Hampton Village

Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation area no.12

St Mary's Church, Hampton

Contents

Part 1: Introduction

Outline of Purpose

The principal aims of Conservation Area Appraisals are to:

- describe the architectural and historic character and appearance of the area, which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications, and decision makers in assessing planning applications;

- raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area;

- identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as the negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

It is important to note that no Appraisal can be completely comprehensive, and the omission of a particular building, feature, or open space should not be taken to imply that it is of no interest.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication ‘Conservation Area Appraisal, Designation and Management: Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition)’.

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 (Sections 69 to 78).

Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to local conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan and national policy outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

Our overarching duty, as set out in the Act, is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

What is an Article 4 Direction?

An Article 4 Direction is made by the local planning authority. It restricts the scope of permitted development rights either in relation to a particular area or site, or a particular type of development anywhere in the authority's area. The Council has powers under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 to remove permitted development rights.

Article 4 Directions are used to remove national permitted development rights only in certain limited situations where it is necessary to protect local amenity or the wellbeing of an area. An Article 4 Direction does not prevent the development to which it applies, but instead requires that planning permission is first obtained from the Council for that development. View further information about Article 4 Directions to check if any permitted developments rights in relation to a particular area/site or type of development apply in your area.

Buildings of Townscape Merit

Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) are buildings, groups of buildings, or structures of historic or architectural interest, which are locally listed due to their considerable local importance. The policy, as outlined in the Council’s Local Plan, sets out a presumption against the demolition of BTMs unless structural evidence has been submitted by the applicant, and independently verified at the cost of the applicant. Locally specific guidance on design and character is set out in the Council’s Buildings of Townscape Merit Supplementary Planning Document (2015) which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Hampton Village Conservation Area was designated on the 14th January 1969. It has subsequently been extended three times:

- First Extension: 7th September 1982 (to include part of Station Road, the Waterworks, and part of the High Street)

- Second Extension: 29th January 1991 (to include part of Station Road, Upper Sunbury Road, Plevna Road, Avenue Road, Belgrade Road, Oldfield Road, Rose Hill, Beards Hill and Hampton Football Ground & Beveree Wildlife Site)

- Third Extension: 20th November 2023 (minor boundary rationalisations)

Following approval from the Environment, Sustainability, Culture and Sports Committee on 17th January 2023, a public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between 17th March and 28th April 2023.

This Appraisal was adopted on 20th November 2023

Other Planning Designations

The Thames Riverbank at Hampton, and Front Gardens to properties on Hampton Court Road are designated as Metropolitan Open Land (MOL).

Hampton Village Green, the grounds of Rosehill, and Beveree Playing Field are designated as Other Open Land of Townscape Importance (OOLTI).

Ormond Bank, Terrace Gardens, the Thames at Hampton, and Bell Hill are designated as Other Sites of Nature Importance (OSNI).

The Hampton Village Planning Guidance was adopted on the 13th June 2017. Its purpose is to establish a vision and planning policy aims for Hampton and assist in defining, maintaining and enhancing the character of Hampton. It can be viewed on the Council's website.

The Greater London Archaeology Advisory Service (GLAAS) completed its review of Richmond Borough's Archaeological Priority Areas in 2022. This identifies the Hampton Village Conservation Areas as being partly within the Tier 2 APA of Bushy Park and within the Tier 2 APA of Hampton. The full review can be found on the Historic England website as well as further information and guidance on Archaeological Priority Areas.

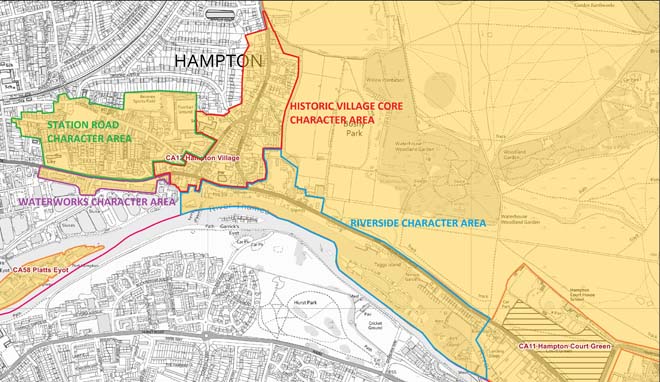

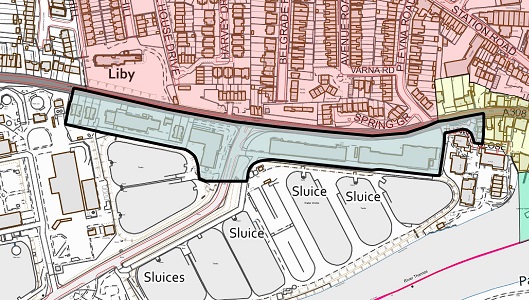

Map of Conservation Area

Summary of Special Interest

The Hampton Village Conservation Area covers the historic core of Hampton, as well as late 19th century development to the west, and the expansive mid-19th century Waterworks complex to the south-west. It contains buildings ranging in date from the 16th to the 21st centuries, with many of high architectural quality, including the Grade I Listed Garrick’s Villa, and Garrick’s Temple to Shakespeare. The village has a strong historic and visual relationship with the river which has shaped development along it, and allows for important views upstream and downstream which preserve this close relationship. The Waterworks are a substantial presence to the south-west, and their establishment in the mid-19th century had a considerable impact on the land west of the village and along the riverside. The village as a whole has gradually transitioned from a rural commercial settlement to a more suburban residential area, reflecting the urbanisation of the wider area in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

Historic Development

There is some archaeological evidence of prehistoric and Bronze Age activity in the Hampton area, but the settlement is thought to have developed during the Saxon period. The name ‘Hampton’ is Anglo-Saxon in origin, meaning “the settlement in the bend in the river” and is how the settlement is recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. Post-conquest, the manor of Hampton was given to Walter de St Valery, alongside the manor comprising Twickenham, Whitton, Isleworth, and Hounslow. It was held by the Valery family until 1217, when Thomas de St Valery was exiled, and it became property of Henry de St Albans, a London merchant. He in turn sold it to the Knights Hospitaller of St John of Jerusalem in 1273. The church would have formed the nucleus of this early settlement, with the historic core of the settlement formed around the triangular area of what is now the High Street, Church Street, and Thames Street.

The history of Hampton has always been closely associated with that of Hampton Court Palace. In 1494, Giles Daubeney, one of Henry VII’s most senior courtiers, leased Hampton Court from the Knights Hospitaller and started building the earliest parts of the Palace. Cardinal Wolsey acquired Hampton Court in 1514 and continued building the Palace. The Knights Hospitaller were supressed in 1540 and the manor became vested in the Crown. A new act of Parliament created the manor of Hampton Court.

Hampton remained as a small village to the west of Hampton Court Palace and Bushy Park, which had been created in 1491. In the mid-18th century, Hampton was formed of a group of buildings and gardens on either side of the High Street. The area surrounding the historic core is likely to have remained woodland and agricultural land until the 19th century.

Hampton grew in popularity from the late 16th century and into the 17th century, and it was in 1754 that David Garrick, the celebrated actor, bought the then Hampton House. Robert Adam worked on the house in 1756, and again in 1775. Garrick also developed the grounds, including building his Temple to Shakespeare, and commissioning Capability Brown, who provided landscaping advice, including on the construction of the tunnel beneath Hampton Court Road.

The Enclosure Act of 1811 led to the enclosure of old common land, and the widening of roads. The village had begun to grow from the early 19th century, and by the late 1820s, the parish church was judged to be too small. A new church was designed by Edward Lapidge, and paid for by the Church Building Commissioners. The foundation stone was laid on the 15th April 1830, and the new church was completed by the 2nd August 1831, and consecrated on the 1st September.

The most substantial change to the village came in the 1850s, with the construction of the Hampton Waterworks. The 1852 Metropolis Water Act required water companies to take water from above the tidal reach of the Thames. Waterworks were subsequently constructed along the Upper Sunbury Road. Large amounts of land were taken up with engine houses, reservoirs, and filter beds, and the development removed access to substantial sections of the riverside.

The railway arrived in Hampton in 1864. While it improved communication with London, the village did not see an immediate increase in population. The ‘New Street’ (now Station Road) was developed along the route of a historic trackway to link the station to the village.

Tom Tagg built the Island Hotel on Tagg’s Island in 1872 as demand for boats and leisure cruising was growing. In the early 20th century, the island and hotel were bought by Fred Karno, a former music hall impresario who built The Karsino hotel complex in 1913 and revived the island’s popularity. After Karno went bankrupt in 1925, the hotel entered a period of decline, until 1972 when it was demolished.

In the latter decades of the 19th century, market gardens were established to the north of the village core, and by 1900 there were 32 nurseries with 600 glasshouses. Many remained into the 1960s before the land was redeveloped for housing.

The Manor House estate was broken up in 1897, which released a large amount of land for development between the High Street and the railway line. This was the start of the wider development of the land around the historic core to the north and west.

The arrival of the tram in 1903 from Hampton Court to Hampton Hill resulted in the widening of Hampton Court Road, Church Street and part of the High Street. The wall in front of Garrick’s Villa had to be set back by 6 feet to accommodate the widening of the road for double tram tracks.

The 20th century saw further development around and in Hampton, with the loss of some of the large houses which had characterised the village, including Jessamine House (58 Thames Street) in 1956, Castle House in 1960 and St Albans in 1972. The development of the Manor House Estate, and the late 20th century infilling of a filter bed to create the village green and subsequent development, saw the changing character of Hampton from a rural village to suburb. Due to the proximity of Bushy Park and the River Thames, it retains some rural, green character on the eastern and southern side. The historic core is now predominantly residential, with the loss of small industry along the riverbank, and the retail core shifted to along Station Road.

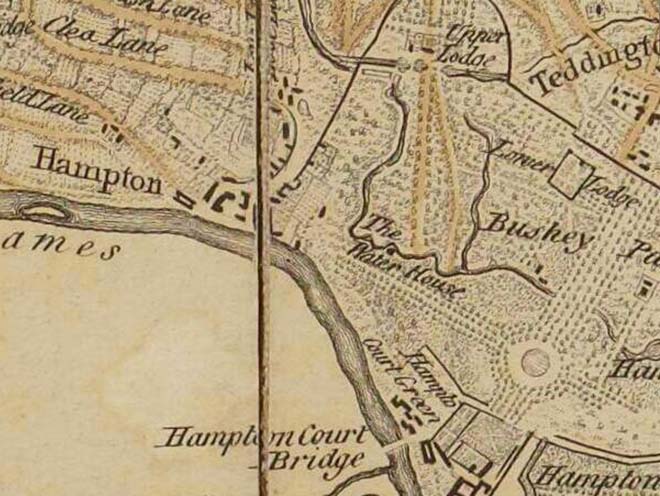

Figure 3: Extract from John Rocque's 'A Map of the county of Middlesex' (1757)

Figure 4: Extract from the 1869 Ordnance Survey Map of Middlesex

Figure 5: Extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey Map of London

Figure 6: Extract from the 1912 Ordnance Survey Map of London

Figure 7: Extract from the 1956 Ordnance Survey National Grid Map

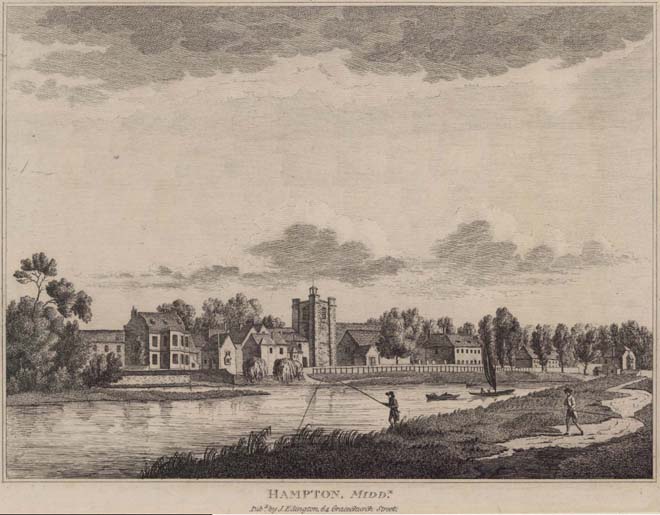

Figure 8: A view of Hampton from across the Thames in the early 19th century (1809)

Figure 9: A view of Garrick's Temple to Shakespeare from across the Thames (1839)

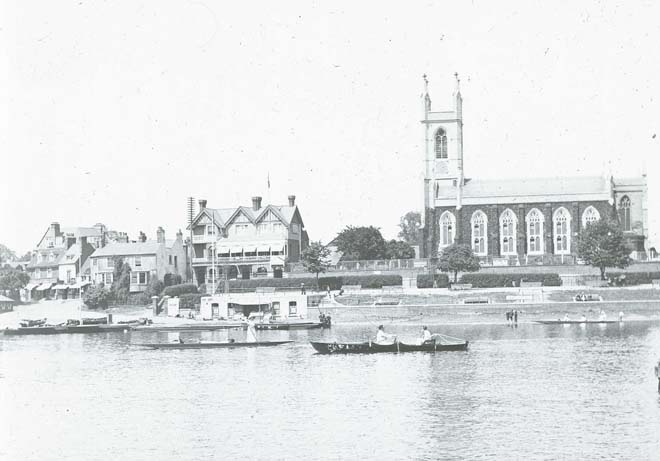

Figure 10: A view of St Mary's Church from across the Thames in the late 19th century, before the fire at The Bell public house in 1892

Figure 11: A view of St Mary's Church from across the Thames in the early 20th century

Figure 12: A view of the Waterworks looking west in the early 20th century

Figure 13: A view of Thames Street looking west in the late 19th century, before the fire at the Red Lion in 1908

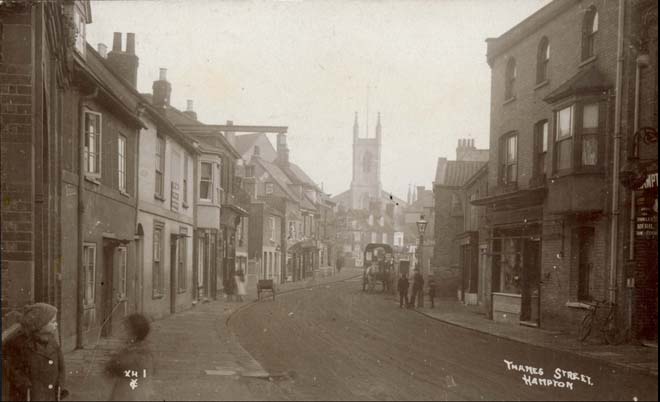

Figure 14: A view of Thames Street looking east towards St Mary's Church in the late 19th century

Figure 15: The former police station at 12 Station Road in the late 19th century, before it moved to no.68 Station Road in 1905

Figure 16: View from Tudor Road looking south towards the filter beds (where the Village Green is today) and Waterworks beyond in the early 20th century

Part 2: Conservation Area Appraisal

Location and Setting

This historic core of Hampton is centred around the junction of the road from Kingston to Sunbury (via Hampton Court) and the road north to Twickenham. It is bounded to the east by Bushy Park, the south by the River Thames, and the south-west by Hampton Waterworks. Hampton Court Green Conservation Area (no.11) and Bushy Park Conservation Area (no.61) adjoin the Conservation Area to the east and north respectively. Platt’s Eyot Conservation Area (no.58) is approximately 600m upstream.

Topography

The central historic core of the village is relatively flat with no discernible change in topography. Along Hampton Court Road the riverbank slopes gently down to the river, with the embankment becoming more pronounced towards the edge of the village at Garrick’s Lawn and Bell Hill Recreation Ground. St Mary’s Church is situated on a rise above the embankment, which results in the tower being highly visible across the Conservation Area. To the west, the land rises more steeply away from the river, with Rosehill overlooking the Waterworks, before levelling out to meet Station Road.

Townscape Overview

The townscape of the Hampton Village Conservation Area is defined along the major roads in a linear fashion, with many sequential views due to the gently curving nature of the roads. The historic core is comprised of buildings ranging from the 16th to 20th centuries, resulting in a variety of architectural styles. Larger 17th and 18th houses are often set back from the road behind high brick walls, contrasting with the smaller two-storey cottages which sit hard up against the pavement. Brown brick and stock brick are the most common materials, with the occasional red brick building usually later in date. White or pale coloured render is also common. Roofing material is inconsistent, with a mix of slate and clay tiles. There are few continuous runs of buildings in a similar style or material, emphasising the piecemeal development of the village as the streets were gradually built up. Most roads are fairly narrow, retaining their historic form, with close visual relationships between the houses on either side. Towards the northern end of the town, the townscape becomes more fragmented as expanses of greenery and long front boundary walls emerge.

The later 19th century and 20th century development around Station Road and Rosehill is more cohesive and planned, particularly the three roads of terraced housing running north-south from Station Road to the Upper Sunbury Road. Red brick is more prevalent in this area, alongside stock brick. Along Station Road, the historic townscape is more fragmented, with modern development separating the area from the historic village core, and dominating the townscape around the Green.

The Waterworks buildings are largely isolated from the rest of the village by the Upper Sunbury Road and are still a dominating, but positive presence in the townscape.

Throughout the Conservation Area there is wide variation in date and style of buildings, but with some consistency in materials. Buildings generally fall into the typologies of either large, detached houses, smaller terraced houses, or short terraces/parades of shops in similar style. Although the townscape is fragmented in places by new development, stretches of good quality townscape remain, with both high-quality architecture, and more modest dwellings.

Spatial Analysis Overview

Hampton has developed as a linear settlement along the major roads, with only later 19th century development infilling the gaps, most notably between Station Road and the Upper Sunbury Road. The larger houses generally sit in substantial plots set back from the road, although a few at the bottom of Church Street are hard up against the pavement. Smaller houses sit tight in their plots and hard up against the pavement. The streets are all fairly narrow, and many are now dominated by heavy traffic. To the north there is a more spacious quality, with the majority of houses set back from the road, and added greenery which creates a more rural, verdant character. Station Road is similarly more spacious, with wider pavements and buildings set back further from the road. The village green is the most prominent area of open space and a marked change compared to the densely developed historic core.

Character Areas

There are four sub-areas within the Conservation Area, each with a distinct character:

- Riverside

- Historic Village Core

- Station Road

- Waterworks

Figure 17: Map showing the character areas

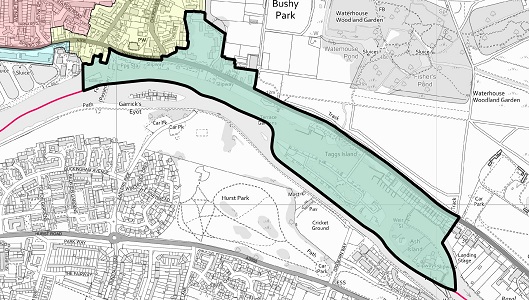

Character Area 1: Riverside

Summary

The Riverside Character Area extends from the eastern boundary of the Conservation Area at the edge of Hampton Court Green, along Hampton Court Road and into the historic village core, taking in Garrick’s Lawn and Bell Hill Recreation Ground. Past Bell Hill, the riverside, which was historically associated with the boatbuilding industry, has become privatised and fragmented, with little public access, which has created a barrier between the historic village core and the riverside. The Character Area also extends out into the River Thames, incorporating Ash Island and Tagg’s Island. Bushy Park Conservation Area (no.61) adjoins it to the north along Hampton Court Road.

Architecture and Townscape

The village of Hampton has always been closely associated with the river, with a ferry service to Hurst Park on the Surrey bank reputedly having existed since Domesday. The Riverside Character Area forms the entrance to the Conservation Area, and the approach to Hampton from the east, past Hampton Court Green. The boundary fence to Bushy Park on the northern side of the road allows for views into the Park and contributes to the verdant, rural character of the area. It also serves as a visual and spatial break from the grand historic buildings of Hampton Court and helps Hampton to retain its own character, despite the close historical connections between the village and the Palace.

Figure 18: The Bushy Park fence, showing views from Hampton Court Road into the Park

Along the southern side of the road is a short stretch of 1930s houses, with the occasional modern infill. They are two storeys, detached, many with steeply pitched half-hipped tiled roofs facing the road, in white render. Set back from the road behind brick walls, or fences, often with gates, they enforce a visual barrier between the road and the river. The spaces between the houses are a positive feature of the Conservation Area as they allow for glimpsed views of Ash Island to the south and maintain the more spacious semi-rural character of the area.

Figure 19: Houses on Hampton Court Road

At the end of the run of 1930s houses is the Grade II Listed ‘Swiss Chalet’, imported from Switzerland in the 1880s and assembled on the banks of the Thames. It is four storeys in all, with elaborate fretwork detail around each level, decorative bargeboards and a spirelet to the top. Only the upper storeys are visible as it sits behind a grey rubble wall topped with trellis and screened by trees, but it is still partly visible in views from the road due to its height and prominence in the street scene. This building also serves as a prominent visual ‘stop’ to the buildings along the south side of the road. Beyond the Chalet the river is suddenly visible to the left, with a grassy bank sloping gently down to the riverside, complementing the open green character of Bushy Park to the right. This tree-lined approach to Hampton emphasises the more rural nature of the area, and the fairly straight road allows for long, uninterrupted views east and west with few buildings.

Figure 20: The Swiss Chalet

Figure 21: The riverbank beyond the Swiss Chalet

Looking south across the river, the boathouses of Tagg’s Island become visible. This private island is accessed by a single arched footbridge from Hampton Court Road. In the late 19th century, Tagg’s Island was a highly popular leisure venue, a hotel having been established in the 1870s by the Tagg family of successful boat builders. Redeveloped by the former music hall impresario Fred Karno in the early 20th century, the leisure complex on the island was demolished in 1972. Today Tagg’s Island is characterised by boathouses moored around its edges, and there are long views of the river, with the tower of St Mary’s Church visible looking upstream.

Figure 22: View of Tagg's Island from the bridge

Figure 23: View looking west from Tagg's Island bridge with the tower of St Mary's Church visible in the distance

Beyond Tagg’s Island, the green, leafy approach towards Hampton continues. The first building which marks the beginning of Hampton is St Alban’s Lodge, the remnant of the lodge to St Alban’s Bank, a late 17th century house named after the fifth Duke of St Albans. It was demolished in 1972 after it had begun to collapse. The lodge is screened by a brick wall, which would have once been the boundary wall to St Albans, but which is now heavily rendered and in poor condition.

Figure 24: St Alban's Lodge

Figure 25: The riverbank between Tagg's Island Bridge and St Alban's Lodge

White Lodge is visible in oblique views through the Bushy Park fence on the approach to Hampton, but is largely obscured by greenery. This 18th century house with early 19th century white stucco front was historically the Park Superintendent’s Lodge and has a visual relationship with long views from the Diana Fountain in Bushy Park. Beyond White Lodge, behind a high brick wall, is the Bushy Park Stockyard, comprised of a collection of single storey stock brick agricultural buildings under tiled roofs.

Figure 26: White Lodge and boundary wall

Figure 27: Bushy Park Stockyard

On the other side of the road is the long, thin 18th century façade of Garrick’s House, named after the nephew of the famous actor who bought Hampton House, now Garrick’s Villa. Brick walls either side of Garrick’s House prevent views of the river and create a more enclosed character in contrast to the spacious, open character of Hampton Court Road. The tower of St Mary’s Church is visible in the distance.

On the left, Garrick’s Temple to Shakespeare emerges from the tree line, in an elevated position above the riverbank. Views of the river, and views across to the Molesey bank also emerge, contributing to the highly picturesque setting of the Temple.

Garrick’s Temple to Shakespeare is set within Garrick’s Lawn, a strip of the riverbank between the road and the river. Built in 1756 in dedication to Shakespeare, Garrick used it to house his collection of Shakesperean relics, alongside the statue of Shakespeare he commissioned from the Huguenot sculptor Louis Francois Roubilliac. It was built in the Classical style popularised by Palladio, to an octagonal plan topped by a dome, and an Ionic portico flanking the entrance. The Temple is Grade I Listed.

Figure 28: Garrick's Temple to Shakespeare

Garrick’s Villa lies on the opposite side of the road behind a stock brick wall with red brick dog-tooth detailing. Its elevated position results in a commanding presence looking out across the river, which is partly screened by greenery. Hampton House, as Garrick’s Villa was originally known, is thought to have medieval origins, having been merged into a single property from an amalgamation, and possibly extension of several timber framed cottages on the site. In 1754, the celebrated 18th century actor David Garrick purchased the house and estate and set about improving it. The architect Robert Adam made considerable alterations and enhancements in two phases, the first consisting of internal remodelling and alterations to the front elevation (including possibly the first iteration of the portico) soon after Garrick bought the house, and the latter in 1774/5 when the existing front with central portico was added. The western wing was added in 1865. The arrival of the trams and the beginning of the 20th century resulted in the front garden wall being set back to where it is today. A devastating fire on the morning of Saturday 25th October 2005 resulted in the collapse of the roof and considerable damage to the upper floors. A comprehensive rebuilding and restoration project was completed in 2011. Its long, stock brick façade with white portico, columns and cornice is a striking presence along Hampton Court Road and is one of several surviving large historic houses set in spacious grounds, although it is by far the largest and most significant, which is reflected in its Grade I Listed status.

Figure 29: Garrick's Villa

Beyond Bell Hill Recreation Ground, the Character Area transitions to the surviving small industrial and commercial premises to the rear of houses along Thames Street. Benn’s Alley is one of the last surviving narrow alleyways which led down from Thames Street to the riverbank. This tight knit, jumbled pattern of development supporting a number of uses is still served by slipways and landing stages, but the long-standing historic links to the river have declined. Past Benn’s Alley there is a visual and physical separation between houses on Thames Street and the river as it disappears from view.

Figure 30: Benn's Alley

Views

The view from the elevated viewing point at Garrick’s Temple to Shakespeare has been identified as a view of local importance in the draft Local Views Supplementary Planning Document. Overlooking Garrick’s Lawn, the Temple, and the river, with views to the Molesey bank and Hurst Park, this wide prospect emphasises the scenic setting of the Temple and between Garrick’s Villa and the river.

Figure 31: View from the top of the Loggia on Garrick's Lawn

The view from Bell Hill Recreation Ground out across the river has been identified as a view of local importance in the draft ‘Local Views’ Supplementary Planning Document. Looking out across the river to the Molesey bank and Hurst Park, but also with views both upstream and downstream to Tagg’s Island, this view is a reminder of the close relationship between the village and the river.

Figure 32: View looking east (downstream) from Bell Hill Recreation Ground

Figure 33: View looking west (upstream) from Bell Hill Recreation Ground

Figure 34: View looking west along Hampton Court Road at the transition from Hampton Court Green towards Hampton Village

Figure 35: View looking west along Hampton Court Road towards Hampton Village, emphasising the verdant character of the area

Open Spaces

Garrick’s Lawn (a Grade II Registered Park and Garden) lies opposite Garrick’s Villa between the road and the river. The setting for Shakespeare’s Temple, the Lawn is widely believed to have been laid out on the advice of Capability Brown, whom Garrick consulted on how best to lay out the grounds of his Villa. Today the Lawn is a secluded area of green space, partly screened from the busy Hampton Court Road due to the difference in levels and is also demonstrative of the ‘broken-up’ nature of the riverbank, with access only from the road and not from along the riverbank.

Upstream from Garrick’s Temple is Bell Hill Recreation Ground. This is historically the place where boats and barges would have moored to load and unload, as it was one of the few areas on this stretch of the river where boats could be taken out of the water. It was first fenced off in 1863 to become ‘The Prince’s Gardens’ in celebration of the marriage of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) to Princess Alexandra. It decayed over the subsequent 20 years, until 1884, when the Rural Sanitary Authority redeveloped the area in the form it is today with the upper and middle levels. It is dominated by a large expanse of hardstanding, with some flowerbeds along the upper level, and is a somewhat underutilised space which is primarily used for the mooring of boats. Similarly to Garrick’s Lawn, it is isolated from longer river walks due to the fragmented nature of the river frontage. There are long views looking both downstream and upstream, and there is a good vantage point for the Church, which emphasises its elevated position.

Figure 36: Bell Hill Recreation Ground

Street Furniture

A notable feature on the southern side of the road is a surviving 18th or 19th century milestone giving the distances to Sunbury, Staines, Windsor, Hampton Court Bridge, and Kingston Bridge.

Figure 37: Milestone

A pair of surviving Victorian ‘stink pipes’, historically used to vent sewer gas, are situated along Hampton Court Road, one halfway along the stretch of 1930s houses, and the other opposite White Lodge.

Other street furniture is restricted to modern LED lampposts, standard London bus shelters/flags, and road signs.

Figure 38: Stink pipe at the eastern end of Hampton Court Road

Figure 39: Stink pipe at the western end of Hampton Court Road

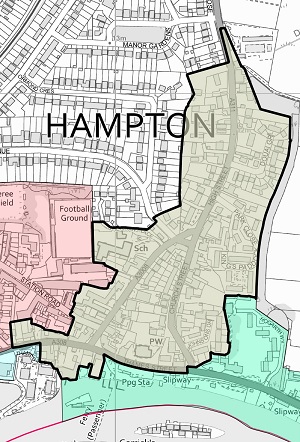

Character Area 2: Historic Village Core

Summary

The historic village core is centred around the triangular form of Church Street, Thames Street, and High Street, with the High Street extending northwards, and Thames Street extending westwards towards the Waterworks. It contains the major part of the early development of Hampton with buildings ranging in date from the 16th through to the 20th centuries. Originally the retail and commercial centre of the village, it has increasingly been given over to residential as shops and businesses moved out along Station Road. Today the village core is dominated by the busy roads north to Twickenham up Church Street and the High Street and west to Sunbury along Hampton Court Road, Thames Street and the Upper Sunbury Road. The areas of historic development have also become more fragmented and interspersed with more modern developments which have diluted the historic character of the area.

Architecture & Townscape

Thames Street

Thames Street acts as a division between the river and the village, with a brick wall and then iron railings forming a physical separation between the road and Bell Hill Recreation Ground. Views of the tower of the Church abound along its length, which is otherwise dominated by traffic heading out west towards Sunbury.

At the junction of Church Street and Thames Street is the oldest surviving building in Hampton: the former Feathers public house, now nos.2-6 Thames Street. Dating back to the 1540s, with a later frontage and rear extensions, it is a low two-storey building in white render, under a clay tile roof, with a pair of double-height canted bays to the central section. A public house until 1792, it was subsequently divided into tenements and a blacksmiths yard. It remains as three separate dwellings today and is Grade II Listed. It sits hard up against the pavement and is a prominent frontage at the beginning of Thames Street.

Figure 40: 2 - 6 Thames Street

Set further back from nos.2 – 6 and the road is the late Victorian former vicarage. Constructed in 1884, it is at least the third vicarage on the site. The view from Thames Street is of the rear of the building, a double fronted main section, with two prominent gables and a small central dormer, and a two-storey wing to the side set back from the main part of the building. The boundary wall is in a poor state of repair with areas of hard cement pointing leading to degrading bricks.

Figure 41: The former vicarage

St Mary’s Parish Church is one of the most prominent buildings in Hampton. The present church was built between 1830 (the foundation stone was laid on the 15th April 1830) and 1831 (completed on the 2nd August and consecrated on the 1st September). It was designed by Edward Lapidge who also designed Kingston Bridge, as well as St John’s in Hampton Wick and St Andrew’s in Ham, and who is buried in the churchyard. It is built in the Decorated/Perpendicular style in stock brick, under a slate roof, with a two-stage west tower with corner pinnacles. The chancel was added in 1888 by A.W. Blomfield. The Church is set back from the road in a small graveyard, and sits in a prominent, elevated position overlooking the river. The tower is visible in long views from as far away as Hampton Court Bridge to the east, but also from the three approach roads into the historic village core, and in unexpected views between buildings.

Figure 42: St Mary's Church

The Bell Inn, 8 Thames Street, is a characterful late 19th century public house, rebuilt after a fire in 1892. It is three storeys, in brick and roughcast render, with a timbered galleried first floor and three half-timbered gables above. A prominent pediment above the right-hand door could be a surviving remnant of the original building.

Figure 43: The Bell Inn

The spacious character of the road, with the river on the southern side and the buildings largely set back from the road on the northern side develops into a narrower, more enclosed road towards the junction with High Street. Beyond The Bell is no.20 Thames Street, a Grade II Listed early 18th century double-fronted former shop in brown brick, with red brick detailing. This modest 18th century house is contrasted with the more substantial no.1 Thames Street opposite, in similar materials, with white string courses and a slate mansard roof behind a parapet. Alongside no.3 it forms a pair of substantial 18th century houses at the bottom of the High Street backing on to the river. This is the start of the subdivision of the riverbank into individual, privately accessed plots and consequently the close relationship of the historic village with the river is eroded.

Figure 44: 20 Thames Street

Figure 45: 1 Thames Street

Figure 46: 3 Thames Street

Beyond no.3, Thames Street narrows, with the buildings either side hard up against the pavement providing a near continuous frontage on either side. No.15 is of similar date to nos.1 and 3 but of smaller scale, reflecting the overall smaller scale of the rest of Thames Street. It is predominantly three storeys on the south side, and two on the north. The north side is more cohesive than the south, with only nos. 30 & 32 breaking the historic building line. Nos.22 – 26 are all 18th century Grade II Listed houses with former shopfronts and form a varied roofscape with differing heights and materials. Many buildings along Thames Street were formerly shops, as it was historically one of the main commercial and retail streets in Hampton, and have now been converted into residential, including the former Post Office at no.21. Opposite no.21 is no.36, with its unusual dark timber framed and panelled oriel window with Gothic style window insets at odds with the 18th and 19th century modest vernacular style of the street. The end of the northern side is prominently demarked by the red brick former fire station (no.42) built in 1897. It is two storeys in red brick, with red sandstone bands and topped with a pair of Dutch-style gables with ball finials, and segmented window and door overarches. The retained large ground floor red doors contribute to its character and prominence in the street scene. Beyond the former fire station, the northern side of the road opens up, with the pair of 18th century houses at nos.54 and 56 Thames Street set back from the road. No.60 (Canister House, built 1740) is set further back from the road and is screened from view by a wall and vegetation. The 18th and 19th domestic character of the historic village core is brought to an abrupt end by the substantial mid-19th century Gault brick Riverdale and Morelands Waterworks buildings on the southern side of Upper Sunbury Road.

Figure 47: 15 Thames Street

Figure 48: 22 Thames Street

Figure 49: North side of Thames Street

Figure 50: 42 Thames Street (former Fire Station)

Figure 51: 54 & 56 Thames Street

Church Street

Church Street is characterised by substantial 17th and 18th century houses, with some smaller 18th century cottages at the northern end. Historically a narrow road, Church Street was widened in the early 20th century with the arrival of the trams; many of the houses on the northern side sit hard up against the pavement, with only the run of 1930s properties on the western side set back from the road.

The curve in the road up from Thames Street results in any views of the river quickly being hidden. No.2 Church Street (The Old Grange) is the earliest house on the street, with mid-17th century origins. It is three storeys, in white render, with a pair of plain Dutch gables and its distinctive earlier architectural style is prominent in the streetscape. No.4 (Orme House) by comparison is a substantial 18th century brown brick house, with a white stuccoed ground floor with central doorcase with carved consoles and small central pediment at roof level. In contrast, opposite is the modest no. 9, contemporary in date with no. 4, but with added 19th century wings to the front. This is characteristic of the smaller, predominantly two-storey nature of the western side of the road, which was generally developed later than the eastern.

Figure 52: The Old Grange, 2 Church Street

Figure 53: Orme House, 4 Church Street

Figure 54: 9 Church Street

No.6 (Staple Grove) reflects no.4 (to which it is attached) in style, but is two storeys in stucco, and set back from the road. This materiality is continued in the pair of mid-19th century houses at nos.8 and 10 which are similarly set back from the road. They are prominent in the streetscape due to their colour and height. The continuing curve of the road results in sequential views looking south, with these prominent Listed houses only visible briefly.

Figure 55: Staple Grove, 6 Church Street

Figure 56: 8 & 10 Church Street

The curve of the road and breaks in the building line give rise to views of the church rising behind the two storey buildings on the western side of the road. The former Methodist Chapel (now no.17) is the most prominent building on the western side, with its steeply pitched roof and surviving window and door under polychromatic brick arches. It is somewhat isolated in the historic streetscape between 1930s development and is in contrast to the substantial two/three storey buildings on the other side of the street.

Figure 57: 17 Church Street (former Methodist Chapel)

On the eastern side, the substantial Listed buildings give way to modest two storey 18th and 19th century cottages. These are two storeys, with the majority either painted or rendered, under pantile or slate covered pitched roofs. No original windows remain, and some have been replaced with unsympathetic styles. They all sit hard up against the pavement, and the straightening out of the road allows for longer views north and south.

Figure 58: 28 - 40 Church Street

The road opens out at the top of Church Street to the small area of land known as ‘The Triangle’ at the junction with the High Street. On the southern side of the Triangle is a short mid-19th century terrace in stock brick which continues the modest, two-storey character of the northern end of the High Street. In contrast is the former White Hart public house, set back from the road in a large plot. Built in 1901 to replace an earlier structure, it is a substantial three-storey red brick building, under clay tiles, with a corner turret and hipped gable end to the front. Its distinctive style is prominent in the surrounding area, and it gives an additional sense of spaciousness to the area surrounding the Triangle.

Figure 59: Former White Hart public house

Figure 60: 62 - 68 High Street

High Street

The High Street is the longest road of the three comprising the historic village core and runs through the village from the junction with Thames Street and up out beyond the end of the historic village towards Hampton Hill. It is the most architecturally varied of the all the roads in the Conservation Area, with smaller 18th and 19th century former shops at the southern end giving way to substantial detached houses with some later infill development. The wider road also gives rise to a greater sense of space, which is enhanced by mature trees and greenery in many front gardens. The gentle curve of the road allows for sequential views of the varied architectural styles of houses, with the church tower often visible in the background when looking south.

A curved mid-19th century terrace of two storeys in white render under slate roofs is situated on the eastern side of the junction with Thames Street. Historically, all were shops, but today only the corbels and pilasters to no.2 survive, albeit heavily painted. It holds a visual relationship with no.1 High Street opposite, the former Red Lion public house. The current building was constructed in 1908 to replace the previous public house buildings which were partly destroyed by fire. Now converted into offices, the building occupies a prominent position on the junction of Thames Street and High Street. There is a good view of the Church tower in the gap between nos.6 and 8 High Street. 8, 8a and 10 are complex interlinked structures dating from the late 16th or early 17th century, with 18th century additions and no.10 refronted in the mid-19th century.

Figure 61: 2 - 6 High Street

Figure 62: The former Red Lion public house

Figure 63: 8 High Street with St Mary's Church tower behind

Figure 64: 10 High Street

Opposite is a former bank on the corner of High Street and Station Road, in Queen Anne revival style with a distinctive stone ground floor and prominent doorcase. Along Station Road at nos. 2 – 12 is a row of two storey mid-19th century houses. The first three are double fronted, with a central niche on the first floor and prominent window surrounds. No.12 is the old police station which was purpose built after approval from the Home Office in December 1846. It remained as Hampton police station until the construction of 68 Station Road in 1905.

Figure 65: 7 High Street

Figure 66: 2 - 6 Station Road

12 – 14 High Street is unlisted but of similar date to neighbouring buildings. It retains elements of a shopfront, including pilasters, decorative corbels, and fascia. Of similar scale is the Jolly Coopers public house, an early 18th century public house in brown brick with a tiled mansard roof behind a plain white parapet. Alongside nos.18 – 22, it forms a short run of well-preserved modest early 18th century buildings, in contrast to the grand 18th century houses on Thames Street and Church Street. No.22 has a pair of unusual curved timber doors to the corner entrance door, with an ornate wrought iron grille in the fanlight above.

Figure 67: 12 - 14 High Street

Figure 68: The Jolly Coopers public house and 18 - 22 High Street

Figure 69: 22 High Street with the church tower visible on the left

Modern development either side of the road enforces a visual and physical break between the surviving historic development along High Street. A highly prominent building is the telephone exchange (no. 34) a large 1930s mock-Georgian construction. At four storeys, with an array of masts and antennae on top, it is tall for the surroundings and is visible in views between buildings from Church Street.

Figure 70: 1930s houses on the east side of the High Street

Beyond, on the opposite side of the road are nos.33 and 35 High Street, a pair of Grade II Listed 1720s houses, in stucco with a tiled roof behind a parapet, with a simple cornice and window surrounds. They are well set back from the road behind a brick wall and front gardens. Next is nos.37 – 39, again a former shop, now converted to residential, in stock brick with red brick banding. The first-floor arched windows have high quality brick detailing, and the central window is flanked by a pair of thin stone columns. The front gardens of the 1930s houses on the opposite side of the road give a slightly more spacious character to this stretch of the High Street, as do the grounds of the Twickenham Prep School. The main house, historically known as ‘Beveree’ has early 19th century origins, but was much rebuilt after a fire in 1867. Set in substantial grounds, it is largely screened from the road by trees.

Figure 71: 33 & 35 High Street

Figure 72: 37 - 39 High Street

Figure 73: Twickenham Prep School (formerly Beveree)

As the High Street continues north past the Triangle, further grand 17th and 18th century houses abound. No.78 is a late 17th century house with a pair of Dutch gables either side of a later projecting brick bay to the front. The cupola to the top along with the bottle balustrade draws the eye upward, and the architectural contrast between the Dutch gables and brick bay results in the building being prominent in the street scene. The blue plaque on the façade commemorates Alan Turing, the code breaker who once lived there. Similarly prominent is no.84, a three-storey stock-brick house, part of a small group of three 18th century buildings between no.78 and Park Close. The church tower is once again visible to the south. The houses on the west side of the road are set back behind brick walls and screened by trees.

Figure 74: 78 High Street

Figure 75: 80 - 84 High Street

No.90 dates from the early 18th century, and is of two storeys, with a prominent first floor splayed bay above the doorway on thin columns. It is set back from the road and is partially obscured by a later brick outbuilding. Further up the road on the western side is no.67, dating from at least the first half of the 19th century, and likely a former farmhouse. It has a projecting wing to the front as it set forward of the building line later established by the surrounding 1930s development.

Figure 76: 90 High Street

Figure 77: 67 High Street

Grove House, 100 High Street is one of the most substantial and significant large historic houses in the village, which is reflected in its Grade II* Listing (the only Grade II* structure in the Conservation Area). Built c.1669, with enlargement in the 18th century, and remodelling in the 19th and 20th centuries, it is two storeys, in brown brick with red brick detailing, white quoins and string courses under a slate roof. The initial range of five bays is extended to the left by a further two bays. The front porch is crowned with a pair of eagles. The wall to the front dates from at least the 1920s, and the house is further screened by a line of silver birch trees.

Figure 78: Grove House, 100 High Street

Figure 79: View of 100 High Street behind wall and trees

Late 19th century and early 20th detached two storey houses continue along the west side of High Street, with little continuation of architectural style. No.87 is a Grade II Listed 18th century house which sits hard up against the pavement and forward of the building line along the western side of the High Street. The high brick wall opposite screens several houses from view, with the first floor of no.110 visible. No.101 is similarly behind a brick wall but set back and slightly elevated. Opposite is a short run of three mid-19th century cottages, all former shops, and then the former Dukes Head public house. Beyond the garage are three detached cottages (nos. 132-136) which mark the northern extremity of the conservation area where it abuts Bushy Park Conservation Area to the east.

Figure 80: 116 - 124 High Street

Figure 81: 132 - 136 High Street

Views

The view of St Mary’s Church from Hampton Court Road/Thames Street has been identified as a view of local importance in the draft Local Views Supplementary Planning Document. The church tower becomes visible in the background as one approaches the village from Hampton Court before the whole of the church is visible past the junction with Church Street. The tower is also visible from numerous locations around the village.

Figure 82: View of St Mary's Church tower from Hampton Court Road

Figure 83: View looking west along Thames Street from the junction with High Street

Figure 84: View looking east along Thames Street

Figure 85: View looking east along Thames Street

Figure 86: View of Church Street looking north

Open Spaces

The Triangle is the apex of the triangle of streets which form the historic village core and is situated at the junction of Church Street and High Street. It is a small area of hardstanding, bounded on two sides by the main roads, with a tree to each corner, a single bench curved around one of the trees, an information sign, and the remains of a sign which formerly advertised the White Hart public house. It is a somewhat forgotten small area of open space which is now dominated by the heavy traffic along Church Street and High Street.

Figure 87: The Triangle

Street Furniture

A cast-iron post and rail fence runs along the raised pavement by the church.

Elsewhere, street furniture is minimal and largely confined to LED lampposts and standard London bus shelters/flags. A few bollards are strategically placed to prevent vehicles mounting the curb. Further street signs largely utilise existing posts, and any additional freestanding ones are sparsely positioned.

Figure 88: Fenceposts to the Church on Thames Street

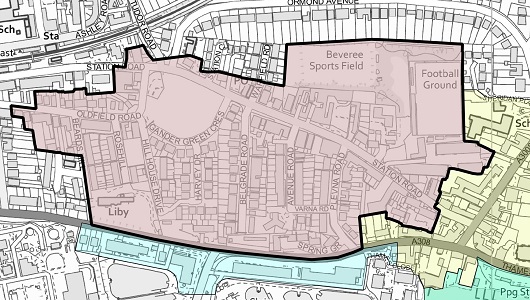

Character Area 3: Station Road

Summary

The Station Road Character Area is comprised of the predominantly 19th century development which arose after the arrival of the railway in 1864. Station Road follows the route of a historic laneway, marked on Rocque’s 1757 Map of Middlesex as ‘Old Field Lane’ before becoming ‘New Street’ with the arrival of the railway, and ‘Station Road’ by 1894.

Architecture & Townscape

Station Road

Station Road is separated from the historic village core by modern development on both sides of the road. No.30 is a mid/late 18th century double fronted house with prominent canted bay. Facing west up Station Road it is somewhat isolated amid 20th century development, alongside the short terrace at 33 – 41 Station Road. The historic streetscape is resumed at nos.51 – 61, a terrace of two storey mid/late 19th century houses, in various shades of pastel-coloured render, under slate roofs. The doors have simple moulded arched surrounds above a plain fanlight. All are slightly set back from the road with small front gardens behind white picket fences. A run of late 19th century and early 20th century buildings lead up to the junction with Plevna Road. This includes no.67, which retains elements of a surviving original shopfront including recessed doorway with deep fanlight above, clerestory lights with ventilation grilles, and a simple corbel.

Figure 89: 30 Station Road

Figure 90: 51 - 57 Station Road

Figure 91: 67 Station Road shopfront

Opposite are nos.40 & 42 and 44 Station Road, three 18th century cottages, the former in stock brick and the latter in black wavy edge weatherboarding, a material not common within the Conservation Area, but which nevertheless contributes to the more rural, village character of the area. The adjacent terrace at 46 – 54 Station Road are earlier 18th century and more prominent in the street scene. They are three storeys, with a continuous stock brick frontage and the roof hidden behind a parapet. Each house is two windows wide, with a simple moulded doorcase with pediment. They are well set back from the road, with all but one behind a low boundary wall with greenery. While architecturally modest, they are distinguished in the surrounding area as some of the earliest development on Station Road. Beyond is the continuation, on both sides of the road, of the later 19th century and 20th century short parades of shops. This central part of Station Road is tree-lined with wide pavements and is not dominated by traffic like the historic core.

Figure 92: 40 - 44 Station Road

Figure 93: 46 - 54 Station Road

Immediately noticeable in the street scene is nos.77 - 81, an early 20th century former cinema, in white roughcast render with pair of thick columns flanking a central entrance way. Opposite, and near contemporary in date, but contrasting architectural styles is the former police station (no.68). It is a substantial red brick building under a slate roof, with three tall chimneys and four dormers. There are two doors to the front, both with stone surrounds; the primary door retains the word ‘POLICE’ over the top. The lamppost at the front is contemporary with the building. The site is an allocated site in the Council’s adopted Local Plan. Nos.70 – 74 beyond are a short parade of shops and the most architecturally detailed. They are three storeys, with half-hipped timbered gables to the front with decorative bargeboards and decorative finials. The shopfronts vary in quality, with no.70 the best preserved with recessed entrance door with tiled floor, mullions with decorated spandrils, glazed brick pilasters, and large stone corbels. Nos.72 and 74 are modern shopfronts but retain the glazed pilasters and stone corbels. Nos.76 – 80 are three buildings with gable ends facing the street; no.80 has retained its recessed door, stall risers and cornice below the fascia, as well as simple corbels and glazed brick pilasters. Opposite, the southern side of Station Road is predominantly two-storey modest shops in either red brick or stock brick under slate roofs. Few original features remain, most noticeably corbels. Beyond no.101, Station Road reverts to residential with two pairs of mid-19th century houses and a modern infill development.

Figure 94: 77 - 81 Station Road (former cinema)

Figure 95: 68 Station Road (former police station)

Figure 96: 70 - 74 Station Road

Figure 97: North side of Station Road

Figure 98: South side of Station Road

Figure 99: 99 & 101 Station Road

The World’s End public house is a large 1930s building which replaced an earlier building on the site. It is two storeys under a large, hipped roof with a pair of tall chimneys; there are glazed tiles to the ground floor and a rendered first floor with a central brick section under an arched hood.

Figure 100: The World's End public house

Station Road opens out with the village green on the southern side, and buildings set back from the road in more spacious plots on the northern side. Nos.104 and 106 are a semi-detached pair of late 19th century houses, with full height canted bay windows with timbered gables, prominent chimneystacks, and gabled porches. They are prominent in the street scene and overlook the Green. Nos.110 and 112 are a pair of mid-19th century houses, in stock brick under a slate roof and are one of the earliest buildings in the surrounding area.

Figure 101: 104 & 106 Station Road

Figure 102: 110 & 112 Station Road

The Railway Bell public house is formed of part of a range of two storey brick cottages with 18th century origins. Facing down Station Road, the range is partially screened by thick greenery.

Figure 103: The Railway Bell public house

Plevna Road

Plevna Road is one of the roads laid out towards the end of the 19th century on land between Thames Street and Station Road, linking the two roads. It is a fairly narrow, residential road secluded from the busy Upper Sunbury Road. The entrance from Station Road is flanked by nos.71 and 73, both stock brick with red-brick lintels and shopfronts with corner entrance doors. The houses along Plevna Road are all two storeys in stock brick under slate roofs, with some variation in design. The west side is comprised of terraces with a single storey canted bay window to the front and doors under either flat white painted lintels or brick overarches, except for the terrace at the southern end which just have tripartite sash windows to the ground floor. The eastern side is comprised of semi-detached pairs, the majority built to the same design with a ground floor canted bay window and pair of single-pane sash windows above. Each pair has a name plaque. Unsympathetic replacement windows, and the loss of a few canted bay windows altogether has disrupted the cohesiveness of the terraces/pairs. Low brick walls are the most common form of boundary treatment, but there is variation in colour and design.

104: 1 & 3 Plevna Road

Figure 105: Houses on the west side of Plevna Road

Figure 106: Houses on the west side of Plevna Road

Avenue Road

The second of the three roads, it is linked to Plevna Road by the short Varna Road. Similar in character to Plevna Road, it is comprised of two storey terraces. Both sides of the road are more continuous than on Plevna Road, with unbroken terraces. The majority of the eastern side is of the same design as those they back on to on Plevna Road, with a ground floor canted bay window and red brick door overarch. The western side of the road is of largely the same form, with the addition of a continuous slate roof at first floor with fishscale tiles. The shallow canted bay windows have an additional panel above, and simple mullions to the corners. Unsympathetic replacement windows, and the loss of a few canted bay windows altogether has disrupted the cohesiveness of the terraces. Boundary treatment varies, with low brick walls the most common, but picket fences are also present.

Figure 107: Houses on the east side of Avenue Road

Figure 108: Houses on the west side of Avenue Road

Belgrade Road

The third of the three roads between Station Road and Hampton Road, Belgrade Road was the last to be completed and features the larger, more substantial houses. The eastern side is comprised of two-storey early 20th century terraces, mostly rendered, with double height canted bay windows topped with gable ends, and paired central doors. At the southern end are two semi-detached, and a single detached house with single storey square bays to the front, timbered gables, and distinctive uneven glazing pattern. The western side is comprised predominantly of semi-detached red-brick pairs, with either square or canted single-storey bays and paired central entrance doors. The design varies subtly along the street, but all retain a similar form, height and materiality. Low brick walls are the most common form of boundary treatment, which variation in colour and style. No.10 has retained its original wrought iron gates and railings. A number of properties have retained their original black and white tessellated tile paths.

Figure 109: Houses on the east side of Belgrade Road

Figure 110: Houses on the west side of Belgrade Road

Rosehill, Beard's Hill & Oldfield Road

Rosehill is a prominent 18th century Grade II Listed stock-brick built house on the Upper Sunbury Road. The elevation overlooking Upper Sunbury Road is formed of three three-storey bays, with a central full height canted bay topped with a cupola flanked by a pair of chimneys. To the left is the single storey former coach house. Built for the celebrated 18th century tenor John Beard, it was purchased by the Urban District Council (UDC) in 1902 and used as Council Offices and Library until 1937 when Hampton Council was joined with Twickenham and Teddington, and the whole house was given over for use as the Hampton Library.

Figure 111: Rosehill

Figure 112: Lodge to Rosehill, and former Waterworks building

After the UDC purchased Rosehill, 56 ‘workmen’s cottages’ were planned and constructed between 1903 and 1904 on land to the north and west of the house, which are some of the earliest purpose-built council houses in the country. These houses form a U shape along Beard’s Hill, Oldfield Road, and Rosehill and are largely built to the same design, with some slight variation. Two separate terraces run along the eastern side of Beard’s Hill. Nos.19 – 28 are two storey cottages, with the ground floor in stock brick and the first floor in roughcast render, with red brick detailing under slate roofs. Nos. 19 and 28 (bookending the terrace) are topped with a shallow pediment with three ball finials. The original window pattern of a six-pane upper sash and two pane lower sash is retained, but in some cases with unsympathetic uPVC units. The original door design, with a pane of glass to the top third of the door and three vertical panels below, has been lost. Nos.1 – 18 were purpose built as flats, in the same style and materials as nos.19 – 28, but with paired central doorways under segmented arches each containing a further pair of doors angled in towards each other. The same glazing pattern is present, but the original door design features a glazed nine-pane top third, with a horizontal panel below and then two vertical panels. Palisade fencing is the common boundary treatment. The terrace along Oldfield Road is built to the same design as nos.19 – 28 Beard’s Hill, except for the original door design which is the same as nos. 1 – 18. A few unsympathetic porches have been added which disrupts the cohesiveness of the terrace, along with painting of the front elevation. The two terraces along Rosehill similarly match that at nos.19 – 28 Beard’s Hill, and contain a high proportion of original front doors. Nos. 1 – 9 Rosehill form the shortest and simplest terrace, without the pediments to either end. The contemporary development at the northern end of Rosehill contrasts markedly with the established character of the street.

Figure 113: Houses on Beard's Hill

Figure 114: Houses on Beard's Hill

Figure 115: Flats on Beard's Hill with example of the paired arched entrances with paired doors

Figure 116: Houses on Oldfield Road

Figure 117: Houses on Rose Hill

Oldfield Road is comprised of late 19th century two-storey semi-detached houses, in stock brick with red-brick detailing. Similar to those on Avenue Road, many are individually named.

At the corner of Oldfield Road and the Green are the Hampton War Memorial Cottages. These are four single storey, stock brick cottages with slate roofs splayed around the curved corner facing the Green. Funded by public subscription, they were dedicated on the 22nd April 1922.

Figure 118: 31 - 39 Oldfield Road

Figure 119: War Memorial Cottages

Views

Figure 120: View looking east along Station Road

Figure 121: View looking west along Station Road

Open Spaces

Hampton Village Green is not a traditional village green. The land it is on was historically the grounds of the 18th century Hill House. In 1901 the house was demolished to make way for the expanding Waterworks and filter beds were dug on the land between Station Road and Upper Sunbury Road, in-between the new Rose Hill and Belgrade Road. The filter beds were infilled in the late 1990s when the area was redeveloped for housing and part of the land was given over to forming a circular green. Today it is a wide, flat expanse of grass with a trees and benches around the edge and is a reminder of the impact of the Waterworks on the village.

Figure 122: Hampton Village Green

The Beveree Wildlife Site to the north of Station Road is a Site of Local Importance for Nature Conservation. It is a small area of mixed woodland, self-seeded fruit trees, scrub, two small meadows, and orchard trees. It is a secluded area of green open space tucked between the rear of Station Road and the early 20th century development on the former Manor House estate.

Figure 123: Beveree Wildlife Site

Street Furniture

Similarly to the rest of the village, street furniture is minimal and limited to LED lampposts and standard London bus stops/flags. The main shopping section of Station Road is busier, with a higher concentration of street furniture, including silver Sheffield stands, but the pavement is wider compared to elsewhere in the Conservation Area and the street furniture placed between the trees.

There is a Queen Victoria letterbox just past the World’s End public house, at the junction of Station Road and Warfield Road.

Figure 124: Bus stop and bin on Station Road, typical of the street furniture found elsewhere in the Conservation Area

Figure 125: Queen Victoria letterbox on Station Road

Character Area 4: Waterworks

Summary

Hampton Waterworks act as a landmark identifying Hampton from the river, as well as from the Upper and Lower Sunbury Roads when approaching from the west. These monumental mid- and late-19th century engine and pumping houses make a significant contribution to the character of Hampton, and the waterworks industry has considerably influenced the form of the western half of the village.

Architecture & Townscape

The Waterworks buildings lie to the west of the historic village core between the Upper Sunbury Road and the river. The area is largely unbuilt and dominated by the buildings themselves and the surrounding reservoirs and filter beds. This makes them highly prominent in views approaching from the east along Thames Street where they are an abrupt change from the village vernacular. All the buildings are Grade II Listed which reflects their architectural and historical significance.

Hampton Waterworks were established in the mid-19th century following the Metropolis Water Act of 1852, making it illegal to take drinking water from the then heavily polluted Thames. Hampton was identified as the first place upstream from Teddington Lock (the end of the tidal stretch of the Thames) which would be a suitable location to establish a waterworks facility. Three water companies: Southwark & Vauxhall, Grand Junction, and West Middlesex all established works at Hampton.

Constructed to largely similar designs in an Italianate style, the four large engine houses which comprise the Waterworks are all constructed in Gault brick and share similar features including large arched windows and decorative balustrades to the top.

The ‘Beam and Store Buildings’ are the westernmost surviving Waterworks building and also one of the oldest. Designed by Joseph Quick for the Grand Junction Waterworks company and built between 1853 and 1855 they were later extended in 1881-2 by Alexander Frazer.

Figure 126: The Beam and Store Buildings

The Ruston Building immediately to the west was also designed and built by Quick between 1853 and 1885, for the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company. The western block was added in 1881-2 by J.W. Restler.

Figure 127: The Ruston Building

The Waterworks site was enlarged in the 1860s and the Morelands engine house constructed between 1867 – 1870, also by Quick for the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, and extended and completed by Restler in 1885 – 6.

Figure 128: The Morelands Building

The last engine house was the Riverdale building, constructed between 1898 and 1900 for the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company. This closed the space between the village and the Waterworks, which until now had existed on the western periphery of the village. The Waterworks Gatehouse on Thames Street was also completed at this time, which served to link the Waterworks and the village even more closely.

Figure 129: the Riverdale Building

Between the Ruston and Beam buildings, and beyond the Beam buildings on the western edge of the Conservation Area are three pairs of ‘Waterworks Cottages’. Built alongside the first of the engine houses in the 1850s, the cottages are dwarfed by the scale of the Waterworks, but have a close visual and historic relationship.

Figure 130: Waterworks Cottages, 6 - 9 Upper Sunbury Road

The construction of the Waterworks had a significant impact on the village, with the loss of land and access to the riverside to the west. The establishment of further filter beds between Belgrade Road and Rose Hill in the early 20th century led to the Waterworks dominating the southern and western sides of Hampton. These filter beds were drained in the late 1990s and redeveloped into the Village Green and houses.

The Waterworks complex is currently undergoing redevelopment to preserve the former engine houses and find new uses for them.

Views

Thames Street curves around as one proceeds west along it, resulting in the Waterworks gradually becoming visible before an abrupt end in the historic village core past nos.54 and 56 Thames Street, where further views west along the Upper Sunbury Road become dominated by the Waterworks to the south. Views approaching the Waterworks and Hampton from the Lower Sunbury Road allow for a full appreciation of the scale of the buildings.

Figure 131: View looking west from Thames Street towards the Waterworks

Figure 132: View of the Ruston and Beam Buildings from Lower Sunbury Road

Figure 133: View of the Morelands Building from Lower Sunbury Road

Street Furniture

The cast-iron railings in front of the Waterworks Buildings are all Grade II Listed, forming an integral part of the streetscape and contributing to the large-scale, industrial character of the area.

Part 3: Management Plan

Summary

This Appraisal has assessed the quality and condition of the Hampton Village Conservation Area. Several site visits were undertaken in October 2022, where the area was observed and photographed.

The Appraisal has summarised the strengths and weaknesses of the Conservation Area, and this management plan sets out a strategy to consolidate and enhance these strengths and prevent further erosion of the area’s special architectural and historic character.

Modern development has diluted the historic character of the village in some places and reduced the cohesiveness of the historic streetscapes. The busy roads sever the historic relationship with the river and undermine the tranquil, riverside/suburban setting. There is wide variation in the quality of architecture, with many fine Listed 17th and 18th century buildings alongside some less-well preserved smaller 18th and 19th century buildings.

However, the historic character along the main streets continues to display a sense of depth and identity, as well as contributing elements of interest and high-quality architecture. The piecemeal development of the area is still very much in evidence due to the variety of architectural styles.

The overall conclusion of the Appraisal is that all areas of the Conservation Area are worthy of inclusion. It is hoped that this clearer, more extensively illustrated Appraisal will assist the Development Management Process in making more informed planning decisions in respect of the area’s character.

Furthermore, it is apparent that any further deterioration would endanger the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. An Article 4(2) Direction is in place comprising specific properties on Station Road, Avenue Road, Rosehill, Oldfield Road, and Beards Hill (see below).

Under Section 71 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, local planning authorities have a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of conservation areas in their area, from time to time. Regularly reviewed appraisals, or shorter condition surveys, identifying threats and opportunities can be developed into a management plan that is specific to the area’s needs.

Article 4(2) Direction

Conservation Area designation does not in itself introduce any greater level of statutory control over minor works to properties, such as the demolition of original features, the replacement of windows and doors, the loss of garden fences, or other boundary treatment. Such works are normally ‘permitted development’ for homeowners and no application for planning permission is normally required, despite the impact these works can often have on the appearance of an individual property and consequently the impact on the overall character of the Conservation Area.

Local Planning Authorities, however, have power to control these changes by removing certain permitted development rights by making an Article 4 Direction. Once a direction has been made, planning permission is required for those classes of development listed. Such directions only affect unlisted dwelling houses in single occupation (i.e. not subdivided into flats, or with individual rooms let to tenants) and only those elevations that front a highway, waterway, private street, or other publicly accessible space (including side elevations of corner properties). Flats, shops, offices and other commercial buildings and houses in multiple occupation do not have the benefit of permitted development rights and so planning permission for changes is required.

There is one existing Article 4(2) direction within the Conservation Area. It was made on the 26th October 1992.

Article 4(2) Restrictions Schedule

i) The erection or construction of a porch outside any external door of a dwelling house.

ii) Change of materials to roofs and walls and painting of brickwork of any façade.

iii) Any alteration to the roof of a dwelling house.

iv) Any alteration to windows including frames, glazing bars and cills.

v) Any alteration to external decorative details other than the painting of wooden surfaces.

vi) Any other structural alteration which would result in the removal (or partial removal) of chimney stacks; removal of, alteration of or addition to balconies, porches, canopies, and external doors.

vii) Alterations to or rebuilding of walls, fences, and gates.

viii) Installation, alteration or replacement of satellite antennae on dwelling houses or within the curtilage of dwelling houses.

Applies to the following addresses:

- Station Road Nos. 51 – 61 (odd)

- Avenue Road Nos. 10 – 30 (even)

- Avenue Road Nos. 25 – 31 (odd)

- Rosehill Nos. 1 – 9 (odd)

- Rosehill Nos. 2 – 40 (even)

- Oldfield Road Nos. 1 – 23 (odd)

- Beards Hill Nos. 1 – 28 (inclusive)

Problems and Pressures

- Loss of traditional architectural features and materials due to unsympathetic alterations.

- Loss of original windows and replacement with unsympathetic styles and materials.

- Good quality original shopfronts have been altered by the removal of historic features or additions of new poor-quality ones, addition of inappropriate features such as disproportionate signage, and loss of detailing such as plinths, stall risers, pilasters, and inset doorways.

- Inappropriate materials used for pointing to brick boundary walls, leading to degrading walls and damage to the brickwork.’

- Heavy traffic through the village, especially on Thames Street, Church Street and High Street.

- Traffic volume and its associated noise, danger, and pollution creates a relatively poor pedestrian environment.

- Bell Hill Recreation Ground is an under-utilised area, dominated in part by cars.

- The Triangle is dominated by heavy traffic which results in an under-utilised small area of hardstanding occasionally mounted by cars.

- The increasing privatisation of the riverside has reduced accessibility to it and led to a loss of connection between the village and the river.

- Modern, less sympathetic buildings sometimes undermine the historic character of the village core and reduce the cohesiveness of the streetscape.

- Notable visual detractors:

- The telephone exchange on High Street

- 29 – 31 Station Road

- 92 – 100 Station Road

Opportunities for Enhancement

- Preservation, enhancement, and reinstatement of architectural quality and unity.

- Encourage the replacement of unsympathetic windows with sympathetic windows in both material and form.

- Encourage improvements to the quality and design of shopfronts.

- Encourage the repair and restoration of damaged/degrading brick walls with appropriate materials.

- Public realm improvements to Bell Hill to encourage greater usage and resist further car dominance.

- Public realm improvements to the Triangle to emphasise its position at the apex of the roads forming the historic village core.

- Public realm improvements to the junction of Church Street and Thames Street, including improved paving and possible tree planting.

- Maintenance of historic items of street furniture to ensure their retention and contribution to the street scene, including the historic railings on Thames Street.

- Ensure that new development respects the character of the area and is well-designed with high-quality materials.

- Encourage an appropriate, high quality infill development adjoining the former Police Station on Station Road.

Design Guidance

This Appraisal is also a source of guidance for applicants seeking to make changes that require planning permission, helping to make successful planning applications.

The advice below sets out guidance which encourages good quality of design which will help to both preserve and enhance the character of the Conservation Area.

Dwellings within Conservation Areas which have been divided into flats do not benefit from Permitted Development Rights, requiring planning permission to carry out alterations and extensions.

It is worth noting that full planning permission for any alteration to a shopfront that would change the shop’s appearance must be applied for. This includes replacement shopfronts, installation or replacement of doors and windows, and installation or replacement of external security measures. The installation of a new shopfront, or the significant altering of an existing shopfront is also development which requires planning permission.