Richmond Green

Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation Area no.3

Figure 1 Painting of Maids of Honour Row, 1901

Contents

- Introduction

- Statement of Significance

- Location and Setting

- Historical Development

- Architectural Quality and Built Form

- Management Plan

1. Introduction

Purpose of this document

Richmond Green Conservation Area is closely linked in terms of its history and development with two adjacent Conservation Areas - Richmond Riverside and Central Richmond– and this Appraisal Document should be considered in the context of the special relationship between them. The Appraisals for each Area can be viewed by clicking their respective names above.

The principal aims of conservation area appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications;

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area;

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication titled Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78). Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to local conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan and national policies outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the London Plan. Our overarching duty, which is set out in the Act, is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

Conservation Areas SPD![]() (pdf, 653 KB)

(pdf, 653 KB)

Buildings of Townscape Merit

Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) are buildings, groups of buildings or structures of historic or architectural interest, which are locally listed due to their considerable local importance. The policy, as outlined in the Council’s Local Plan, sets out a presumption against the demolition of BTMs unless structural evidence has been submitted by the applicant, and independently verified at the cost of the applicant. Locally specific guidance on design and character is set out in the Council’s Buildings of Townscape Merit Supplementary Planning Document (2015)![]() (pdf, 895 KB), which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

(pdf, 895 KB), which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

What is an Article 4 Direction?

An Article 4 Direction is made by the local planning authority. It restricts the scope of permitted development rights either in relation to a particular area or site, or a particular type of development anywhere in the authority's area. The Council has powers under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 to remove permitted development rights.

Article 4 Directions are used to remove national permitted development rights only in certain limited situations where it is necessary to protect local amenity or the wellbeing of an area. An Article 4 Direction does not prevent the development to which it applies, but instead requires that planning permission is first obtained from the Council for that development. View further information about Article 4 Directions to check if any permitted developments rights in relation to a particular area/site or type of development apply in your area.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Richmond Green Conservation Area was designated on the 14th January 1969.

It was subsequently extended on the 7th November 2005.

Following approval from the Environment, Sustainability, Culture and Sports Committee on the 21st June 2022, a public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between the 4th July and 1st September 2022.

This Appraisal was adopted on the 20th November 2023.

Map of Conservation Area

2. Statement of Significance

Richmond Green is predominantly characterised by the large central green, an open space with a tranquil residential character. The main Green is flanked by two smaller open spaces, Little Green and Old Palace Yard, which contribute to this character. Together, they provide a welcome contrast from the busy town centre and are used year-round by visitors and residents alike. The Green is surrounded by a concentration of properties of particular architectural and historic interest dating from the late-15th century through to the late-20th century, the status of the area established by the construction of Richmond Palace, the remains of which are located to the southwest of Richmond Green.

Richmond Theatre, Maids of Honour Row, and Palace Gate House are important architectural contributors to the Green, while Little Green is defined by Richmond Theatre and Richmond Library, which lend a distinct character.

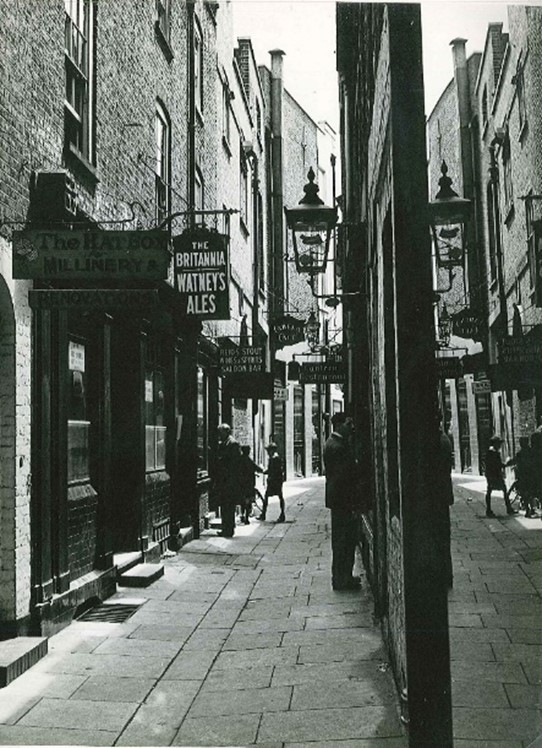

Several small lanes, some dating from the early development of Richmond – Brewers Lane, Golden Court, and the Market Passage – provide a refuge from traffic and are spaces of a more intimate nature. The lanes to the southeast of The Green, including Paved Court and Golden Court, are lined with small businesses and boutique shops that add a commercial dimension to the character of the Green. They remain largely residential on the upper floors.

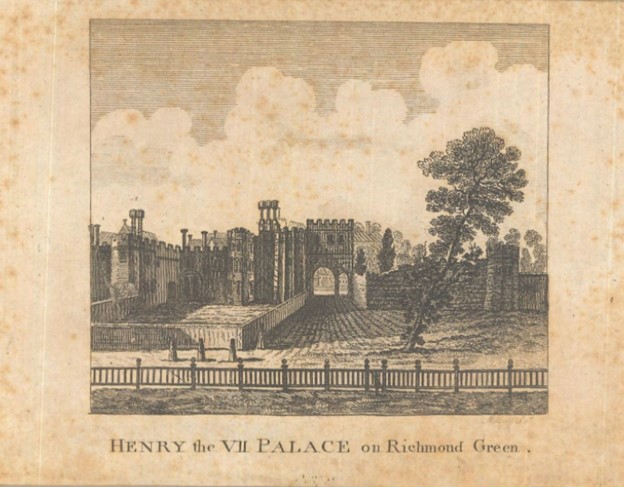

Figure 2 Drawing of Richmond Palace, 1750

3. Location and Setting

General character and plan form, e.g. linear, compact, dense or dispersed; important views, landmarks, open spaces, uniformity.

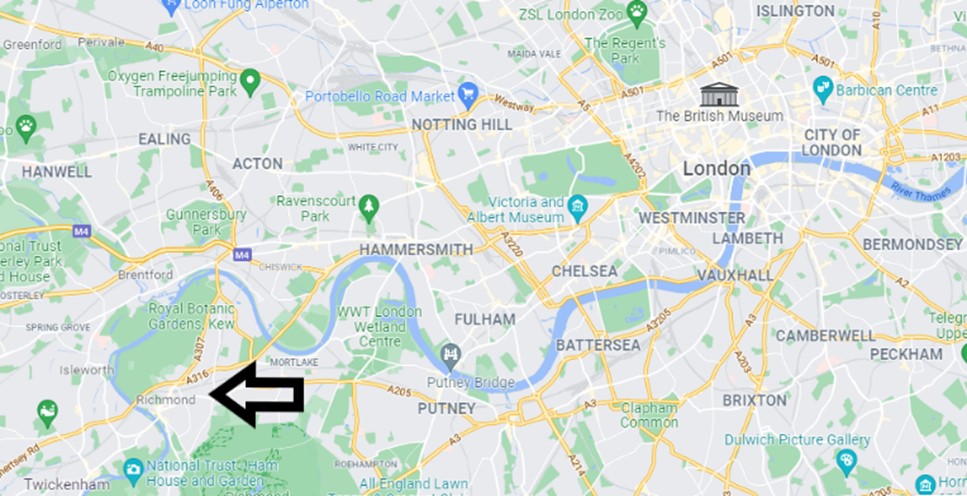

Situated to the south west of London, Richmond lies between two significant areas of green space: The Old Deer Park/Kew Gardens to the north, and Richmond Park and Ham lands to the south. It is north east of Twickenham, north of Ham, south east of Isleworth, south west of Chiswick and west of Putney.

Figure 3 Aerial map showing Richmond in wider context

Figure 4 Map showing Richmond in wider context

The Conservation Area lies in the centre of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, and although it has its own distinct character, it shares a relationship with both the Central Richmond Conservation Area and the Richmond Riverside Conservation Area, and this context should be considered when studying any of the three. To a lesser extent, there is also a shared relationship with the nearby Old Deer Park Conservation Area.

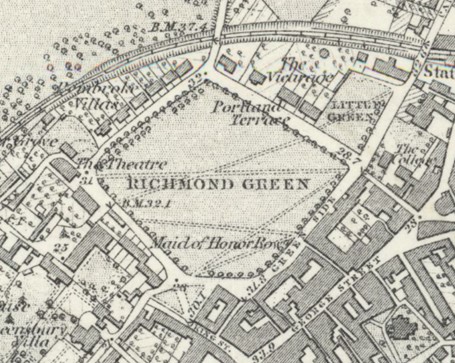

Richmond Green Conservation Area adjoins Central Richmond to the west of George Street. Behind the busy commercial thoroughfare, the Green is a large open space bordered with trees and residential properties. At the south-east corner are some small commercial premises largely confined to Paved Court, Golden Court and Brewers Lane. The Little Green sits at the north-east corner of Richmond Green.

Richmond Green is owned by the Crown Estate and leased to the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It is roughly 12 acres in size and generally consists of open grassland, bordered by broad leafed trees.

Topography

The Area is largely flat which allows for long views across the Greens and both into and from the Conservation Area to the surrounding areas. There is a slight slope to the south side of the Area, particularly to Old Palace Yard, where the ground begins to descend towards the Thames.

Figure 5 Aerial map of Richmond Green

4. Historical Development

Stages/phases of historical development and historic associations (archaeology etc.), which may be influencing how the area is experienced.

The history and development of the Conservation Area is fundamentally linked to the history and development of the adjacent Conservation Areas of Central Richmond and Richmond Hill. As such, much of the information below is applicable to all three Areas, and it is valuable to consider these Appraisal documents concurrently with Richmond Riverside.

The growth of Richmond has been physically constrained by the large open spaces of Richmond Park and Petersham Common to the south and south-east, the River Thames to the west and the Old Deer Park to the north, later reinforced by the railway and A316 trunk road. Thus, throughout its development the town has only really been able to expand east and north-east.

The town’s history, and indeed its existence, is dominated by and owed to the medieval and Tudor royal manor and palace. It was not a medieval town as it was never granted a market or fair, and before 1501 it was known as Shene. The first record of the manor house of Shene was in the 12th century when it belonged to Henry I, who stayed there in 1126 and granted the manor to the Belet family. The settlement of Shene presumably gradually developed around the manor house and succeeding palaces but little is known of its role and layout, Given the regular visits by royalty, their courtiers and other high status visitors Richmond/Shene is unlikely to have been a typical medieval village.

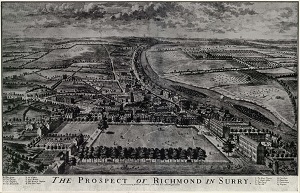

The early medieval manor house was demolished by Richard II after the death of his Queen, and a new palace was built by Henry V &VI. After a fire in 1497 the palace was rebuilt by Henry VII, and from 1501 the village of Shene came to be known as Richmond as Henry VII was the earl of Richmond in Yorkshire. The accession of the Stuarts saw the creation of the New Park (now the Old Deer Park) by James I from 1603 and Richmond Park by Charles I from 1634. The civil war and execution of Charles I in 1649 led to the sale and quick demolition of most of the palace, with Trumpeters’ House (1702-4), Old Court House, Wentworth House and Maids of Honour Row (1724-5) gradually being built on the site of the palace during the 18th century. However, the Gate House and associated walls and the Wardrobe survive.

Charles I brought his court to Richmond in 1625 to escape the plague. This resulted in the development of Richmond Green as it became the home of court attendants, diplomats and minor nobility. The popularity of the Green persisted after the demolition of the palace.

Richmond Green has a long association with sporting events, with jousting tournaments and archery taking place from the 16th century and cricket from the mid-18th century to the present day.

Archaeology

Most of the Conservation Area is, along with Central Richmond CA and part of Richmond Riverside CA, within Richmond Archaeological Priority Area (APA) 2.6 - Richmond Town, a Tier II APA. Tier II ‘indicates the presence or likely presence of heritage assets of archaeological interest.’ Part of the Conservation Area is also within APA 1.4 – Richmond Palace, a Tier I APA. Tier I is defined as an area which is known, or strongly suspected, to contain a heritage asset of national significance (a scheduled monument or equivalent); or is otherwise of very high archaeological sensitivity.

Shene/Richmond was neither a normal small market town nor a typical rural village. Its association with royal court and high-status visitors will likely have resulted in the provision of distinctive buildings, facilities, material culture, and foodstuffs. There is, therefore, potential for the Archaeological Priority Area to contain deposits of medieval and post-medieval date that relate to this development. Its significance lies within its potential to provide insight into settlement change, land use, domestic, and commercial aspects of life, and changes in lifestyle around the palace. It has the potential to inform understanding of local, community heritage assets, as well as nationally significant sites of Richmond Palace and the Shene Charterhouse.

From the 1690's Richmond began to develop from a small village into a small town. Along the alignment of George Street post holes and beam slots which pre-date the 18th century, as well as ditches and a well dating from the 17th or 18th century have been recorded. As Richmond became a fashionable and popular resort, the palace site and Richmond Green developed into exclusive residential communities. There are many statutorily listed buildings within the town which date from the early 18th century, including those at Old Palace Terrace. Many houses surrounding Richmond Green were built to accommodate people visiting or working in the Palace Maids of Honour Row was constructed in 1726 as

lodgings for the maids of honour attending the Princess of Wales who, with her husband, the future George II, lived in a house in the Old Deer Park. In the mid-19th century, the construction of the railway that cuts Richmond Town off from the Old Deer Park subsequently led to the development of Victorian villas inhabited by wealthy London commuters, including the renowned explorer Sir Francis Richard Burton.

Richmond Green is an important urban green and open space of local historic and cultural significance having provided a place for cultural activity from jousting in the medieval period to cricket in the modern. It is an urban green located to the north of the Richmond Palace site. To the north-east lies a smaller open space called Little Green. Richmond Green has been in use since medieval times when it was used for palace activities including jousting and archery contests. The Green had also been used for pasture prior to the 18th century after which time it was used for social activities like Cricket. It has been retained as an undeveloped open space and so there is potential for new discoveries such as ancient watercourses.

Figure 6 Drawing of Richmond Palace

The village gradually developed into a town due to the presence of the palace, and decline followed its demolition. Prosperity returned towards the end of the 17th century as Londoners fled the plague, and the discovery of a spring led to Richmond becoming a popular spa town over the following century.

Figure 7 The Prospect of Richmond in Surry, published by Overton and Hoole in 1726, illustrating The Green, Little Green, and surrounding development.

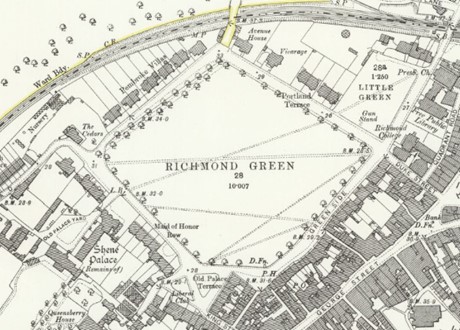

Figure 8 OS map, 1860s

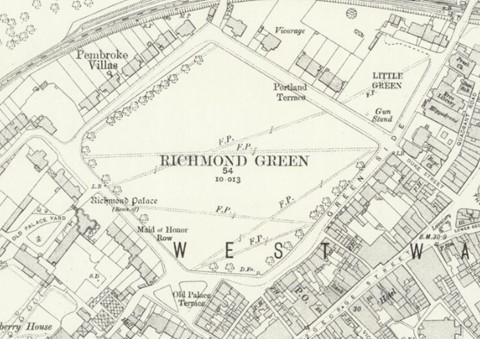

Figure 9 OS map, 1890s

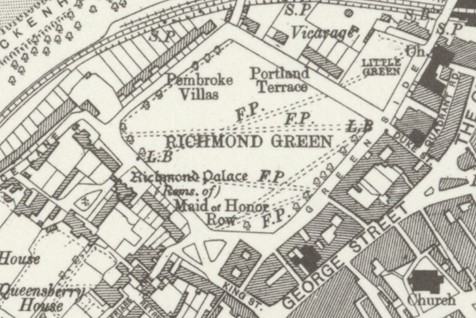

Figure 10 OS map, 1910s

Figure 11 OS map, 1930s

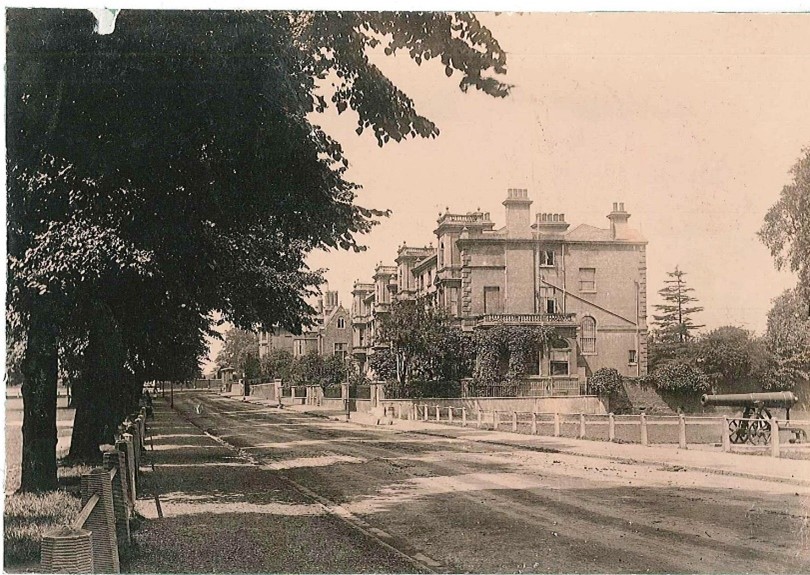

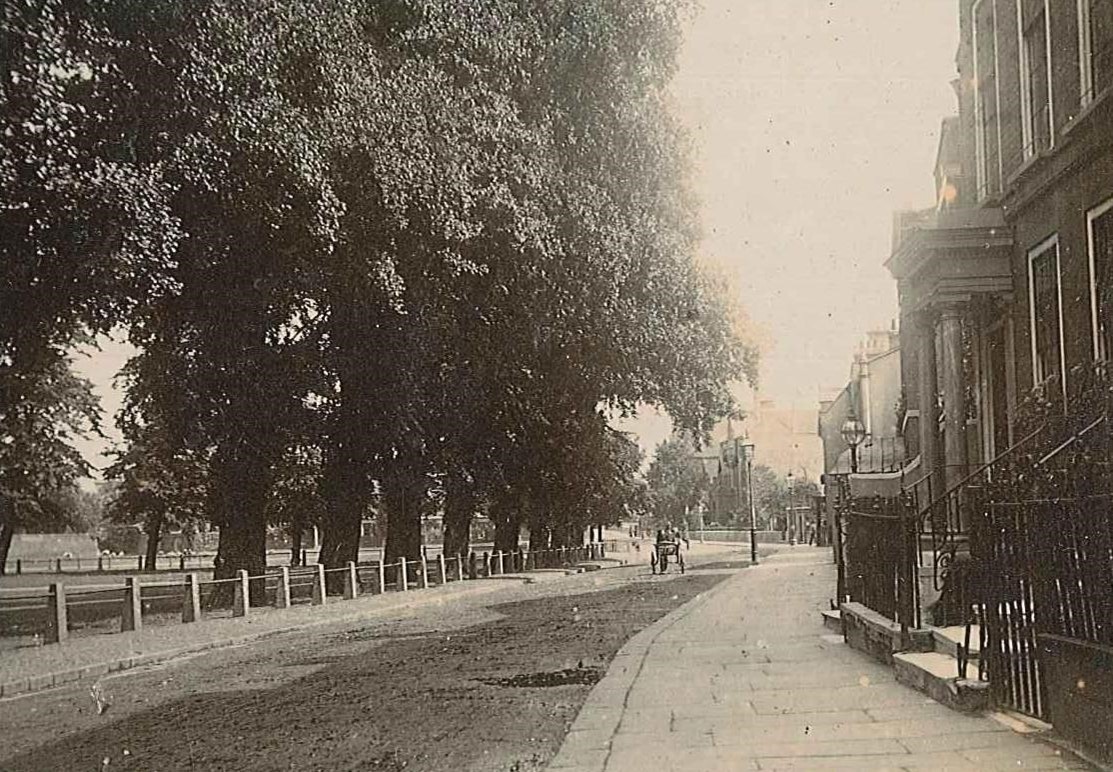

Figure 12 Portland Terrace, c.1890

Figure 13 View along The Green in gront of Pembroke Villas, c.1900s

Figure 14 The Green, showing original cast iron bollards c.1900s

Figure 15 Old Palace Place as The British Red Cross Hospital, 1918

Figure 16 Painting of the Green, 1905

Figure 17 Maids of Honour Row, 1902

Figure 18 Gatehouse to Richmond Palace, c.1900

Figure 19 Painting of Richmond Green, close to Pavement Court, 1901

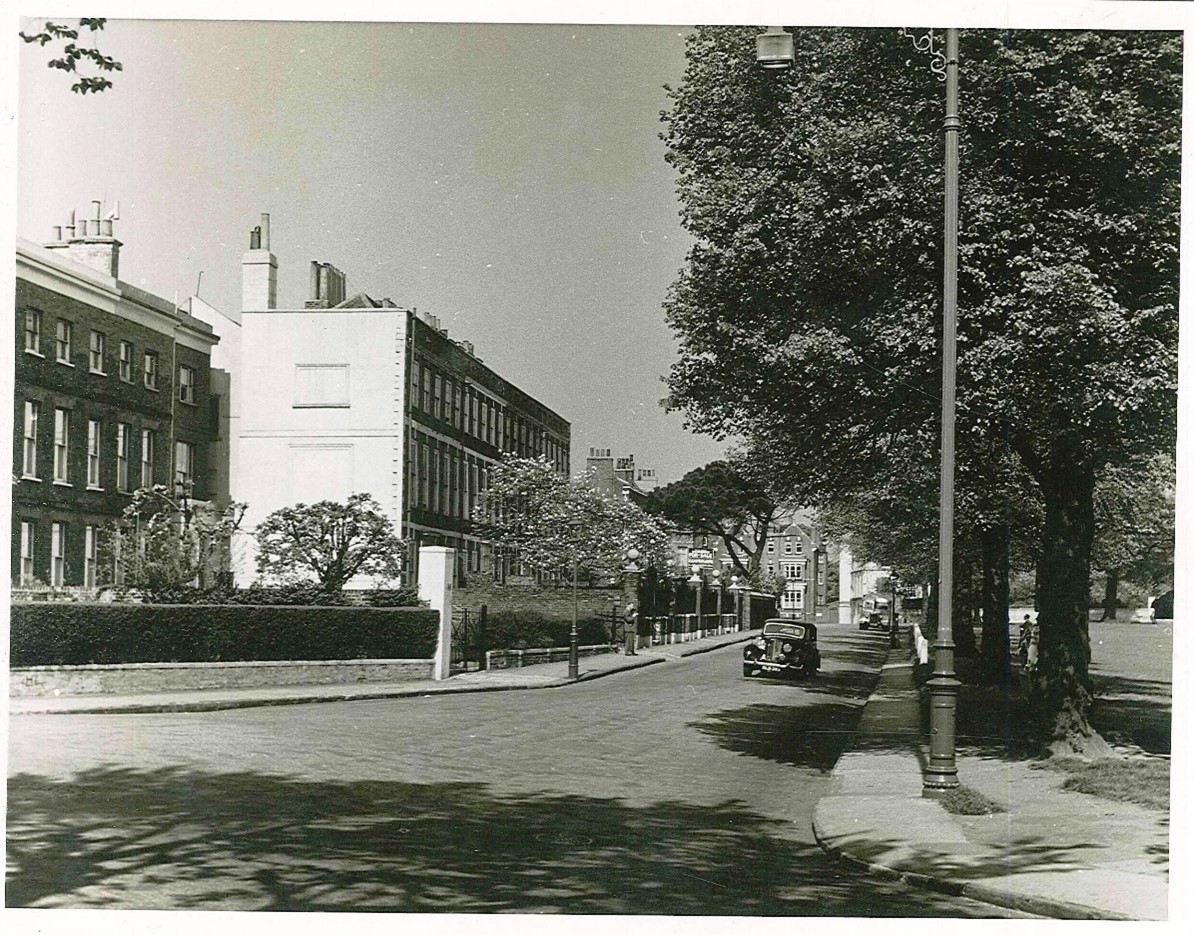

Figure 20 Maids of Honour Row, 1952

Figure 21 Brewers Lane, c.1940s

Figure 22 Paved Court, 1902

5. Architectural Quality and Built Form

The Richmond Green Conservation Area has at its heart an urban green, which has medieval origins, which Niklaus Pevsner describes in 'Buildings of England' as 'one of the most beautiful urban greens surviving anywhere in England'. It is surrounded by substantial houses of exceptionally high quality and is of great historic importance due to its connections with the long since demolished royal palace and the Old Deer Park.

The Green provides a large public open space, an important recreational asset which is a pleasant visual contrast to the dense urban fabric of the town centre.

There are three distinct main elements to the Conservation Area, which will be explored in further detail below, but each element is closely related and united around The Green, contributing to the overarching character and appearance. The main part of the area is the Green itself and the development which surrounds it, including the remains of Richmond Palace, and the small area adjacent to this at Old Palace Yard. The Green is complemented by the smaller and more secluded Little Green to the north-east, and the small two contained triangles in front of Old Palace Terrace to the south-west. Maids of Honour Row front gardens, Richmond Green, and Little Green are included in the London Gardens Trust Inventory as being of historic interest.

First impressions of the Green are of an elegant urban green entirely enclosed by buildings. Closer inspection reveals that whilst all sides of the Green share characteristics in terms of building materials and scale, each side is quite different in architectural form and townscape. The southern part of the Green tends to be the busiest, with a number of pubs, restaurants and shops in close proximity to one another.

Character area 1 - The Green

Figure 23 View of The Green

Figure 24 View of Pembroke Villas from the Green

Figure 25 View of Portland Terrace from the Green

Figure 26 View of the Green bordered by trees

Figure 27 View of Richmond Green

Townscape and Landscape

The main, central portion is a huge level open space with uninterrupted views across its wide expanse and a fittingly spacious setting for the fine houses surrounding it. The avenues of mature trees provide shade in summer and a more secluded alternative to the road for pedestrians.

The character of the Green varies seasonally as the colour, shape and leaf cover of the trees change. During the summer the formality of the Green is softened by the trees, which become the dominant element in the landscape.

Views of the buildings remain though, under the tree canopy and occasionally to chimneys and roofs over the tree line. When the trees are in leaf, the dense vegetation turns the perimeter road into a separate linear space and whilst the Green becomes a softer landscape, the road and buildings lining it take on a stronger urban character.

The most common tree species for the avenues is lime, although on the north-east and south-west sides the inner rows have been planted with Norway maple, and on the south-eastern side, replanted with a single row of large London Planes, although along a different alignment to the historic trees they replaced.

Characteristic of the Green are the long straight paths, following apparently random but ancient routes, creating triangle and diamond shapes. Of note is the historic avenue of trees extending along the north-western side of The Green’, parallel with Pembroke Villas, known as ‘The High Walk,’ which has been impacted by post-war replacement planting. Little built form intrudes into the sky above the surrounding buildings, emphasising the inward looking, almost isolated feel of the space. The landmark spire of the distant Church of St. Matthias is an attractive exception.

Figure 28 Borders of the Green with mature tree planting

Figure 29 Car parking along the boundary of the Green

Parked cars are visible all around the Green and viewed from the centre do not affect its character. However, oblique views of the buildings from the perimeter road reveal that the parked cars can have a negative on the townscape.

Buildings

Figure 30 Buildings to south east side of the Green

The south-east side of the Green, commonly known as 'Green Side', consists of mainly late 17th and early 18th century terraces of townhouses. Although most properties are three storeys high, overall building heights vary widely creating a broken eaves and ridge line, which is enhanced by a number of impressive chimney stacks.

Some of the oldest surviving buildings on this side of the Green are situated next to the junction with Duke Street, including no.1 and no.3 with its later Gothic frontage.

This side of the Green includes a small number of pubs and shops, especially where the alleys and streets emerge from the town centre. Many of the houses are currently used as offices and this gives a commercial as well as residential element to its character and generates a level of activity not found elsewhere on the Green.

Figure 31 Maids of Honour Row

The south-west frontage facing the Green is less uniform, but the buildings are of an equally high quality. A key element of the character of this frontage is the changing visual experience as one moves along the road, due to the differing building lines, garden sizes and tree cover. Maids of Honour Row is the most dominant element in the frontage; a fine 18th century terrace, closest to the road, it acts as a centre piece in the street frontage. The formal three-storey composition is characterised by being divided into four properties of plum brick construction with red brick dressings surrounding the Georgian windows. The skyline is interrupted only by four chimney stacks of monumental scale, which create a strong silhouette when viewed from the Green. Their front gardens and boundary walls and railings add further character to the street and form a visual link to the Green.

Figure 32 Gate house of Richmond Palace

Adjacent is the Gate House, built of red brick with battlemented towers. This area is of immense historical and archaeological importance as the Gate House itself, some boundary walls and The Wardrobe to the rear incorporate the only standing remains of King Henry VII Richmond Palace of 1501. The small gateway with stone arch offers interesting views into the yard towards Trumpeters' House. The lower building height of the Gate House gives the canopy of the impressive Stone Pine in the front garden a strong silhouette, especially in the winter months. The Maids of Honour Stone Pine is listed as one of the 'Great Trees of London'. Of particular importance to both the south-east and south-west sides of Richmond Green is the constantly changing level of detail revealed to the onlooker on approach towards the buildings from the Green, the overall pattern of windows and rooflines gradually giving way to the intricate detail of individual elements such as decorative door cases and ironwork.

Beyond, Old Palace Yard is a peaceful and secluded open space of high townscape and architectural quality, with buildings such as Trumpeters House and the Wardrobe focused around a small central green. With only two entrances from the footpath and an archway onto the Green, the Yard has a somewhat exclusive and private feel, with signs at the Green entrance which dissuade people from entering. The Yard also serves as a means of accessing Old Palace Lane and the River Thames to and from The Green.

The north-west side of the Green was not fully developed in its current form until the mid-19th century. In contrast to the more continuous buildings on the south-east and south-west sides, this side is dominated by Pembroke Villas, five pairs of semi-detached villas in an Italianate style of mainly two to three storeys with stucco ground floors and stock yellow brick to upper floors with impressive round arched entrance porches. In many cases the front boundary walls have been lost or altered unsympathetically to accommodate car parking spaces, weakening the boundary definition.

Figure 33 1 Pembroke Villas

Vital to the character of this side of the Green are the gaps between the villas, which allow a backdrop of sky and treetops to appear between each pair, though most have now erected modern side extensions. A large single lime tree ensures a sense of enclosure in front of the much smaller, rather suburban scaled properties in Garrick Close, the high walls of The Virginals also providing strong definition to this corner of the Green.

The north-east side of the Green is the least coherent in terms of building typology and contains some of the most recent buildings. A simple yet interesting terrace of modern three-storey town houses forms the longest element of the frontage. High front garden walls are uncharacteristic of the Green, though the boundary and homogeneity of the terrace is softened by trees and greenery.

Figure 34 Darbourne & Darke houses in Portland Terrace

Figure 35 1-4 Portland Terrace

Figure 36 The Prince's Head Public House

Figure 37 Pair of K6 telephone boxes

Figure 38 Paved Court

Figure 39 Victorian drinking fountain (Grade II)

1-4 Portland Terrace, two pairs of mid-19th century Italianate stuccoed villas (grade II listed) of three storeys plus basement form a fine element in the townscape and visually dominate this side of the Green. The projecting towers at each end with pediments and cornices, along with grand side entrances, enrich the details. The remainder of this side of the Green consists of mature rows of mature lime trees, which maintain the enclosure separating the Green from Little Green.

The south-east elevation is separated from the adjacent buildings by Paved Court, a narrow alley of York stone lined with small shops. This, together with Brewers Lane, is one of the most picturesque alleys in the town centre, containing many good quality shopfronts. Leading from King Street it emerges into a small open space by the Prince’s Head Public House. This is a diverse space, with activity from nearby shops and outdoor pub seating; street trees, as well as Grade II listed red phone boxes and a Victorian drinking fountain. The quality of the buildings facing it give the space a human scale and a degree of tranquillity.

Character Area 2 - Little Green

Figure 40 Little Green

Figure 36 View from Little Green toward the Green

Townscape and Landscape

The Little Green is less formal than the Green, and its small size and mature trees give it a more intimate feel, a closer relationship existing between the space and buildings around it. A civic element to the character of Little Green is provided by the varied frontage of the former church, theatre and library facing it, in contrast to the residential areas around the sides of the Green.

Buildings

Figure 42 1-3 Little Green

The buildings on the south-east side of Little Green continue the built frontage of the terraces on the Green but are mainly public buildings rather than shops or offices. They are also more monumental, imposing and individual in character than the groups of buildings on the Green, and the key contribution that they make is as a varied and architecturally interesting group element in the townscape.

Figure 43 Onslow Hall

At the corner with Duke Street is a notable late 19th century office, formerly educational turned office building with distinctive decorative stucco and portico, and a sensitive modern extension on the Duke Street frontage. Set back from the road behind railings is the impressive Onslow Hall.

Richmond Theatre, 1899 (grade II*), is a most impressive exuberantly detailed building of red brick and buff terracotta, designed by Frank Matcham, with a grand projecting entrance with steps flanked by twin towers. Above the entrance is a decorative arch and pediment and twin copper domed towers, a landmark from some distance. In contrast is the comparatively restrained lending library in soft red brick with solid stonework dressings.

Figure 44 Richmond Theatre

Adjacent is a more domestically scaled two-storey building, which was formerly a private residence but now also part of the library. It has decorative gables and bay windows at each end and timberwork detailing. At the corner of the Green is the former United Reformed Church, now residential use, an imposing Gothic building with two huge lancet windows and thick buttresses ending in pinnacles making it one of the more prominent buildings on the Little Green.

Figure 45 Former United Reformed Church, Little Green

The north-west and south-west sides of the Little Green are defined by tree planting, reinforcing the enclosure of the space. The north-west side is the most open in aspect, consisting of the side elevation and garden walls of Portland Terrace. The tree line here is less substantial though the trees in the gardens of Portland Terrace are important in maintaining the enclosure of the space. On the north-east side of The Green, a short terrace of three fine listed town houses marks the gateway into The Green from Parkshot along with the Church. Their front boundary walls have all but disappeared to provide car parking space, thereby weakening the boundary definition.

Character Area 3 - Old Palace Place/ Terrace

Townscape and Landscape

Figure 46 View of Old Palace Place

Figure 47 Old Palace Place

Figure 48 Cycle stands, Old Palace Terrace

The small square in front of Old Palace Terrace has the character of a small intimate suburban green space. However, the road bisects the space, and due to the traffic and parked cars the grassed areas have little recreational use although they are visually important. Mature trees add character and definition to the space.

Buildings

The south-east and south sides of the square are characterised by terraces of listed town houses, ensuring a strong urban edge of very high-quality townscape. The block of which Old Palace Terrace forms a part is well defined and of exceptionally high-quality townscape. The south-east elevation is separated from the adjacent buildings by Paved Court, a narrow alley of York stone lined with small shops. This, together with Brewers Lane, is one of the most picturesque alleys in the town centre, containing many good quality shopfronts. Leading from King Street it emerges into a small open space by the Prince’s Head Public House. This is a diverse space, with activity from nearby shops and outdoor pub seating; street trees, red phone boxes and a Victorian drinking fountain. The quality of the buildings facing it give the space a human scale and a degree of tranquillity.

Figure 49 Old Palace Terrace

The north-west side of this green space is less well enclosed, consisting only of the side elevation of 45 The Green, its boundary wall adding definition to the square and enclosure at a more pedestrian scale. The row of lime trees on the north-east perimeter of the Green to the north-east, gives a strong sense of enclosure to the space but allows good views across the main Green to the prominent Portland Terrace.

Routes into the Green

Despite its enclosed character, the Green is far more permeable than initial impressions suggest. Though there are eleven routes into the Green, the dense urban form of the town centre prevents any longer views into it. The contrast between the narrow courts and the wide, open space, and the 'surprise' elements, is one of the townscape highlights of the Conservation Area.

Brewers Lane, one of the earliest streets in Richmond to be built and named, has no association with brewing, but was named for a William Brewer who had a cottage there in 1576. This paved passageway links the Richmond Green Conservation Area to George Street in the Central Richmond Conservation Area, and has a number of listed buildings from the eighteenth century.

Brewers Lane, along with Golden Court and Paved Court, have particular architectural, spatial, and townscape character within the Area. Not only do they serve as important access routes, but as transitionary routes from the commercial town centre to the more tranquil character of The Green. Fittingly, the narrow passages are lined with shops and cafes which offer active frontages, and many are housed in historic buildings with surviving historic shopfronts.

Figure 50 Brewers Lane

In a similar way, the close proximity of the Green to the River Thames is not immediately apparent to the casual observer. Old Palace Lane and Friars Lane are historic routes connecting the river to the Green and both have bends that ensure there are no direct views between either features, which provides a pleasant element of surprise in the townscape. These streets are analysed in detail in the Richmond Riverside Conservation Area Appraisal. The relationship between the Green and the Old Deer Park is also not readily apparent. A pair of large brick gate piers in the northern corner of the Green give access to a pedestrian route to the Old Deer Park, which crosses over the railway line before descending into the car park beside the A316, which includes part of the outer perimeter of the park.

Street Furniture

Paving and Hard Landscaping

Despite a relatively small area, there are an abundance of paving types evident throughout the CA, including historic stone setts, large stone pavers, and more contemporary repairs/upgrades completed in similar materials. Paving is primarily stone, and a variety of type and colours are presented, with a consisted neutral palette, and all are demonstrative of a high quality.

Lampposts

Lampposts within the Conservation Area are more decorative than the standard borough posts found in Central Richmond and beyond. The posts are black and topped with a Victorian inspired four-sided lantern supported by delicate tendrils. Near the top are two short projecting arms which can support hanging baskets or banners. Lighting has been upgraded to LED.

Bollards

There are a number of bollard designs evident within the Conservation Area, notably historic cast iron examples opposite Maids of Honour Row which have a square base rising into an octagonal top and are painted white with an IVWR and crown insignia. These are some of the earliest bollards in the Area and noted as being preserved, despite the removal of most other iron bollards to supply metals for WWII, due to their proximity to and contribution to the setting of Maids of Honour Row.

Other bollards in the immediate area replicate the design of these earlier examples but are instead constructed of concrete, including a group marked with IIER on the eastern corner. These are also placed around the green at points where the road narrows to slow the flow of traffic.

At the south corner of the Green, where the road curves close to Paved Court, there are a group of fluted bollards without precedence in the surrounding area. Despite a slightly more interesting design than simple smooth bollards found elsewhere in the borough, their use is inconsistent and lacks cohesion when considered the wider context of Richmond Town.

On the south-east side of the Green there are periodic placements of simple, standard bollards in black which are common throughout the borough. Despite their simplicity, they at least offer consistency with much wider usage and do not draw too much attention.

Bins

Bins within the Green are Green cylindrical bins within iron basket type supports, intended to blend with the green character of the area in longer views. Other bins are of a standard black jubilee style which is common throughout the borough.

6. Management Plan

Summary

The Appraisal has assessed the quality and the condition of the Richmond Green Conservation Area . Several site visits were undertaken between August 2022 and April 2023, when the area was observed and photographed.

This Appraisal has summarised the strengths and weaknesses of the area and this management plan will set out a strategy to consolidate and enhance these strengths with the aim of preventing erosion of the area’s special historic and architectural character.

The Conservation Area is well maintained, and it is hoped that this clearer, more extensively illustrated Appraisal will assist the Development Management process in making more informed planning decisions in respect of the Area’s character. It will also assist applicants to ensure their proposals contribute positively to the preservation or enhancement of the Conservation Area.

Under section 71 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 local planning authorities have a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of Conservation Areas in their area from time to time. Regularly reviewed appraisals, or shorter condition surveys, identifying threats and opportunities can be developed into a management plan that is specific to the Area’s needs.

Problems and Pressures

General

- Loss of traditional architectural features and materials due to unsympathetic alterations and extensions.

- Use of poor-quality products in building works such as uPVC, roofing felt and GRP (glass-reinforced plastic) products.

- Loss of front boundary definition, sometimes due to front garden parking to accommodate vehicles.

- Burglar alarms, poorly designed hanging signs, air conditioning equipment and various accoutrements add to the clutter and unsightliness of some shopfronts.

- The entire Conservation Area is dominated by parked cars.

Routes and spaces

- The small green space in front of Old Palace Terrace suffers from the dominance of parked cars and traffic as well as poorly maintained surfacing.

Buildings

- There is no longer any strong front boundary definition to 1-3 Little Green.

- Further encroachment into the gaps between Pembroke Villas and damage to front boundaries due to front garden car parking.

Eyesore sites

- The view along Quadrant Road to the rear of the shops is unattractive.

Opportunities for Enhancement and Recommendations

- Preservation, enhancement and reinstatement of architectural quality and unity.

- Resist new development outside the Green, which would be visible above the roof line of its perimeter buildings when viewed from within the Green.

- Encourage the reinstatement of appropriate walls, railings and hedges to boundaries throughout the Conservation Area. Also encourage improvement of existing boundaries where necessary.

- Coordination of colour and design and improvement in quality of street furniture and flooring.

- Ensure the visual gaps between Pembroke Villas are maintained and not encroached upon by further side extensions or other unsympathetic development.

- Encourage improvements in the design of front garden parking and boundary treatment and resist new applications for front garden car parking.

- Redesign the small urban square in front of Old Palace Terrace to reduce the dominance of traffic and parked cars.

- Use the existing ribbed bollard design should any further bollards be required on the Green.

- Keep open prospects of the Green free of signage as far as possible.

- Street scene general guidelines: existing areas of high-quality paving (such as stone and granite) should be maintained and extended if possible. Established patterns of street furniture should be continued or refer to the Council's Public Space Design Guide. Colour street furniture in black, and bollards and railings associated with the Green in white.

- Manage and maintain the quality trees and consider additional tree planting.

- The view along Quadrant Road to the rear of the shops is unattractive with negative impact exhibited by all the refuse facilities and plant and machinery for commercial premises on The Quadrant

Figure 49 Rear of Quadrant Road

Design Guidance

Historic England recommends that the Appraisal is also a source of guidance for applicants seeking to make changes that require planning permission, helping to make successful applications.

The guidance below will set out design guidance which encourages good quality of design, which will help to both preserve and enhance the Conservation Area.

Dwellings within the Conservation Area which are blocks of flats do not benefit from Permitted Development Rights, requiring planning permission to carry out alterations and extensions.

Windows

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace, so it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. In Georgian and early-mid Victorian terraces, each half of the sash was usually wider than it was high, but its division into six or more panes emphasised the window’s vertical proportions. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed a simpler pattern, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar. Casement windows are also common in later buildings. Warehouse buildings generally had darker frames with many panes of glass and used either timber or metal frames – often only a small section of the much larger window could open, wither by swivelling or in a casement style. These windows are a significant element of typical warehouse design and their retention integral for the legibility of the buildings historic use.

A high degree of original timber framed windows survive within the Conservation Area, and these make an important contribution to the special character and appearance. Where replacements have been required, these generally match the existing appearance and retain the buildings integrity. Replacements of a different style and materiality are unsympathetic to the historic appearance of the building and Conservation Area and can be disruptive to the harmony and rhythm of legible groups and create inconsistences within otherwise congruous terraces.

The quality of replacements can also vary, potentially diluting the consistent appearance of building groups, with some mimicking historic style while others employ inappropriate uPVC and casement windows. Common issues with replacement timber sashes include being of a poor quality, with thicker frames and higher reflectiveness, varied horn details, and a variety of glazing bar formats. Casement windows often have wider frames which create larger or overlapping gaps to their hinges, giving the impression of two windows rather than a single window in two parts.

It is encouraged that, in the first instance, original timber windows are retained and repaired. If replacement is required, all aspects of the window should be considered including opening type, glazing bar pattern, horns to sashes, and depth. New windows should be timber and are often best informed by surviving examples within the building or in the context of its setting. Timber frames are not only the most appropriate option, but a natural material which helps reduce the use of plastics , often found in other windows. Timber windows also have the benefit of being more cost effective, being much more durable and repairable than alternatives, and there are options to maintain their appearance while introducing energy saving and noise reducing features.

Single glazing is perhaps the most common window type. As such, simple like-for-like replacements would likely cause the least harmful impact on the existing appearance of a building and therefore the character and appearance of the area. Like-for-like replacements also benefit from being able to be carried out without the need for planning permission. Existing windows can often be improved through secondary glazing, where an additional glass layer is installed behind an existing window. Secondary glazing is an unobtrusive option to increase efficiency, reduce noise, and avoid intervention to existing fabric, often performing as well, and lasting longer than double glazing. This approach also often benefits from not needing planning permission.

Where appropriate and where there is justification for full replacement, slimline double and triple glazing with timber frames helps maintain a consistent appearance, while offering similar benefits to secondary glazing. Where double/triple glazing is accepted, black spacing bars and seals should be avoided – these should instead be white to blend with the frame. Trickle vents should be avoided or well concealed within the frame to maintain consistency with historic appearance.

Windows to contemporary development can vary in detail but it is still important to consider their design and proportions in relation to the character of the area.

Doors

Like windows, it is encouraged that residents, in the first instance, retain and repair any existing original timber doors. This is best for the environment, for the character and appearance of the area, and is often a more inexpensive solution than complete replacement. Simple modifications can often be carried out internally which improves the weatherproofing of the door without impacting its external appearance.

If a replacement is required, then it should match the original door for the property. Doors are typically simple timber four panel doors to Victorian buildings, and six panel doors to Georgian. Where decorative doors form an integral part of the character of an area or group, modern replacements or alternative designs will be resisted.

Existing styles of doors in the area generally manage to reflect the architectural style in which they are set, and original examples make a great contribution to the character of the area.

Roof Extensions

Roof extensions are uncommon and there is a consistency in scale within the area which contributes to its special character and appearance. Where limited roof alterations have occurred, these are sympathetic to the host building, as well as to the surrounding context in terms of scale and level of intervention. Rear dormers are generally employed given their small scale and ability to be well concealed from the public realm. Consistent roofscapes will not tolerate extension which erodes this consistency, nor will extensions which project above established and consistent building heights.

Gardens

Many properties in the area benefit from large gardens, and these make a positive contribution to the tranquil setting of houses and the Green, adding to the leafy verdant character of the Conservation Area. Full hard-surfaced frontages are generally uninviting and lessen the separation between the public and private realm, compromising the intended setting of the built environment. For these reasons, along with environmental and ecological reasons, they should be avoided.

Glimpsed views between houses to rear gardens and mature planting help break up the street scene and contribute to the overall green character.

Boundaries

Boundary treatments vary throughout the area but are generally well preserved, partly due to the high concentration of listed buildings. Boundaries are typically brick and match host dwellings, some complimented with greenery.

Painting and External Finishes

Painting is rare within the Conservation Area and introducing paint to additional properties will be resisted. Painting should only occur if the existing location has already been painted, and an appropriate colour should be selected to maintain the overall neutral palette of the Conservation Area – generally, only white has been used which mimics the occasional use of render.

External finishes are not a common feature to the Conservation Area as a whole, and the approach to their treatment is similar to paint – where existing finishes can be repaired and restored, and new finishes not normally approved. The predominant character of the area is derived from the consistent use of brick with some details and dressings in white render or contrasting brick.

Shopfronts and Signage

The number of shopfronts within the area is limited but the quality of shopfronts are generally good with many good surviving shopfronts or shopfront elements. Where historic elements survive, these should be retained and repaired in the first instance. Where traditional forms have been replicated or contemporary shopfronts inserted, these should continue to follow traditional designs should they need to be altered or replaced. Any new or replacement shopfronts proposed will need to maintain or improve the appearance of the existing shopfront or also follow these traditional designs as outlined by policies in the Local Plan, as well as in the Shopfronts Supplementary Planning Document.

Signage should replicate traditional styles with painted or applied letters to the fascia and simple hanging signs. Modern signage, including corporate branding, internally illuminated projecting box signs, and plastic / box fascia signs, will be resisted. Projecting signs should be of an appropriate scale and design, attached to the fascia or to the building in an unobtrusive manner. Where hanging signs are employed, these should use a traditional bracket and be of a simple design, as outlined in the Shopfront SPD.

Shopfront awnings were a common feature of historic shopfronts, and there are some examples of traditional awning styles sensitively reintroduced. Where appropriate, and where applied to traditionally styled shopfronts, awnings can add an attractive element and make a positive contribution to an active commercial streetscape. Awnings should be thoughtfully integrated into shopfront designs and positioned so that the other elements of the shopfront design are not impacted – typically set just below the fascia. Awnings of an overly modern design or material, or which contrast with the predominant palette of the area, may not be appropriate. Awnings to modern shopfronts are generally not appropriate.

Shopfront Security

Shopfront security can have an imposing impact on the appearance of the streetscape and create an uninviting atmosphere. For instance, projecting shutter boxes have a negative impact on the appearance of shopfronts and are not acceptable in Conservation Areas, nor are solid or perforated shutters. Instead, there are other systems which would be more suitable, and these are also outlined in the Shopfronts SPD and the Design Guidelines for Shopfronts Supplementary Planning Guidance.

Generally, shopfront security features are installed internally, which has benefited the appearance of the Conservation Area as a whole. For contemporary shopfronts, more passive security measures can be effective, such as laminated glass, which is not readily apparent and therefore mitigates security features from detracting from the appearance of the shopfront. Lattice brick-bond grilles can be installed internally behind the windows, with the box inserted into the ceiling – this prevents an external projecting box and the internal box from being visible through the shop window. This would allow for an appropriate level of security, while minimising the visual impact of shutters on the external appearance of the shopfront, and therefore on the Conservation Area. It also allows for passive observation by keeping the inside of the shop visible.

Energy Efficiency

Introducing energy efficient measures can reduce carbon emissions, fuel bills, and improve comfort levels. It is important that the appropriate course taken should be informed by the context of the building being improved, with each building having different opportunities and restrictions. Not all solutions will be appropriate across the Conservation Area, and the ‘Whole Building Approach’ advocated by Historic England encourages a case-by-case approach, which fundamentally considers the context, construction, and condition of a building to determine which solutions would be the most suitable and effective. More detailed advice can be found within the Guidance Note Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings: How to Improve Energy Efficiency 2018.

Solar Panels

Solar Panels and equivalent technology are most suitably placed on rear or side elevations where they are hidden from the public realm – principal elevations and roof slopes facing the public realm are less appropriate as they generally make the most substantial contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. New technologies, such as PV panels disguised as slates and sitting flush with roof materials, may be suitable in the appropriate context, and will be considered on a case-by-case basis.