Richmond Riverside

Conservation Area Appraisal

Conservation Area No.4

Figure 1 Drawing of Richmond Riverside, 1820s

Contents

- Introduction

- Statement of Significance

- Location and Setting

- Historical Development

- Architectural Quality and Built Form

- Management Plan

1. Introduction

Richmond Riverside Conservation Area is closely linked in terms of its history and development with two adjacent Conservation Areas - Richmond Green and Central Richmond– and this Appraisal Document should be considered in the context of the special relationship between them. The Appraisals for each Area can be viewed by clicking their respective names above.

Purpose of this document

The principal aims of conservation area appraisals are to:

- Describe the historic and architectural character and appearance of the area which will assist applicants in making successful planning applications and decision makers in assessing planning applications;

- Raise public interest and awareness of the special character of their area;

- Identify the positive features which should be conserved, as well as negative features which indicate scope for future enhancements.

This document has been produced using the guidance set out by Historic England in the 2019 publication titled Understanding Place: Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management, Historic England Advice Note 1 (Second Edition).

This document will be a material consideration when assessing planning applications.

What is a Conservation Area?

The statutory definition of a conservation area is an ‘area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’. The power to designate conservation areas is given to local authorities through the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservations Areas) Act, 1990 (Sections 69 to 78). Once designated, proposals within a conservation area become subject to local conservation policies set out in the Council’s Local Plan and national policies outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the London Plan. Our overarching duty, which is set out in the Act, is to preserve and/or enhance the historic or architectural character or appearance of the conservation area.

Conservation Areas SPD![]() (pdf, 653 KB)

(pdf, 653 KB)

Buildings of Townscape Merit

Buildings of Townscape Merit (BTMs) are buildings, groups of buildings or structures of historic or architectural interest, which are locally listed due to their considerable local importance. The policy, as outlined in the Council’s Local Plan, sets out a presumption against the demolition of BTMs unless structural evidence has been submitted by the applicant, and independently verified at the cost of the applicant. Locally specific guidance on design and character is set out in the Council’s Buildings of Townscape Merit Supplementary Planning Document (2015)![]() (pdf, 895 KB), which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

(pdf, 895 KB), which applicants are expected to follow for any alterations and extensions to existing BTMs, or for any replacement structures.

What is an Article 4 Direction?

An Article 4 Direction is made by the local planning authority. It restricts the scope of permitted development rights either in relation to a particular area or site, or a particular type of development anywhere in the authority's area. The Council has powers under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 to remove permitted development rights.

Article 4 Directions are used to remove national permitted development rights only in certain limited situations where it is necessary to protect local amenity or the wellbeing of an area. An Article 4 Direction does not prevent the development to which it applies, but instead requires that planning permission is first obtained from the Council for that development. View further information about Article 4 Directions to check if any permitted developments rights in relation to a particular area/site or type of development apply in your area.

Designation and Adoption Dates

Richmond Riverside Conservation Area was designated on the 14th January 1969.

It was subsequently extended on the 5th July 1977, 7th September 1982, and 7th November 2005.

Following approval from the Environment, Sustainability, Culture and Sports Committee on the 21st June 2022, a public consultation on the draft Appraisal was carried out between the 4th July and 1st September 2022.

This Appraisal was adopted on the 20th November 2023.

Map of Conservation Area

2. Statement of Significance

Richmond Riverside forms an important part of the historic settlement of Richmond, which has origins dating from the 14th century. The area is characterised by a mixture of development types, periods, and styles, most of which address or are associated with the Thames, ranging from robust, detached houses and villas with large gardens, to boathouses and workshops which remain actively used. There is a significant amount of public realm along the River allowing for its enjoyment and long views across and along the embankment are key to its character and appearance. The Conservation Area also includes important pieces of infrastructure, Richmond Bridge, Twickenham Bridge, Richmond Railway Bridge and Richmond Lock, which add visual interest and serve as local landmarks. Although less apparent than in adjacent Conservation Areas Richmond Central and Richmond Green, part of Richmond Riverside Conservation Area is built on the site of the former Richmond Palace, with potential for further archaeological evidence.

3. Location and Setting

General character and plan form, e.g. linear, compact, dense or dispersed; important views, landmarks, open spaces, uniformity.

Situated to the south west of London, Richmond lies between two significant areas of green space: The Old Deer Park/ Kew Gardens to the north and Richmond Park and Ham lands to the south. It is north east of Twickenham, north of Ham, south east of Isleworth, south west of Chiswick and west of Putney.

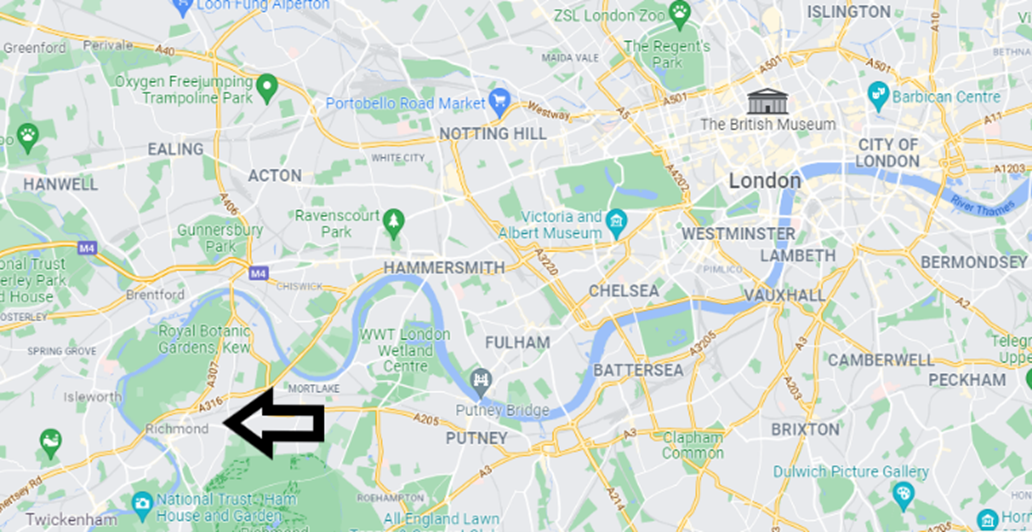

Figure 2 Aerial map showing Richmond in wider context

Figure 3 Map showing Richmond in wider context

The Conservation Area lies in the centre of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, and although it had its own distinct character, shares a relationship with both the Central Richmond Conservation Area, and the Richmond Green Conservation Area, and this context should be considered when studying any of the three.

Richmond Riverside Conservation Area lies to the west of Richmond Green and straddles both sides of the River Thames, running from Richmond Lock at its northern end to Richmond Bridge at the south, with Corporation Island in the centre. The riverside offers an iconic view; the eastern side is best known for its picturesque quality. The western bank is more residential in nature, with a mixture of residences and houseboats lining the river. Later extensions led to the inclusion of Park Road, a residential street running south from the Riverside.

Topography

Built into the banks of the Thames, both the east and west side of the Conservation Area gradually slope upwards away from the river, with the lower sections, particularly the towpaths, prone to flooding. The east side has a steeper incline, rising to the relatively flat area of Richmond Town centre, and this allows for longer and more varied views from within the Conservation Area toward the river.

Figure 4 Aerial view of Richmond Riverside

4. Historical Development

The history and development of the Conservation Area is fundamentally linked to the history and development of the adjacent Conservation Areas of Richmond Green and Central Richmond. As such, much of the information below is applicable to all three Areas, and it is valuable to consider these Appraisal documents concurrently with Richmond Riverside.

The growth of Richmond has been physically constrained by the large open spaces of Richmond Park and Petersham Common to the south and south-east, the River Thames to the west and the Old Deer Park to the north, later reinforced by the railway and A316 trunk road. Thus, throughout its development the town has only really been able to expand east and north-east.

The town’s history, and indeed its existence, is dominated by and defined by the medieval and Tudor royal manor and palace. It was not a medieval town as it was never granted a market or fair, and before 1501 it was known as Shene. The first record of the manor house of Shene was in the 12th century when it belonged to Henry I, who stayed there in 1126 and granted the manor to the Belet family. The settlement of Shene presumably gradually developed around the manor house and succeeding palaces but little is known of its role and layout. Given the regular visits by royalty, their courtiers and other high status visitors Richmond or Shene is unlikely to have been a typical medieval village.

The early medieval manor house was demolished by Richard II after the death of his Queen, and a new palace was built by Henry V &VI. After a fire in 1497 the palace was rebuilt by Henry VII, and from 1501, the village of Shene came to be known as Richmond, as Henry VII was the earl of Richmond in Yorkshire. The accession of the Stuarts saw the creation of the New Park (now the Old Deer Park) by James I from 1603 and Richmond Park by Charles I from 1634. The civil war and execution of Charles I in 1649 led to the sale and quick demolition of most of the palace, with Trumpeter’s House (1702-4), Old Court House, Wentworth House and Maids of Honour Row (1724-5) gradually being built on the site of the palace during the 18th century. However, The Gate House and associated walls and the Wardrobe survive.

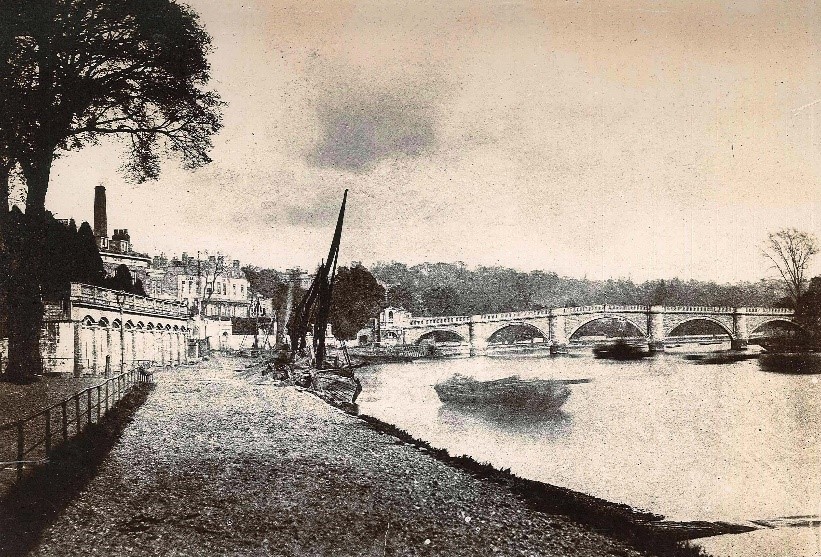

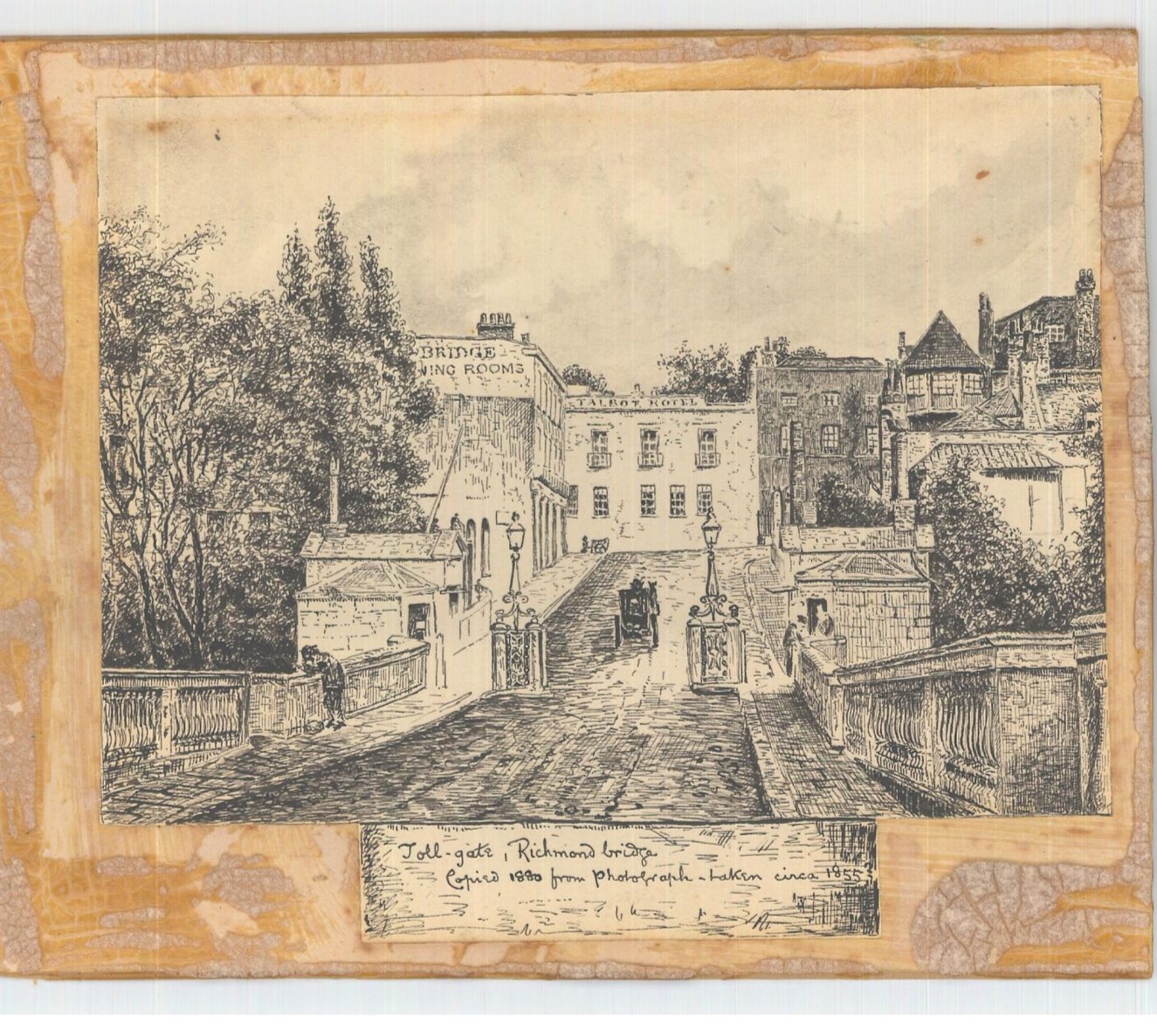

The village gradually developed into a town by the early 17th century due to the presence of the palace, and decline followed its demolition. Prosperity returned towards the end of the 17th century as Londoners fled the plague and the discovery of a spring led to Richmond becoming a popular spa town over the following century. Richmond Bridge, built in 1774-7, and the arrival of the railway in 1846 were key developments leading to the quadrupling of the population from 1810 to 1890, the impetus for growth leading to the loss of many of the original large houses and grounds for redevelopment. The arrival of the railway also led to a shift in river activity from agricultural and shipping to leisure, including the replacement of the river ferry with Richmond Bridge. As the area filled with wealthier inhabitants, the riverfront's importance as a place of leisure increased and included working boatyards to supply this demand.

Richmond Lock and footbridge opened in 1894. The popularity of the motor car saw a number of road improvements in the early 20th century, most notably the construction of the Great Chertsey Road and Twickenham Bridge (opened in 1933). The redevelopment of large houses continued, and notable buildings of the time include the Odeon cinema of 1930 and the railway station of 1937.

The Thames is a major contributor to activity in the area and today adds to an active daytime and night-time economy, housing a number of businesses including many bars and restaurants. Its association with leisure remains strong with public gardens and towpaths forming a popular destination for pedestrians, joggers, and cyclists. The Area is well connected to its surroundings, with the riverfront walkway providing access to residences, pubs, terraces, various greens, as well as multiple lanes and footpaths through Richmond. Much of the Riverside was restored in a neo-Georgian style by the architect Quinlan Terry from 1984–87.

Archaeology

The Conservation Area is partly within the Richmond Palace Archaeological Priority Area (APA), which also includes part of the adjacent Richmond Green Conservation Area, within which the above ground palace remains are located.

The APA covers the site and immediate environs of an early medieval manor house, and the site of a series of moated medieval palaces. Some Tudor buildings remain on site, while other elements and structural features of the Tudor palace were incorporated into the 17th to 18th century houses and residences that remain on site.

There is a history of positive archaeological interventions within the APA. It is classified as Tier 1 as it covers the site of an important Lancastrian and Tudor palace that played a significant role in the formation of the wider religious and royal landscape of Richmond.

Tier I is defined as an area which is known, or strongly suspected, to contain a heritage asset of national significance (a scheduled monument or equivalent); or is otherwise of very high archaeological sensitivity.

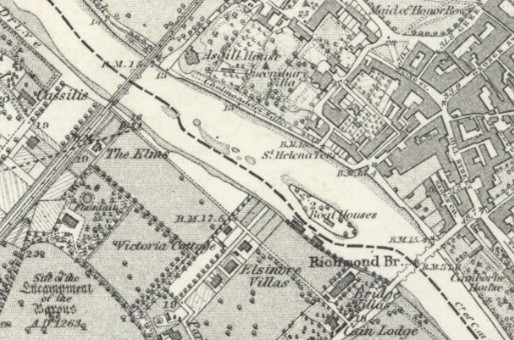

Figure 5 OS map, 1860s

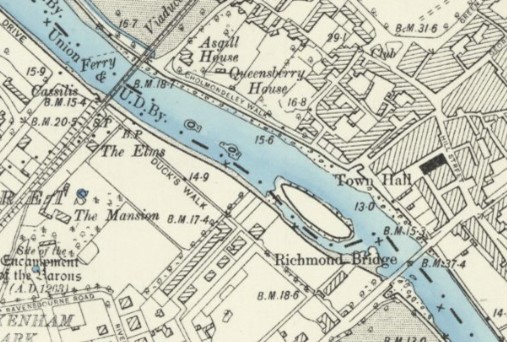

Figure 6 OS map, 1890s

Figure 7 OS map, 1910s

Figure 8 OS map, 1930s

Figure 9 Thames towpath, 1895

Figure 10 Richmond Riverside, c.1856

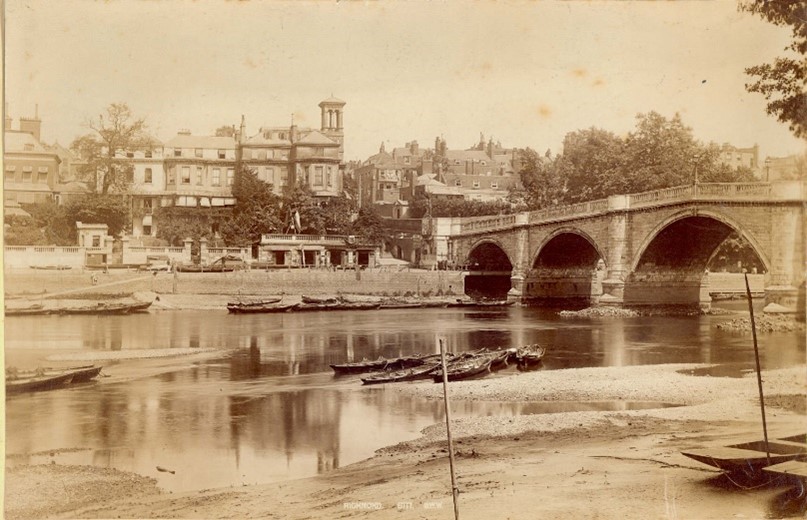

Figure 11 Richmond Bridge, c.1875

Figure 12 1880 Drawing of Tollgate on Richmond Bridge

Figure 13 1820 Drawing of Richmond Bridge

5. Architectural Quality and Built Form

Dominant architectural styles, the prevalent types and periods of buildings, their status and essential characteristics, and their relationship to the topography, street pattern and/or the skyline. Also important is their authenticity, distinctiveness and uniqueness of materials, design, form, texture, colour etc.)

Figure 14 Rear of buildings on Hill Street as viewed from Richmond Bridge

Figure 15 View of the Twickenham bank as viewed from Richmond Bridge

The Richmond Riverside Conservation Area covers both banks of the River Thames between Richmond Bridge and Twickenham Bridge and continues north to include the Richmond bank of the river up to and including Richmond Lock. The Conservation Area also includes Park Road on the Twickenham bank, and on the Richmond bank it extends to join the Richmond Green Conservation Area including Old Palace Lane. The river is a unifying element in the character of the Conservation Area, in which there are great variations in townscape character within short distances.

Figure 16 View of the River Thames and houseboats

The Conservation Area can be divided into three areas of similar character. Firstly, the area to the north of the railway line is accented by the three large engineering features of the railway bridge, Twickenham Bridge and the twin footbridges at Richmond Lock (all listed). These are the only dominant features in an area where both banks of the river have dense vegetation and are largely rural in character. Second is the Twickenham bank which has a semi-rural character, consisting of residential developments on the bank in a green setting and a plethora of house boats hugging the riverbank. Thirdly, the Richmond bank is characterised by a well-ordered urban townscape of fine buildings set on the rising bank in a formally landscaped setting. There is a distinct contrast between the urban character of the Richmond bank and the semi-rural character of the Twickenham bank, which is further emphasised by the vegetation on Corporation and the Flowerpot Islands.

Figure 17 View of the River Thames and Corporation Island

Spatial Analysis

Landscape, Landmarks and Vistas

From the Twickenham bank occasional views across to the Richmond bank from Ducks Walk and Willoughby Road are quite varied, ranging from views to the formal Richmond Riverside development, shorter and more intimate views to Corporation Island, to views to the more formal grounds of Trumpeters' House and Queensberry House. Views across to the Twickenham bank from Richmond Riverside are green and suburban in character.

Figure 18 Asgill House

Figure 19 Asgill House as viewed from Cholmondeley Walk

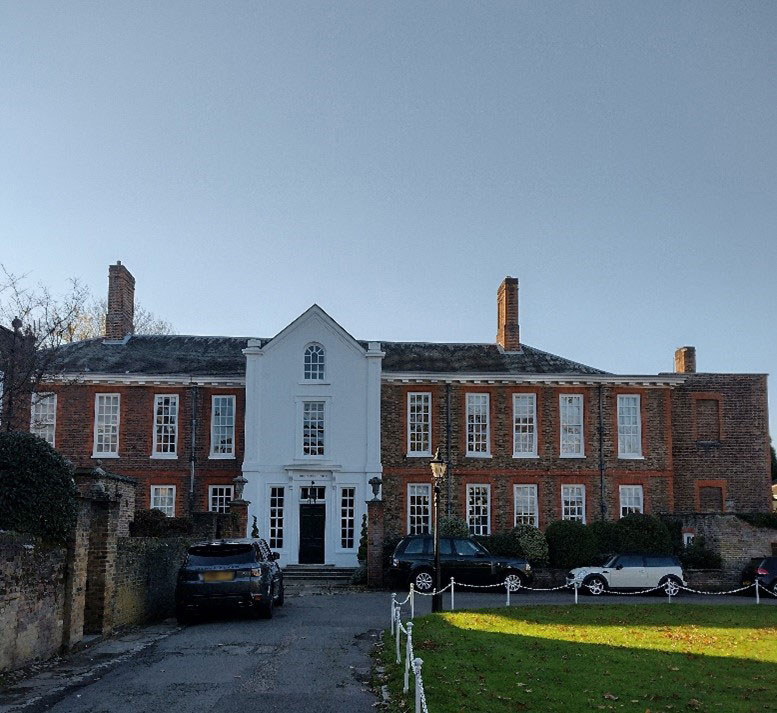

Framing the space at its northern end, adjacent to the railway bridge are Asgill House, listed Grade I, and The Elms, a Building of Townscape Merit. Asgill House was designed by Robert Taylor in 1767 as a weekend retreat for Sir Charles Asgill, Lord Mayor of London. It is an exuberant composition of three storeys stone faced with rusticated ground floor. These are freestanding buildings of high quality, prominent from both the towpath and the railway. The buildings act as gateways to the formal space of the riverside as viewed from the towpath but, more dramatically, as viewed from passing trains. The approaches to the bridge, tightly enclosed by vegetation, heighten the drama and surprise of the crossing and the two buildings frame the vista to the prominent Richmond Riverside development, Richmond Bridge and Richmond Hill beyond.

Richmond Bank

Richmond Bridge is the gateway to the town from the west. It allows many fine views and vistas of the river environment, both into the Conservation Area and south towards Richmond Hill. It provides a dramatic and high-quality image to the town. However, views from the bridge are dominated by the Richmond Riverside development of 1988 by Quinlan Terry. A formal and well maintained stepped riverside terrace in front of the development emphasises the river as an open space for popular enjoyment.

Figure 20 Richmond Riverside and rear view of buildings on Hill Street

Downstream from the Riverside development, the bank retains its urban character but takes on a more intimate scale at St. Helena Terrace as the buildings are domestic and set much closer to the river edge above a row of boathouses. Granite sett paving and the boat houses with their brick piers and arched entrances with timber doors and bottle balustrade parapet add to this character. However, the presence of cars detracts from the well-maintained riverside atmosphere. Motorised traffic at busy periods conflicts with the leisure uses, especially boat launching and use of the public houses by pedestrians. Beyond the boat houses the urban character gives way to a more open landscape, with a fully pedestrianised towpath leading north to Twickenham Bridge and Richmond Lock and Weir.

Figure 21 Boathouses, St. Helena Terrace

Figure 22 Thames towpath

Richmond Lock Area

North of Twickenham Bridge the character of the Conservation Area is strongly influenced by the proximity of the Old Deer Park. Almost continuous views into the park are possible from the towpath underneath the tree canopy lining the edge of the Park framed by obelisks. This part of the Conservation Area contrasts strongly with the more urban part to the south. From the lock are views looking north-westwards to the impressive façade and tower of Gordon House, a listed Grade II* private residence formerly used by Brunel University. The Lock, constructed in 1891, was designed by the engineer F.G.M. Stoney (1837-97) and is a local landmark. It is listed Grade II* and comprises two parallel 5 arched bridges of cast iron supported by stone piers with brick and stone lock houses at each end with elaborate ironwork to balustrades and lamps. Steps up to the bridge allow long views up and down stream.

Figure 23 View of the Twickenham bank

Twickenham Bank

Freestanding buildings in a well-treed setting define the character of the Twickenham bank. The scale of the buildings reduces away from Richmond Bridge. At the northern end the area takes on a less urban character and as Ducks Walk gradually approaches the river, a more intimate relationship exists here between pedestrians and the river, emphasised by the narrowness of the path, its enclosure by walls and vegetation and the occasional views possible of houseboats and the river beyond. The informal siting and variety of building style on the bank are also a key characteristic of this part of the Conservation Area.

Located along this stretch of the River Thames are Corporation Island and the Flowerpot islands, which collectively play an integral role in the riverside as they are feature in keys views and give a semi-rural ambiance to this part of the Conservation Area.

Corporation Island is a small island between Richmond Bridge and Richmond Railway Bridge. Formerly known as Richmond Ait, its current name appears to derive from its owners, the Corporation of Richmond, now the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It is uninhabited and there is no public access. The island is densely wooded with a range of tree species, that were planted in the 1960s after Richmond Borough Council felled the London Plane trees which had grown there. It is also home to a nesting colony of grey heron.

Just downstream from Corporation Island are the last islands on the Surrey stretch of the Thames, the Flowerpot Islands, which are two nearly circular islands covered in willows. Originally a single island, they were divided into two on the orders of the Duke of Queensbury in 1796 and subsequent tidal erosion has reduced them to the two tiny islets, or eyots.

Buildings and Architecture

Richmond Bank

Figure 24 Richmond Riverside

Riverfront

The Conservation Area contains a number of important listed and non-listed buildings set in a townscape of international renown. This is most apparent at Richmond Bridge, itself listed Grade I, dating from 1777 by James Paine & Kenton Couse (though subsequently widened in 1937). The bridge consists of five moulded segmental arches and constructed of Portland Stone. Richmond Bridge’s bicentenary was celebrated on 7 May 1977, and today is the oldest existing structure to cross the Thames in London. On the Richmond side of the bridge, there are business uses (e.g. café) in the converted arches beneath Richmond Bridge.

The construction of the Richmond Riverside development, completed in 1988, has helped integrate parts of the existing urban fabric comprising the listed buildings of the Palm Court Hotel and Heron House. The new development surrounding these buildings and the Town Hall emulates their grand Georgian and Victorian architectural style and the combination of existing and new build provides a rich tapestry of buildings that shape the urban space of the river frontage. The tiered urban space is popular with people for outdoor activities including alfresco eating and drinking.

Figure 25 View of Richmond Bridge

Figure 26 View of Richmond Bridge from Bridge House Gardens (the Gardens are in the neighbouring Conservation Area of Richmond Hill)

Figure 27 Boathouses next to Richmond Bridge

Figure 28 The White Cross public house

The tower of the former Palm Court Hotel, numerous cupolas on the development and the 1930 Art Deco front of the listed Odeon cinema emphasise the drama of the gateway to the town. Beyond the slipway, the remainder of the Riverside part of the towpath is dominated by the White Cross Hotel, St. Helena Terrace, St. Helena House and 1-3 Friars Lane. The scale of the buildings gradually decreases as one moves away from the bridge, but the presence of St. Helena Terrace is heightened by the visual effect of sitting above the ground-level boat sheds.

Figure 29 Trumpeters’ House

Beyond the built frontage the riverbank becomes Cholmondeley Walk and along this stretch are Queensberry House and Trumpeters' House. Queensberry House is an unusual and interesting composition of Classical, Edwardian and Arts and Crafts architectural elements. Dense vegetation prevents the full scale of the block being fully apparent from the river. Instead, interesting glimpses of the building and its gardens are possible as one walks along Cholmondeley Walk. This is in stark contrast with the powerful open vista of Trumpeters' House and its garden building directly facing the towpath. Clear views across the lawn are possible to the impressive frontage of this Grade I listed building; beyond Trumpeters' House, Asgill House marks the end of the formal 'town' part of the river front and stands out as an especially fine landmark building on the river front.

Lanes and Alleys

The narrow side streets leading from the town centre and Green to the riverside are an important element in the townscape, providing varied approaches to the river but with a common element of surprise. Street patterns and building arrangements between the town centre and river are very organic as the area has been developed and redeveloped over time. The area between Bridge Street and Water Lane has a far more urban character and is physically closer and better linked to the town centre.

Whittaker Avenue

Whittaker Avenue now forms part of the Richmond Riverside development. Views from the Avenue open up to the river, the bridge and the mansion blocks on the opposite bank. The listed war memorial forms a focal point at the end of Whittaker Avenue. The presence of parked cars by the war memorial can give a poor setting to views to it. The street is lined on both sides by large, impressive buildings. On the south side is the Old Town Hall and library of 1893 by W. J. Ancell, described by Pevsner as 'mixed renaissance' in style. The dramatically executed classical façade of the Riverside development provides a strong sense of enclosure and strengthens the contrast between the street and the open vista. Heron Square and Whittaker Place are internal courtyards, with an air of privacy and no shops or cafes.

Water Lane

Figure 30 Water Lane

The narrowness of the street and the tall buildings lining it on one side, in conjunction with the remaining warehouses at the river end, give Water Lane an industrial character at the lower end, while a surviving row of small houses from the original development of this street, in addition to some more recent small scale residential development and a public house, create a more residential character on the northern side of the upper end towards Hill Street. Granite setts and cart tracks reinforce the historic character though the poor state of repair of the adjacent forecourt, yellow lines, and block paving detract from the traditional quality street surface. The drop in ground level down to the river, the gentle curve of the street and the occasional changes in the building line are also essential elements of the character of the street. The curve of the street ensures a continually changing visual experience, Water Lane House becoming apparent only when nearly opposite it.

Of note are the warehouses at the bottom of the street; no. 18 is visible for most of the street's length, a good quality building which acts as a local landmark. The open space of the Thames Water tunnel entrance site and the smaller scale of the warehouse at no. 20 give a human scale to a small part of an otherwise large-scale formal townscape.

Friars Lane

This lane has the most diverse townscape character of those linking the town and river. There is a wide variety of building styles and scale, but views are predominantly of backs of buildings and flank walls. Buildings of note include Queensberry House, which has a busy and interesting elevation despite being the 'back' of the building. Incorporated into the boundary wall is a listed gazebo which appears as a small tower building sitting within the grounds of Queensberry House. A row of large mature trees in front are important in softening the contrast in scale with the listed Queensberry Place opposite. Friar’s Lane Car Park, which appears to be a well-utilised space for parking, is very poorly surfaced and jars with the residential character of the lane and surrounding properties. The workshops at the north end are an interesting group with their own distinct character. High walls and mature trees in the grounds of The Retreat give the area a sense of enclosure and seclusion.

Figure 31 Friars Lane

Figure 32 Friars Lane showing tidal flooding

Old Palace Lane

As one moves away from the town centre, the lane gradually changes from a distinctly urban character to one more rural, with a strong sense of enclosure due to its winding and narrow nature, its length and the large number of mature trees, particularly at each end of the lane. There is a varied palate of architectural styles to be appreciated, from red brick semis and terraces at the northern end to modestly scaled terraced cottages to the south. Before Old Palace Lane terminates at the river, there is Asgill House, a fine Palladian villa that stands on the site of the brewhouse of Richmond Palace. It was designed by Sir Robert Taylor and built in c1760 for Sir Charles Asgill, a wealthy banker, who was Lord Mayor of London in 1757-58, as a summer residence. From the late 1800s it was the home of James Hilditch, mayor of Richmond 1899-1900 and son of the painter George Hilditch. The house was sensitively restored in 1969-70, when the Victorian additions were removed. It is owned by the Crown Estate and Grade I listed.

Figure 33 6-8 Old Palace Lane

Figure 34 14-24 Old Palace Lane

Figure 35 The White Swan public house

At the north end of Old Palace Lane is one of two access lanes to Old Palace Yard, which is primarily characterised by tall boundary walls which lead to the yard itself. Old Palace Yard is a peaceful and secluded open space of high townscape and architectural quality which is primarily within the Richmond Green Conservation Area. On the south side of the Yard, within the Riverside Conservation Area, are the Trumpeter’s Inn (BTM) and Trumpeter’s House (Grade I), built on part of the former site of Richmond Palace. Trumpeter’s Inn has a forecourt which opens up the lane and contributes to a sense of openness with the Yard, and its smaller domestic scale and set back construction indicates its subservient nature and later construction. The more robust Trumpeter’s House is more grand in its appearance and encloses the Yard, but its primary elevation and deep front garden face the River, and thus its character is more closely tied to riverside development.

Twickenham Bank

It is only near Richmond Bridge and the railway bridge that there are any buildings of particular note. In Willoughby Road one encounters the two most important buildings in this part of the Conservation Area: Willoughby House (Grade II) with its slender campanile is a distinctive local landmark which originally faced directly onto the river frontage, and Richmond Bridge Mansions provide a high-quality townscape setting for the Bridge. It is now the strongest landmark building on the Twickenham bank, a dominant form viewed from Richmond Riverside. At the junction with Willoughby Road, Richmond Road widens out to give access to a slipway alongside the bridge. This creates a small open space of good townscape quality, trees either side providing enclosure before emerging onto the bridge.

Figure 37 Willoughby House

Willoughby Road and Ducks Walk are primarily pedestrian routes and form part of the riverside path between the railway bridge and Richmond Bridge. Most of the path is traffic free. Ducks Walk, with its large open setting, provides welcome views out to the river and its opposite bank, as a contrast to the enclosure of the footpath. Key characteristics of this part of the route include the semi-rural appearance of freestanding buildings on varying building lines in a very green setting, a variety in building styles and materials and a reduction in scale and height as one moves downstream.

Figure 38 Willoughby Road

Figure 39 Richmond Bridge Mansions

Figure 40 Richmond Bridge Mansions entrance

Figure 41 Ducks Walk

Figure 42 The Elms from Ducks Walk

From Ducks Walk the path takes on a far more secluded and enclosed character. Occasionally views are possible of houseboats and associated gardens, reinforcing the relationship with the river as it draws closer to the path. Just before the railway bridge the vegetation stops abruptly on the left, suddenly revealing a clear vista to the impressive facade of The Elms, framed by mature trees and rising slightly above the sunken garden. Original railings survive along the path but are partly obscured by the raised path and are in a poor state of repair.

Figure 43 Original railings of The Elms

Bridges

Figure 44 Richmond Railway Bridge

Figure 45 Detail of Richmond Railway Bridge

Beyond The Elms the path returns to the riverside and is dominated by the presence of the railway bridge and Twickenham Bridge. A focus for the space between them is the interesting hexagonal access shaft to a tunnel under the river used by the water authority. It is enclosed by railings and sits on an open area of green space. An identical structure sits directly opposite on the Richmond bank. The 1908 railway bridge is an impressive structure, similar in design to the footbridges at Richmond Lock and Barnes Railway Bridge. Restrained but elegant, its colour scheme fitting well with its surroundings; it includes a short viaduct of six well-proportioned and well detailed arches.

Figure 46 Tunnel access under river, Richmond bank

Figure 47 Tunnel access under river, Twickenham bank

Figure 48 Richmond Lock footbridge

The Richmond Lock footbridge, constructed in 1891, is more elegant and refined, designed by the engineer F.G.M. Stoney (1837-97) and forms a local landmark. It is listed Grade II* and comprises two parallel 5 arched bridges of cast iron supported by stone piers with brick and stone lock houses at each end with elaborate ironwork to balustrades and lamps. Full uninterrupted views of the bridge in its setting within this straight stretch of the river are possible from many points on the towpath.

Twickenham Bridge was constructed as part of the Great Chertsey Road project and completed in 1933 by Maxwell Ayrton. Now listed Grade II*, the bridge is distinctly interwar in design with Art Deco detail including decorative bronze cover plates that emphasise the three structural hinges of each arch. These hinges draw attention to the prominence of the bridge's technical virtuosity as the first large three-hinged concrete arch bridge to be built in the United Kingdom. The distinct design and materials of the bridge contrast strongly with the railway bridge and footbridges. Its sleek design of five arches (three of which are over the river), use of concrete and wide shallow spans reflects the confidence of the emerging new age of motoring and its connotations of speed; its monumental staircases, tall integrated lamp standards and bronze railings reinforce its presence in the riverside landscape.

Figure 49 Twickenham Bridge

Figure 50 Steps of Twickenham Bridge

Park Road

Park Road consists of many good examples of ornate and imposing Victorian houses, mainly two to three storeys in height and constructed of brick with canted bays to fronts and slate roofs. These are interspersed with a number of modern builds of varying materials, sizes and design. Many boundary walls have been lost to provide parking, weakening the boundary definition. In addition, some inappropriate replacement windows have been installed, which serve to dilute the character of the street. The street is well provided with trees, especially on the west side and north end, and the views along the street are terminated by mature trees to the north and by the flats at Old House Gardens to the south giving the street a sense of enclosure.

Figure 51 General view of Park Road

Figure 52 5 Park Road

Figure 53 Villa style houses on Park Road

Figure 54 Deniel Lodge, Park Road

Figure 55 16-24 Park Road

Townscape Details

Open Spaces, Trees & Soft Landscaping

The primary green public realm within the Conservation Area is Richmond Riverside Park on the east bank of the Thames. This formal arranged space is a stepped garden with abundant seating provided and offers sweeping views across the river as well as up and down stream. The space is very active with pedestrians and serves as a meeting point along the embankment. The majority of the park is laid to lawn with paved walkways. On the northwest side, a line of mature trees flanks a set of stone steps which lead to the Richmond War Memorial.

A less formal green space is also located on the east bank along the stretch of Cholmondeley W alk. This area essentially serves as a flood plain but offers a stretch of lawn along the towpath contributing to a countryside feel. The properties which front this area contribute to this character, with hedge lined boundaries and an abundance of mature planting within their large gardens. The west side of the path has been left to wild, which gives the impression of a country lane and presents a stretch of biodiverse landscape to the Area.

Similarly, to the west bank, although the area is private, deep front gardens and established plantings create a green landscape. Within the river itself, the three small islands covered in mature trees contribute to a strong verdant character.

Paving and Hard Landscaping

Despite a relatively small area, there are an abundance of paving types evident throughout the CA, ranging from more modern landscaping details within the public realm to more historic setts along historic routes such as Water Lane. Materials are primarily stone, and a variety of type and colours are presented, with a consistent neutral palette, and all are demonstrative of a high quality. There is a limited use of muted colour bricks in basket weave pattern.

Figure 56

Figure 58

Figure 60

Street Furniture

Lampposts

Lampposts within the Conservation Area are more decorative than the standard borough posts found in Central Richmond. The posts are black and topped with a Victorian inspired four-sided lantern supported by delicate tendrils. Near the top are two short projecting arms which can support hanging baskets or banners. Lighting has been upgraded to LED.

Bins

Bins are generally very simple paired litter and recycling in a rectangular unit are made of metal instead of plastic. As with most street furniture, they are black in colour, with gold lettering. There are a small number of ‘jubilee’ style plastic bins along the towpath which are standard throughout the borough.

Bollards

There is a mixture of bollards within the area including a group of historic bollards between Riverside and Cholmondeley Walk. Other bollards are generally of a simple standard design in black.

6. Management Strategy

Summary

The Appraisal has assessed the quality and the condition of the Richmond Riverside Conservation Area. Several site visits were undertaken between August 2022 and April 2023, when the area was observed and photographed.

This Appraisal has summarised the strengths and weaknesses of the area and this management plan will set out a strategy to consolidate and enhance these strengths and prevent erosion of the area’s special historic and architectural character.

The Conservation Area is well maintained, and it is hoped that this clearer, more extensively illustrated Appraisal will assist the Development Management process in making more informed planning decisions in respect of the Area’s character. It will also assist applicants to ensure their proposals contribute positively to the preservation or enhancement of the Conservation Area.

Under section 71 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 local planning authorities have a statutory duty to draw up and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of Conservation Areas in their area from time to time. Regularly reviewed appraisals, or shorter condition surveys, identifying threats and opportunities can be developed into a management plan that is specific to the Area’s needs.

Problems and Pressures

Routes and spaces

- The Thames Water area between the warehouse at 20 Water Lane and the White Cross Hotel is cluttered and untidy in appearance, and has a somewhat neglected feel.

- Friars Lane car park is rather stark in appearance.

Street furniture and materials

- The railings on the towpath between Richmond Bridge and Friars Lane are in a poor condition.

- The surface materials of Water Lane are in need of repair in many places.

- At the end of Water Lane, the slipway and its walls are in poor condition.

- Twickenham Bridge - in need of localised repairs and graffiti removal: loose stonework in places; a regular victim of graffiti.

Buildings

- Heron Square is lacking in active uses and pedestrian activity.

- Many of the boathouses at St. Helena Terrace are in need of repair.

- The condition of the facing brickwork on the railway viaduct is poor in many places.

- A number of properties in Park Road have suffered from unsympathetic minor alterations, especially removal of boundary walls for car parking.

Eyesore sites

- The walls and surface of the slipway at the bottom of Water Lane are in a poor state of repair.

- The above-mentioned area outside the White Cross Hotel and Thames Water site at the end of Water Lane is cluttered and unsightly.

Figure 56 Riverside view with railings and cobbles

Figure 57 Water Lane slipway, with tarmac in poor condition

Figure 58 Abundance of bins and clutter between 20 Water Lane and the White Cross Hotel

Opportunities for Enhancement and Recommendations

- Preservation, enhancement and reinstatement of architectural quality and unity that is preferably based upon historic evidence.

- Seek to encourage good quality and proportionate design and better-quality materials that are sympathetic to the period and style of the building.

- Continue improvements to paving and street furniture throughout the Conservation Area. Paving and street furniture changes should accord with the guidance in the Council's Public Space Design Guide.

- Encourage the reinstatement of appropriate walls, railings and hedges to boundaries throughout the Conservation Area, with specific attention to Park Road. Also encourage improvement of existing boundaries where necessary.

- Carry out maintenance to the Water Lane slipway surface and walls.

- Encourage the repair, restoration and use of the boathouses at St. Helena Terrace to match those beside Richmond Bridge.

- Investigate the potential for removing parked cars in front of St. Helena Terrace to improve conditions for pedestrians and allow the removal of yellow lines.

- Simplify the cluttered area between the White Cross Hotel and Thames Water site at the end of Water Lane.

- Water Lane: pursue paving improvements with the retention of the existing granite setts.

- Friars Lane car park: surfacing and landscape improvements to Friars Lane car park.

- Protect key views, such as to Trumpeters’ House.

- Maintenance of Twickenham Bridge - consolidation of stonework and metalwork and cleaning of graffiti when necessary.

- Riverside design guidance to be developed in accordance with the Council's Urban Design Study and Thames Landscape Strategy.

- Street scene general guidelines: existing areas of high-quality paving (such as stone and granite) should be maintained and extended if possible. Established patterns of street furniture should be continued or refer to the Council's Public Space Design Guide. Colour street furniture generally black.

Design Guidance

Historic England recommends that the Appraisal is also a source of guidance for applicants seeking to make changes that require planning permission, helping to make successful applications.

The guidance below will set out design guidance which encourages good quality of design, which will help to both preserve and enhance the Conservation Area.

Dwellings within the Conservation Area which are blocks of flats do not benefit from Permitted Development Rights, requiring planning permission to carry out alterations and extensions.

Windows

Windows make a substantial contribution to the appearance of an individual building and can enhance or interrupt the unity of a terrace, so it is important that a single pattern of glazing bars should be retained within any uniform composition. Generally, windows follow standard patterns/styles. In Georgian and early-mid Victorian terraces, each half of the sash was usually wider than it was high, but its division into six or more panes emphasised the window’s vertical proportions. Later Victorian and Edwardian buildings often employed a simpler pattern, with the top and bottom sash either having one large pane, or a single central glazing bar. Casement windows are also common in later buildings. Warehouse buildings generally had darker frames with many panes of glass and used either timber or metal frames – often only a small section of the much larger window could open, wither by swivelling or in a casement style. These windows are a significant element of typical warehouse design and their retention integral for the legibility of the buildings historic use.

A high degree of original timber framed windows survive within the Conservation Area, and these make an important contribution to the special character and appearance. Where replacements have been required, these generally match the existing appearance and retain the buildings integrity. Replacements of a different style and materiality can be unsympathetic to the historic appearance of the building and Conservation Area and can be disruptive to the harmony and rhythm of legible groups and create inconsistences within otherwise congruous terraces.

The quality of replacements can also vary, potentially diluting the consistent appearance of building groups, with some mimicking historic style while others employ inappropriate uPVC and casement windows. Common issues with replacement timber sashes include being of a poor quality, with thicker frames and higher reflectiveness, varied horn details, and a variety of glazing bar formats. Casement windows often have wider frames which create larger or overlapping gaps to their hinges, giving the impression of two windows rather than a single window in two parts.

It is encouraged that, in the first instance, original timber windows are retained and repaired. If replacement is required, all aspects of the window should be considered including opening type, glazing bar pattern, horns to sashes, and depth. New windows should be timber and are often best informed by surviving examples within the building or in the context of its setting. Timber frames are not only the most appropriate option, but a natural material which helps reduce the use of plastics, often found in other windows. Timber windows also have the benefit of being more cost effective, being much more durable and repairable than alternatives, and there are options to maintain their appearance while introducing energy saving and noise reducing features.

Single glazing is perhaps the most common window type. As such, simple like-for-like replacements would likely cause the least harmful impact on the existing appearance of a building and therefore the character and appearance of the area. Like-for-like replacements also benefit from being able to be carried out without the need for planning permission. Existing windows can often be improved through secondary glazing, where an additional glass layer is installed behind an existing window. Secondary glazing is an unobtrusive option to increase efficiency, reduce noise, and avoid intervention to existing fabric, often performing as well, and lasting longer than double glazing. This approach also often benefits from not needing planning permission. Where appropriate and where there is justification for full replacement, slimline double and triple glazing with timber frames helps maintain a consistent appearance, while offering similar benefits to secondary glazing. Where double/triple glazing is accepted, black spacing bars and seals should be avoided – these should instead be white to blend with the frame. Trickle vents should be avoided or well concealed within the frame to maintain consistency with historic appearance.

Windows to contemporary development can vary in detail but it is still important to consider their design and proportions in relation to the character of the area.

Doors

Like windows, it is encouraged that residents, in the first instance, retain and repair any existing original timber doors. This is best for the environment, for the character and appearance of the area, and is often a more inexpensive solution than complete replacement. Simple modifications can often be carried out internally which improves the weatherproofing of the door without impacting its external appearance. If a replacement is required, it should match the original door for the property in style and materiality. Doors are typically simple timber four panel doors to Victorian buildings, and six panel doors to Georgian. Where decorative doors form an integral part of the character of an area or group, modern replacements or alternative designs will be resisted. Existing styles of doors in the area generally manage to reflect the architectural style in which they are set, and original examples make a great contribution to the character of the area.

Roof Extensions

Roof extensions are uncommon and there is a consistency in scale within the area which contributes to its special character and appearance. Where limited roof alterations have occurred, these are sympathetic to the host building, as well as to the surrounding context in terms of scale and level of intervention. Rear dormers are generally employed given their small scale and ability to be well concealed from the public realm. Consistent roofscapes can be harmfully impacted by extension where the uniformity is broken. This is also the case for extensions which project above established and consistent building heights.

Gardens

Several properties in the area benefit from large gardens, many of which have river frontages. These make a positive contribution to the landscape setting of houses, adding to the leafy verdant character of the Conservation Area. Full hard-surfaced frontages are generally uninviting and lessen the separation between the public and private realm, compromising the intended setting of the built environment. For these reasons, along with environmental and ecological reasons, they should be avoided.

Boundaries

Boundary treatments vary throughout the area and include a mix of brick, timber, and natural options such as hedging or other planting, often a mixture of different elements, particularly to residential properties. This variety gives a more informal, rustic appearance, and overly formal and robust boundaries would not suite the character of the area.

Painting and External Finishes

Painting is rare within the Conservation Area and introducing paint to unpainted properties will be resisted. Painting should only occur if the existing location has already been painted, and an appropriate colour should be selected to maintain the overall neutral palette of the Conservation Area.

External finishes are not a common feature to the Conservation Area as a whole, and the approach to their treatment is similar to paint – where existing finishes can be repaired and restored, and new finishes not normally approved. The predominant character of the area is derived from the consistent use of brick with some details and dressings in white render and red brick.

Shopfronts and Signage

There are a limited number of shopfronts within the Conservation Area and most commercial premises are generally pubs and restaurants, which often employ many of the same elements of traditional shopfronts in their design. The quality of these premises are a good quality with many good surviving historic elements. Should alterations be proposed, these should be retained and repaired in the first instance. Any new or replacement shopfronts proposed will need to maintain or improve the appearance of the existing shopfront or also follow these traditional designs as outlined by policies in the Local Plan, as well as the, the Shopfronts Supplementary Planning Document.

Signage should replicate traditional styles with painted or applied letters to the fascia and simple hanging signs. Modern signage, including corporate branding, internally illuminated projecting box signs, and plastic / box fascia signs, will be resisted. Projecting signs should be of an appropriate scale and design, attached to the fascia or to the building in an unobtrusive manner. Where hanging signs are employed, these should use a traditional bracket and be of a simple design, as outlined in the Shopfronts SPD.

Shopfront Security

Shopfront security can have an imposing impact on the appearance of the streetscape and create an uninviting atmosphere. For instance, projecting shutter boxes have a negative impact on the appearance of shopfronts and are not acceptable in Conservation Areas, nor are solid or perforated shutters. Instead, there are other systems which would be more suitable, and these are also outlined in the Shopfronts SPD and the Design Guidelines for Shopfront Security Supplementary Planning Guidance.

Generally, shopfront security features are installed internally, which has benefited the appearance of the Conservation Area as a whole. For contemporary shopfronts, more passive security measures can be effective, such as laminated glass, which is not readily apparent and therefore mitigates security features from detracting from the appearance of the shopfront. Lattice brick-bond grilles can be installed internally behind the windows, with the box inserted into the ceiling – this prevents an external projecting box and the internal box from being visible through the shop window. This would allow for an appropriate level of security, while minimising the visual impact of shutters on the external appearance of the shopfront, and therefore on the Conservation Area. It also allows for passive observation by keeping the inside of the shop visible.

Energy Efficiency

Introducing energy efficient measures can reduce carbon emissions, fuel bills, and improve comfort levels. It is important that the appropriate course taken should be informed by the context of the building being improved, with each building having different opportunities and restrictions. Not all solutions will be appropriate across the Conservation Area, and the ‘Whole Building Approach’ advocated by Historic England encourages a case-by-case approach, which fundamentally considers the context, construction, and condition of a building to determine which solutions would be the most suitable and effective. More detailed advice can be found within the Guidance Note Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings: How to Improve Energy Efficiency 2018.

Solar Panels

Solar Panels and equivalent technology are most suitably placed on rear or side elevations where they are hidden from the public realm – principal elevations and roof slopes facing the public realm are less appropriate as they generally make the most substantial contribution to the character and appearance of the Conservation Area. New technologies, such as PV panels disguised as slates and sitting flush with roof materials, may be suitable in the appropriate context, and will be considered on a case-by-case basis