard roof with robust stacks. Windows have been replaced with unsympathetic uPVC with overly reflective panes but retain their historic form and glazing bar patterns. Entrances are identical, with large timber double doors framed by a broken pediment. The appearance of the bulk is somewhat mitigated at street level by their setback from the road and manicured hedges above a low brick wall, but there is otherwise a lack of landscaping.

Fig. 62: Lebanon and Sion Courts are robust estates which dominate the western side of the character area

Townscape

Character

The entrance into Lebanon Park from Richmond Road is marked by tall 3 storey terraces on either side. The western block contains a parade of well-proportioned shops with flats above. The original shopfronts were of high quality with some unusual details, many of which survive. The upper storeys are of a simple design with good surviving original sash windows with their subdivision unaltered. The slate roof is supported at eaves level by white stucco brackets above a plain cornice. This architectural device links these outer buildings visually to the rest of Lebanon Park where it is used throughout.

Fig. 63: An attractive group of shops with good quality shopfronts on Richmond Road have architectural elements that tie them to the houses of Lebanon Park

Lebanon Park is lined with street trees giving the sense of an avenue, and there is a marked contrast to the noise and traffic of Richmond Road, instead experienced as a peaceful and tranquil suburban neighbourhood. The road gently slopes down towards the river, invisible beyond.

Houses are generally designed as pairs, set back from the pavement behind small front gardens, though there are some detached houses to corners, and short terraces to the western offshoot. Though there are variations in the design, they are highly complementary, using consistent materials and patterns, and most importantly, scale. Alterations are highly uncommon, with the most obvious being the loss of some stained-glass windows which erodes that characteristic richness of detail of the dwellings. Otherwise, the group is remarkably intact, and the erosion of this cohesiveness in any capacity would be viewed unfavourably.

Fig. 64: A typical short terrace

There are no sequential views, instead a straight vista towards the walls of York House Gardens and not such a sense of enclosure. At its southern extreme, the road forks, with an individual more idiosyncratic single house forming the apex of the resulting peninsula – the east half leading to a cul-de-sac, and the west to the embankment, including a single pair of houses, heavily modified, which match the group at the corner of Riverside.

Fig. 65: Standard speculative pair at the south end of Lebanon Park

Spatial Analysis

The area is predominately comprised of a linear road, with the emphasis of a boulevard heightened by street trees and the vertical emphasis from the architectural details of the houses. Pavements are wide and front gardens are of a good size, however, so that the sense of enclosure provided by the consistent streetscape gives the impression of a residential enclave rather than a tight urban space. Gaps between pairs contribute to this experience, offering views through to gardens and sky beyond.

Fig. 66: Gaps between houses allow for views through to rear gardens

Fig. 67: Gaps and hipped roofs help avoid the street feeling too enclosed and views through gardens contribute to the suburban character

Architecture

The architecture is dramatic with vibrant orange/red brickwork enlivened by embellishments such as terracotta panels, white stucco, and ornate white painted timber barge boards and porches. The white contrasts vividly with the rich tone of the brick. Gables topped with timber finials and contrasting decorative ridge tiles create a strong rhythm in the slate roofscape, the slope of the road accentuating the effect. The eye is drawn along the road by horizontal bands of white stucco.

Fig. 68: The houses share a consistent and largely unaltered sequence of patterns, forms, and materials

Window & Doors

Windows are timber casement generally pairs of two panes with a fanlight above, with the pairs separated by a central column. The fanlights within the ground floors of the projecting bays are typically stained glass, with only a few examples removed. One typology has a sash window adjacent to the entrance under the porch, which is also typically stained glass.

Windows to front doors and their sidelights also contain ornate stained glass adding architectural richness of the buildings, and the elevational fanlights usually match this design. Door styles are consistent, and most are original.

Roof types and material

Roofs are hipped with projecting front gables and finished in natural slate and are largely unaltered. Where concrete tiles have been used for patchwork repair, it is obvious and contrasting. Decorative ridge tiles are an attractive feature which add visual interest and elevate the appearance of the houses. Chimney stacks and slightly raised party walls add variation and richness to the roofscape and remain in situ, creating balance between pairs. Alterations are uncommon, limited on front and side elevations to rooflights. Many houses have rear dormer extensions, frequently a single dormer but sometimes a pair. These are limited to a single small window in width and generally placed toward the centre of the house so that they are largely invisible from the public realm. This scale and placement, and overall lack of intervention, has maintained an attractive and historic roofscape which makes a substantial contribution to the character and appearance of the Area.

Fig. 69: The roofscape remains largely unaltered apart from roof lights to some front elevations

Fig. 70: Artificial slate has a different appearance to the original roof finish

Porches

Porches add visual interest and a sense of elegance to the area with the decorative bargeboard, pillars, and rails. While the pattern of the bargeboards varies, rails are typically straight vertically or follow a rectangular geometric pattern. In contrast to the main roof, porch roofs are covered in terracotta tiles. Entrances are set in from the front elevation creating a smaller, internal porch, the flanks of which are adorned with decorative wall tiles

Fig. 71: Decorative tiles flanked the entrances with inset porches

Fig. 72: Timber porches generally follow two styles, such as this geometric pattern

Boundaries & Entrances

Fig. 73: Original timber boundaries

Front boundaries were traditionally of timber construction with decorative ball finials. Today, boundary treatments are more diverse, generally well-defined low brick walls and timber fences with low gates onto front paths. Where brick is employed, it is generally contrasting stock brick with some red detailing, often with simple iron rails and spear finials. Boundaries are consistently low and transparent, so that front gardens are easily observed, creating a sense of openness and contributing to a suburban garden character.

Fig. 74: Modern boundaries are a mixture of timber and brick, but are low and allow for views into gardens

Fig. 75: Attractive mirrored entrance with original door and tiled footpaths below a shared porch

Many of the decorative ceramic tiled paths survive ranging from simple black and white designs to more complex polychromatic patterns.

Gardens & Trees

Gardens are typically well planted with a variety of plant types which offers greenery in all seasons and contribute positively to the suburban character of the area, particularly as low boundary walls allow for longer views across multiple gardens. Some gardens have been overly landscaped with decorative hardstanding and plants in pots, which introduces a sense of formality which is at odds with the general character of the area.

Sometimes hedges are used for privacy, but again this feels too formal and detracts from the open character of the area. Privacy screening should instead be achieved through a rich variety of types and heights of plants, which will change seasonally and still allow glimpsed views into gardens.

There are some places where gardens have been lost to parking which further diminishes the suburban appearance, often creating abrupt, visual gaps in the boundary treatment, and is highly uncharacteristic of the Area.

Occasionally trees are planted in gardens but generally height comes from street trees – typically common lime, with some Norway maple to the southern half of the area.

Fig. 76: Mature street trees contribute to a suburban appearance and break up the building line

Fig. 77: Hard standing to front gardens disrupts the garden character and has an overly urban appearance

Paving

Pavements are of concrete paving slabs edged with granite kerbs reinforcing the high quality urban residential character.

Fig. 78: The area is paved in good quality pavers with granite kerbs

Street Furniture

The area is largely vacant of street furniture, though there is an excess of parking signs throughout. Lampposts are unremarkable, and of a standard modern design which is common throughout the Conservation Area: a green pole topped with a flat grey lamp.

Character Area 3: Historic Centre and Riverside

Fig. 80: View toward Eel Pie Island

Fig. 81: View down Church Street

Summary Description

At the centre of the Conservation Area are the remnants of the former village which evolved into a prosperous 19th century town. Given the heavy traffic along the A-roads and the prominence of the commercial area along King Street, the village’s prominence has been somewhat eroded, however, in contrast, the smaller routes which escape to quieter roads and to the river are more appreciated and form a haven for pedestrians. Church Street is the most attractive with its road and buildings retaining an intimate scale, with varied materials and good quality 19th century shopfronts. This intimate scale and character create welcoming surroundings which attract specialist shops and the liveliness of cafés and restaurants, many with al fresco dining. This village core forms a focal point when viewed from the Thames and is closely linked to it, a relationship emphasised by its pedestrianisation.

The Embankment to the centre of the Area served as a busy wharf until the end of the 19th century, but today forms its main public realm, with a landscaped promenade offering exceptional views to the river and Eel Pie Island, with places to sit, gardens to enjoy, and the occasional fishing. Narrow lanes connect the riverside to the commercial streets of the town centre. From the Embankment eastwards, large villas and houses were constructed along the river edge culminating in the extensive grounds of Marble Hill House. A lane, Riverside, connecting the Embankment to Orleans Road separated the houses from their river edge, leaving a narrow wedge of riverside garden remote from the houses. The Riverside Area demonstrates Twickenham's enduring history of river-related activity, both recreational and industrial.

Some of the larger houses have been demolished and their land subdivided and redeveloped as housing, but the essential form of the area survives unchanged. Environmental quality is high with much of the historic fabric surviving intact, notably, 18th century buildings, narrow lanes and footpaths bounded by high brick walls, all interspersed with mature trees which create an important backdrop to the built form. Riverside is an important route, channelling traffic between the Embankment and Marble Hill, making the transition from a vibrant urban character to a more peaceful rural one.

Character Appraisal

Townscape

Church Street has a gradual curve allowing hints of views towards the river along Water Lane and Bell Lane, which encourages exploration. There is a notable variation in design, materials, and roofscape and the often excellent 19th century shopfronts are interspersed from time to time with gates and alleys leading to back yards and outbuildings. The street makes a satisfying transition from the bustle of King Street to the calm oasis of the church and the adjoining square. The street and adjoining lanes are lined with 2 and 3 storey buildings, where the upper/attic storey is typically recessed with dormers, and this is evident on both historic and contemporary additions. Many of the buildings are listed and date from at least the 18th century, although burgage plots have survived since their medieval foundation. While Church Street is predominately commercial, Water and Bell Lanes are residential, lined with short terraces of workers’ style cottages with shallow front gardens. There is some infill development, which has respected this scale and the traditional building materials.

Fig. 82: Church Street attracts many pedestrians with its independent shops and restaurants, many with outdoor seating and displays which creates active frontages

Fig. 83: Wares displayed in front of shops add character

Fig. 84: Public House with outdoor seating

Fig. 85: 13 & 14 Church Street, two of the Grade II listed buildings along the street

Fig. 86: Residential Lanes branch off toward the river

Fig. 87: There is some infill development which is sympathetic to the scale and character of the historic village centre

The narrow lanes of the village which lead south offer the first glimpse of the river. The Embankment is a unique place, well landscaped and with sweeping views of the Thames, though it is separated by public car parking which somewhat disrupts the views and breaks the quaint village character. Cars travelling through and parking can make it difficult for pedestrians to cross, but at the water’s edge, there is a more definite sense of separation. Here, the surfacing is varied with many textures and materials such as brick, stone, gravel, and setts, but in a very formalised and planned manner.

Fig. 88: The embankment separated by car parking

Fig. 89: The embankment is pedestrianised and has a rich variety of landscaping details

Pin Oak trees line the bank separating the wide promenade from the road and parking as well as other soft landscaping. The promenade is lined with seating and offers a large stretch of public river access. At the west end, the car parking and the abrupt end to the Embankment deprive it of potential interest, and concealing a listed boathouse and deep-water dock beyond, within the grounds of Thames Eyot. The Diamond Jubilee Gardens to the north offer public open space and an interesting vantage point, but the space overall feels underwhelming and underused, and features such as artificial grass detract from its appearance. The electric substation stands out as a low point, but its appearance is somewhat softened by the small adjacent park. Heading east there is a grassed area at the base of Water Lane which is somewhat at odds with the rest of the area, but regardless, is well used and contributes to the openness and green space.

Fig. 91: The café within the Gardens

Fig. 92: Green space at the base of Water Lane

The tidal nature of the river, and the buildings and equipment associated with the working boatyards of Eel Pie Island make an enormous contribution to the interest and character of the Embankment. The view upstream is of great importance as direct contrast to the Embankment itself, the Thames curves into the distance lined by a thickly vegetated, apparently rural landscape.

Narrow lanes run downhill from the town centre to the quayside. The footpath between the close-knit houses provides the best way of appreciating the charm and small-scale detail of the historic village core. It curves gently around the backs of the historic riverside inn, the Barmy Arms, and the Mary Wallace Theatre. The path eventually emerges halfway up Church Lane giving an attractive view of the Grade II* church and graveyard.

Fig. 93: Narrow alley with view of the church

East of Bell Lane are a group of more robust buildings dating from as early as the 17th century, most listed, which illustrate the origins of the village as a summer escape for wealthy Londoners, their grandeur heightened by their riverfront setting. At the corner of Bell Lane, the buildings have mature front gardens, but to the east is another car park, which erodes their historic setting.

Fig. 94: This listed group illustrate the status of the embankment

At the base of Church Lane, one can either continue along the promenade via York House Gardens or continue along Riverside. Riverside is a narrow lane, with no pavements for most of its length. Much of it is enclosed by high 18th century walls creating a tunnel effect with restricted views. Vegetation clings to the tops of the brick walls with the canopies of mature trees visible behind enhancing a strong sense of enclosure, but also giving hints at the gardens beyond.

Fig. 95: Riverside has high walls on either side and feels enclosed

Riverside carries into Orleans Gardens and Marble Hill, with a distinct shift in character from the river side to parkland. Although Riverside House forms part of the Marble Hill character area, its peeking over the tall boundary wall marks an obvious point at which riverside development begins and thus marks the boundary of this character area. Heading west, the lane widens slightly and is punctuated by a contemporary building in a style inspired by boathouses to the south, as well as the Twickenham Yacht club, the drive of which was a former slipway and has good surviving setts and brickwork. To the north side is a small group of whitewashed 20th century houses set above the level of Riverside. The houses are of a standard speculative design and heavily modified, with one house in the group turning the corner to Lebanon Park. A mixture of boundary types along this stretch of Riverside is visually distracting and therefore to the detriment of its character.

Fig. 96: Riverside House

Fig. 97: Riverside heading east, the entrance to Marble Hill branches off at the end

Fig. 98: Rowing club with historic slipway materials forming its drive

Fig. 99: Much altered speculative housing group

The river is first revealed by a narrow glimpse along the former slipway which once served the Twickenham Ferry. The remaining sense of enclosure vanishes soon after with the appearance of the wide gravelly beach and slipway belonging to the White Swan public house which is frequently used for the launching of boats and offers clear views to the undeveloped northern side of Eel Pie Island, enhancing the secluded riverside character.

Fig. 100: Slipway to the Thames which once had a ferry service

Fig. 101: Slipway with gravelly beach and the north end of Eel Pie Island

Views towards this area are dominated by the substantial 2 storey canted bay window of Ferry House. This building forms one end of an excellent group of unusual, whitewashed 18th century houses, all listed. While Ferryside has a simpler balanced elevation and deep front garden, the rest of the group share the same slightly frivolous Regency seaside character. In front of the group, the pavement rises substantially from the level of the road, forming part of the formal tide defence in the area, and this, combined with the raised floor levels and wall and gate details, ensures that the houses do not flood at high tide.

Fig. 102: Ferry House

Fig. 103: Ferryside

Fig. 104: Part of the group of whitewashed listed buildings

Fig. 105: Sion House is Grade II*

The terrace of unique riverside houses wraps neatly around the corner of Sion Road to become an elegant red brick terrace of early 18th century town houses, including Sion House, and both the house and group are Grade II* Listed. The eye is drawn up hill by the strong horizontal emphasis of the elevations, and the unusually decorated overhanging eaves bolster this appeal. Opposite, the high walls of York House Gardens tower over the narrow road. The sense of enclosure in this southern section of Sion Road is strengthened by the proximity of the house fronts to the pavement. Tiny forecourts are strongly defined by simple iron railings and gates, but still, a good amount of planting is achieved, giving the terrace a distinct country flavour.

Fig. 106: Grade II* terrace of Sion Road

Fig. 107: No. 12 shows vertical emphasis, balance composition, and detailed eaves at top

Although a good distance from the river, the houses at the junction of Sion Road and Ferry Road share a common character with many of the riverfront houses although at a much smaller scale, reflective of the working class of people who would have lived and worked along the quay. The buildings decrease to modest 2 storey Victorian cottages and single storey outbuildings. The road is very narrow, and although picturesque, it has a distinct functional character in contrast to its surrounds. There are two charming terrace groups, the north (Sion Cottages, 1852) painted in pastel colours, and the east (Redknaps Cottages, built 1854), closing the view along Ferry Road as the road bends sharply through ninety degrees. Apart from the painting and a single roof light, the cottages remain largely unaltered and form an attractive and rare example of this scale of domestic dwelling surviving in the Conservation Area. The outbuildings are simple, with attractive bracketed eaves and tile roofs.

Fig. 108: A pair of simpler cottages at the corner with Ferry Road

Fig. 109: Sion Cottages

Fig. 110: Redknaps Cottages

Fig. 111: Simple but charming outbuildings to Ferry Road

Fig. 112: Riverside with the walls of York House Gardens rising above

The section of Riverside west of the junction with Sion Road returns to its former enclosed tunnel-like character, this time flanked by the walls of York House Gardens, until it emerges at Champions Wharf, just past Dial House. The house is 18th century and was formerly owned by members of the Twining family, later becoming a vicarage, with its notable sundial on its central pediment. Above the walls of Riverside, trees and vegetation can be seen from the road and provide another clue to the existence of the gardens. Views along the road are focused on the bridge which passes overhead linking the gardens.

The gardens are accessed via Champions Wharf, a quaint hard landscaped garden which has a sandy children’s play area and a large semi-circular seating area focused on a contemporary sculpture celebrating Alexander Pope. From there, there are excellent views over the stone balustrading of the promenade, across the Thames, to the working boatyards and slipways of Eel Pie Island.

Fig. 113: The bridge connecting the two sections of York House Gardens is a focal point

Fig. 114: Dial House

Fig. 115: Champions Wharf is a contemporary public space

Fig. 116: Views toward the river and Eel Pie Island from Champion’s Wharf

At the southeast corner of the parkette, an opening through the brick wall leads to a shady riverside path which contrasts with the adjacent hidden formal Italian style garden, part of the Grade II listed York House Garden. The western section is dominated by the dramatic group of statuary forming a 3-tiered garden fountain in a lily-pond. The southern garden is divided roughly into three sections, with two long octagonal gardens flanking a central circular element with pond at centre, the half being a rose garden. The gardens are surrounded by well-manicured hedges. Further exploration of the gardens involves crossing the stone balustraded bridge across which the sunken gardens of York House are found, behind the magnificent Grade II* York House itself.

Fig. 117: The Thames Path from within York House Gardens

Fig. 118: The Italian fountain

Fig. 119: Part of the south gardens

Fig. 120: The central element of the south gardens with small fishpond at centre

Fig. 121: The eastern ‘rose garden’

The sunken garden lies immediately to the south-east of the House and was constructed by Sir Ratan Tata circa 1906. It includes a rectangular, sunken area of lawn and grass banks with brick steps aligned on the central north-west/south-east axis leading to the two raised walks. Adjacent to the east corner of the sunken garden lies a Japanese Garden, bounded to the south by Riverside. The Garden, which was created by Sir Ratan in the early 20th century, contains an irregular pond spanned by a wooden bridge (late 20th century). To the east of this bridge stands an iron sculpture of Venus. The north-west end of the pond is surrounded by a rockery planted with a variety of plants including juniper and heather. The Japanese Garden is surrounded by woodland currently and to the northeast are two mid-20th century tennis courts which replaced the former kitchen garden.

York House stands in the north-west half of the gardens and is a large, three-storey H-plan house which dates originally from the mid-17th century but was remodelled in the early 18th century, with later alterations and extensions from the mid-19th (east wing) until the mid-20th centuries (the office wing to the west). The House is built of red brick with stone quoins and a cemented rusticated ground floor and a hipped roof.

North of York House, the grounds and setting of the house and garden have been much altered with its transition to municipal use. While a section of garden and walking path remains to the northeast, there is a large roundabout and car park to the northwest which has impacted its setting, somewhat softened through the use of soft landscaping and planted boundaries. The multiple extensions have also impacted its setting and are of little interest. Substantial gate piers supporting large decorative iron gates form the start of a formal yew lined vista to York House and are the best point from which to appreciate the grandeur of the original house.

Fig. 122: The sunken garden and rear elevation of York House

Fig. 123: The Japanese Garden with its wooden bridge

Paving

There is a variety of paving within the Riverside Character Area which is unique to the river frontage, particularly to the historic frontage with good surviving setts, as well as contemporary landscaping carried out as part of wider public realm improvements. Although richly varied, there is a consistent palette and various materials complimentary of each other.

Fig. 124: Large granite pavers indicate the high quality of landscaping throughout the area

Fig. 125: Historic sections of brick survive along Church Lane

Fig. 126: Later sections of brick survive along Church Lane toward the village centre

Fig. 127: Historic setts to the embankment at the end of Church Lane are indicative of previous landscaping treatments around the slipway

Fig. 127: The current promenade is more varied but still of a high quality

Fig. 128: Simple brick and setts are common landscaping treatments to the character area

Fig. 129: Detail of mixed materials to the former slipway at Twickenham Yacht Club

Fig. 130: Modern brick paving is utilised around the Civic Centre

Street Furniture

The character area is unique in that it primarily has a single lamppost style that does not appear elsewhere – simple yet elegant wrought iron post with vertical lanterns

Fig. 131: Style of lamppost unique to the riverfront Character Area

Character Area 4: Eel Pie Island

Fig. 133: The west side of the island with simple single storey bungalows

Summary Description

Eel Pie Island makes a vital contribution to the appearance and character of the Twickenham Riverside Conservation Area. The island is substantial, long enough to conceal the entire Twickenham quayside from Ham. The extreme ends of the island are thickly wooded and are designated as both Metropolitan Open Land, as well as an Other Site of Nature Importance (albeit, separately), providing valuable, quiet, and relatively undisturbed areas for wildlife. Consequently, when approached by up- or downstream, the island appears uninhabited. Views from the Twickenham and Ham banks reveal the opposite; the central section has been developed as an eclectic mix of housing and industry with trees interspersed. The northern section of the island is characterised by boat building yards and related activities on an informal layout. This is the closest part of the island to Twickenham and makes a significant contribution to the area’s character.

Character

Eel Pie Island has its own distinct character as an eclectic mixture of river-related industry and residential development. The island is accessed by foot at a single point, via a simple single span prestressed concrete bridge which was funded by the former Eel Pie Island Hotel. The bridge itself provides a unique viewpoint from which a series of views of Twickenham and the river can be gained, including most of the Conservation Area.

Fig. 134: The footbridge links the island to the mainland and offers unique views to the Area

Fig. 135: View south from the apex of the bridge

Fig. 136: View northwest with church visible at centre

At the foot of the bridge is a simple signpost with a map and community notice board, with the footpath breaking in opposite directions. The southern path is largely private and inaccessible to public visitors, occasionally closed off by a simple iron gate. The path is lined by tall fences and hedges, with a sense of enclosure further heightened by mature overhanging trees. Only occasional glimpses of buildings are possible, all of which are residential in nature, and there is a great sense of quiet and seclusion. At the start of the 20th century, the first houses on the island were built in this area: they were simple single storey timber framed bungalows and chalets generally clad in timber weatherboarding. Most of the plots are deep and narrow, intended to maximise the number with a riverside view, and this has resulted in a characteristic riverside elevation of gable ends. While many of the houses are not visible from the path, they can be viewed from the banks of the Thames and form an important part of the riverside character. Many of the original houses survive in this area, though typically with later alterations, and with examples of uncharacteristic brick cladding. (Reference to main pic)

Fig. 137: A footpath leads to the centre of the island and is flanked by plantings giving a rural character and sense of privacy